On November 13th, I was all set to see the Toubab Krewe play the B.Side Lounge in Boulder. I headed downtown early, hoping to catch the band after sound check. I'd been corresponding back and forth with their tour manager for a few weeks, and after agreeing to review the band's new album, Live at the Orange Peel (due to be released on Nov. 24), I managed to score an interview with guitarist Drew Heller. The details, however, had only been worked out that morning, and I wasn't terribly surprised to find no one waiting for me back stage at the B.Side. Fortunately I had a few cell phone numbers on hand, and after getting no response on Drew's, I called up the tour manager directly.

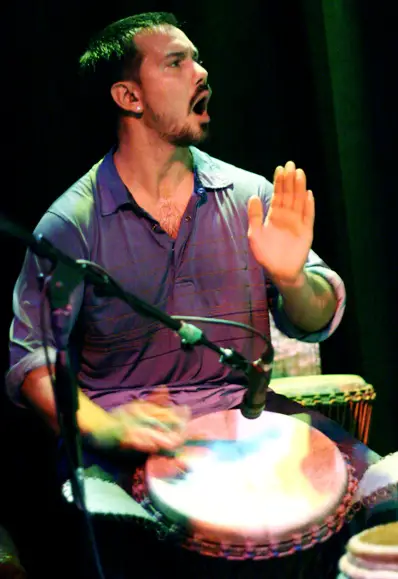

"We're down the street at Hapa," he said "Do you know where that is?" Yeah, I said, and told him I'd be right down. Actually, he'd said Kasa, but it's amazing how the two words sound almost identical over a jittery cell phone connection. The two words are also the names of two sushi restaurants only a few blocks apart, making it all the more confusing. Long story short, I figured everything out and before long I was sitting down with strings player Justin Perkins, and percussionist Luke Quaranta.

"Sorry about Drew, he is one of the hardest guys to get a hold of because he never answers the phone," Luke said.

"I've known Drew forever, and to this day he never picks up his phone," Justin laughed. "When we were kids, I'd used to call him up at his folks' house, and they'd tell me to call him right back on the upstairs line, and I'd be like 'you're sure he's gonna pick up?' They'd say of course, but it would still take like ten phone calls before he'd pick up the phone!"

GW: How long have you been playing music together?

JP: As the Toubab Krewe? Since late 2004, beginning of 2005.

GW: You guys knew each other for a while before that though?

JP: Yeah, Drew and I have known each other since we were four or five, and have been playing music together since we were seven or eight. Teal (drummer) was also from North Carolina, we met him in middle school, and started playing together in high school, playing a little bit of drums.

GW: Luke, you were born in New York though, right?

LQ: Yeah.

GW: How did you find yourself down in North Carolina?

LQ: Well I went to Warren Wilson College in 1997. Teal also started at Warren Wilson in '97, and we joined a percussion group on campus that was already formed. Then just kinda really got into West African drumming and fell in love with it. The group began to grow and we decided to travel to Guinea in 1999 to Conakry and that started us on a path to going back and forth to West Africa over the next ten years. In 2001, Justin and Drew were also playing with Common Ground and we came together and traveled there with like 14 people, 7 drummers and 7 dancers. Like he said, they'd been playing together for years in a number of different bands and while they were over there they got more into the melodic kind of styles and traditions whereas we had been more into just the drumming side of things. Drew started at Warren Wilson in 1998, and Jutin spent quite a bit of time at the College, so that was sort of a hub for the interest in the West African thing, and for traveling back and forth to Africa.

GW: When you guys were playing together way back, what kind of music were you playing back then?

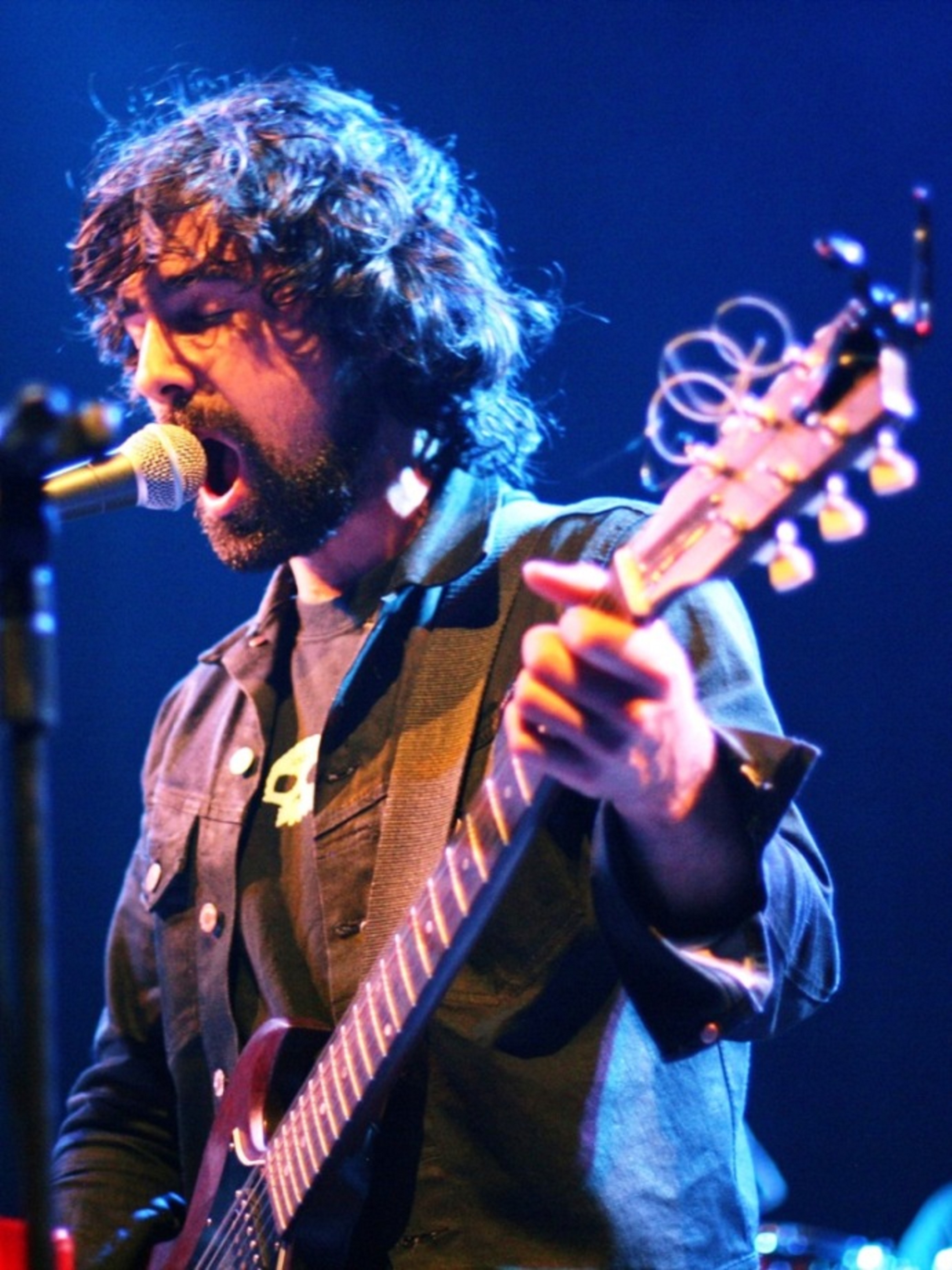

JP: Oh man, well I was playing drum set, Drew was playing guitar, and we had bass players with us too sometimes. Everything from Led Zeppelin to Pantera and Jimi Hendrix and whatever. Rock and roll. I guess I started studying drum set with a teacher when I was about 10 or 11, and he (Drew) got me into Latino music, Afro-Cuban stuff, so that was my first foray into ethnic percussion I guess, if you wanna call it that. American music for the most part, but it gradually shifted as we got older.

GW: At this point in your career, how would you describe the music you make, maybe to someone who had never heard it before?

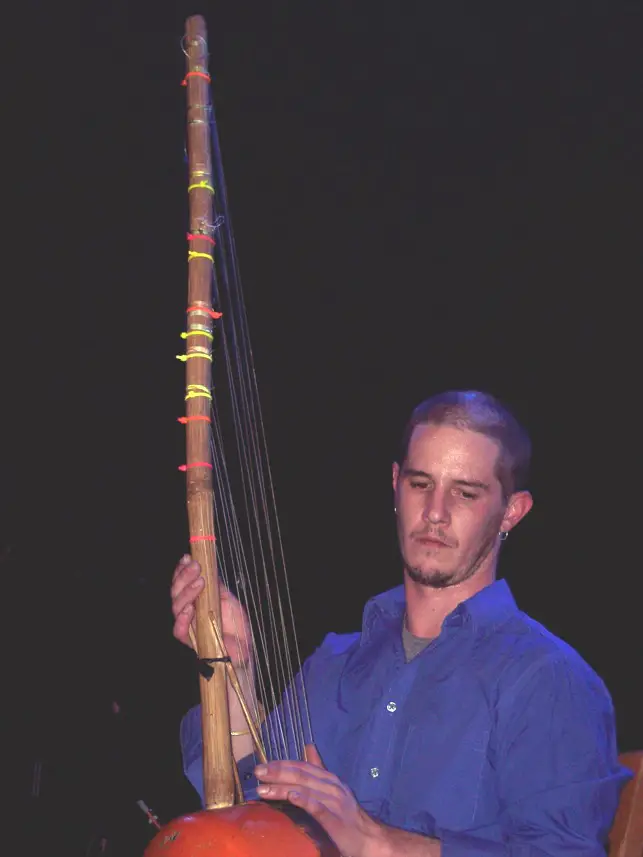

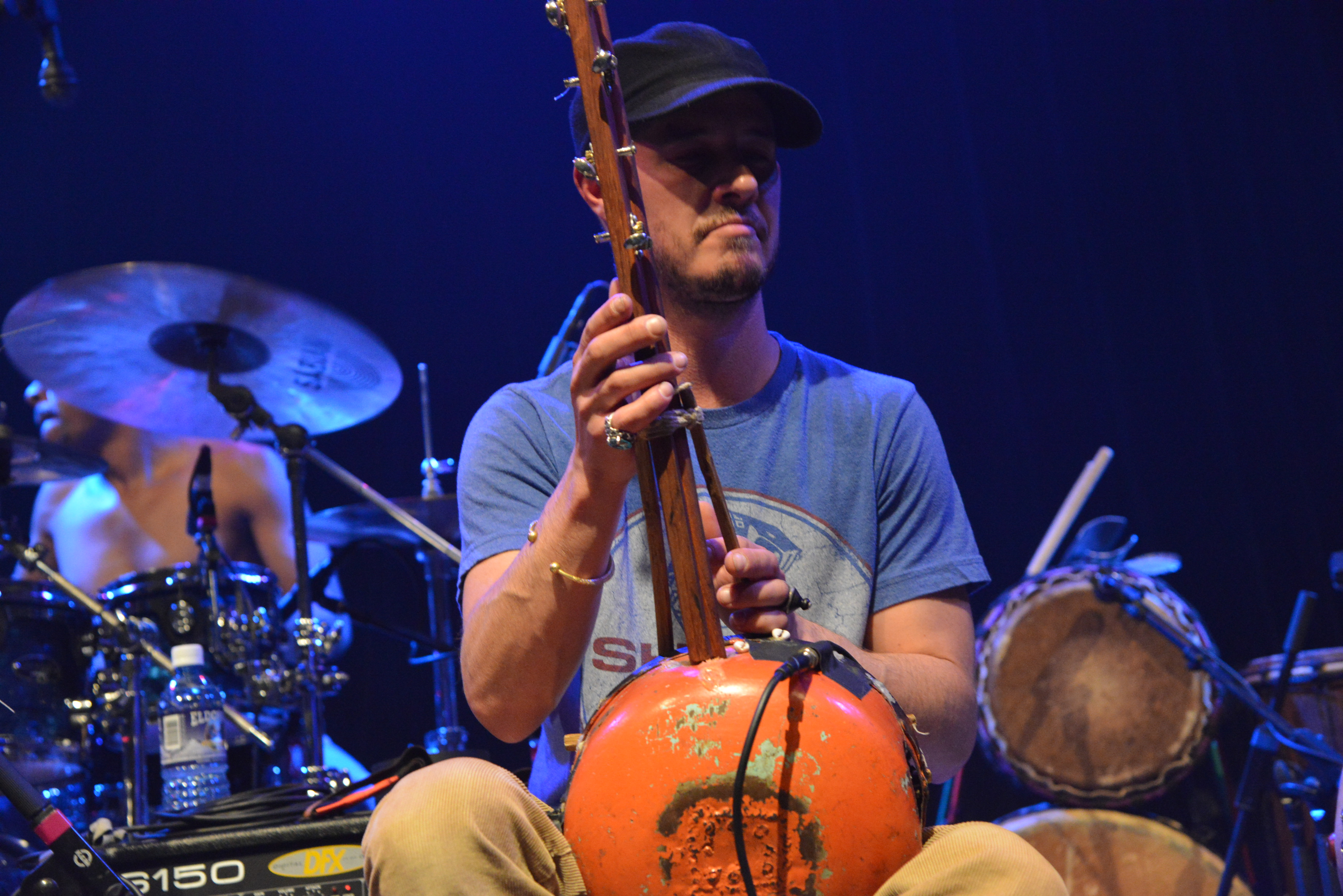

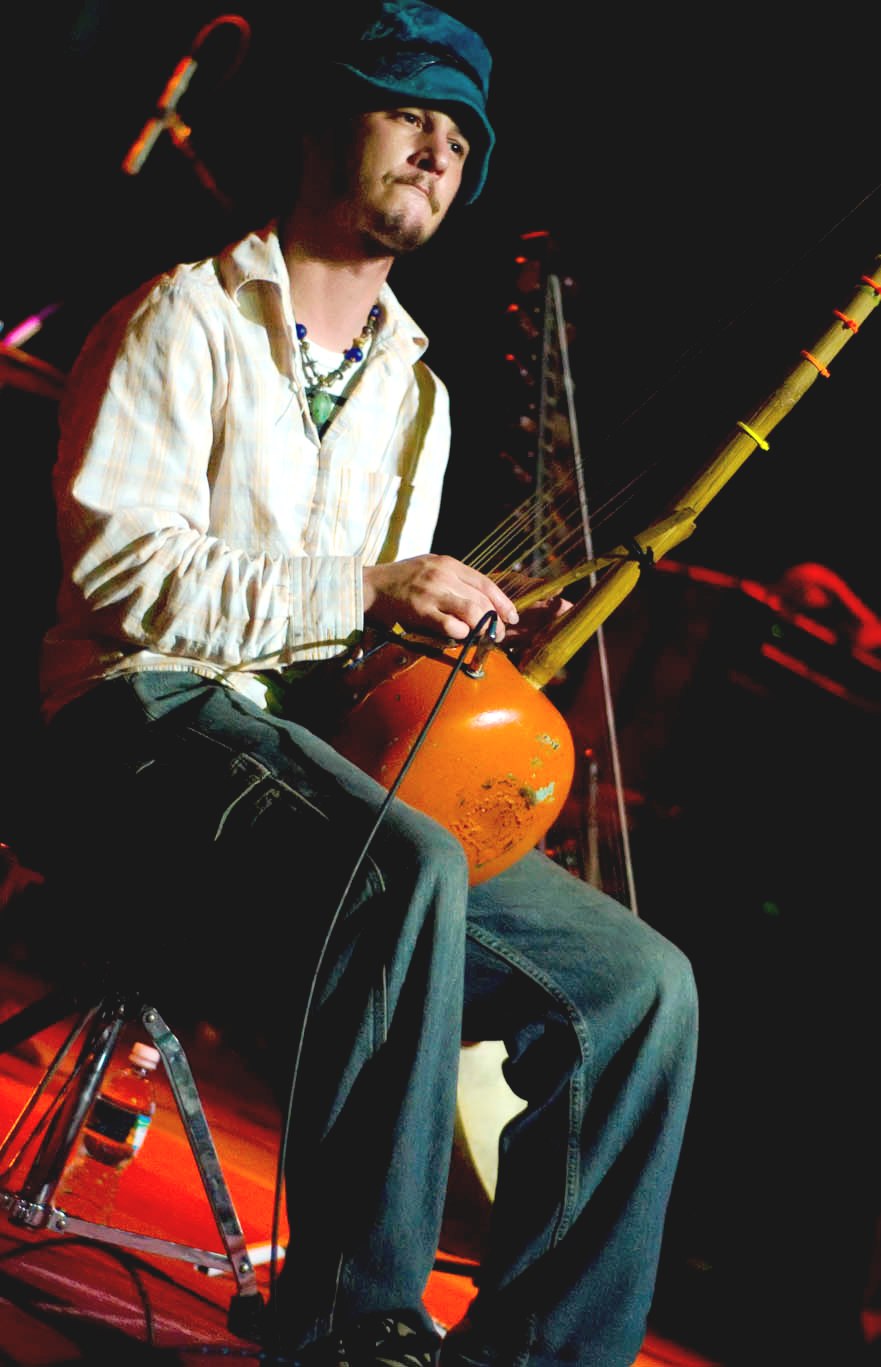

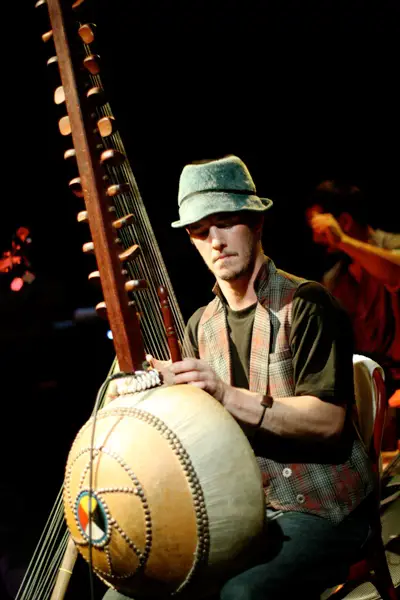

LQ: I dunno, it's hard. People throw out a lot stuff. We used to call it Afro-cowboy-ninja-surf music because its obviously heavily African and it's got that country thing going on because of where we're from and everything, at least these guys and myself, our second home being in the mountains. So there's that twang, and even that mountain music thing going on. And then the ninja thing, that really came from Justin's ngoni teacher Via (???), who was a total virtuoso and really transformed the way the kamale ngoni is played. And if you saw him play, it was like there was a kind of ninja quality to it, almost a supernatural quality. Even to this day we like to pull up the videos, and his teacher, who tragically passed away a couple years ago, he was really, really amazing, and got Justin on the path with the kamale ngoni which is really rare in terms of its style. Then the whole surf thing, well there's a lot of surf aspects to it too. These guys were playing a lot of gypsy stuff, gypsy swing music, at one point, and Django Reinhardt is a big influence for Drew, our guitar player, and Junior Brown, and Dick Dale, so there's a good bit of surf guitar styles in there.

JP: There's a lot of stuff that makes its way in there. It's kinda been something that we don't necessarily have the intention of doing, and it's not something that's spoken about, but any influence that can make its way in, it usually does.

GW: Difficult to peg in any case.

JP: Yeah, it is, because it really encompasses a lot of stuff.

LQ: It's instrumental, I guess. I think instrumental is probably the biggest category it could fit in, I mean not having vocals, you put yourself in a pretty distinct musical camp.

JP: World Music, too, if you wanna call it that, it could be World Music.

GW: Given how many different styles there are in there, do you find that you resist being pegged in any certain way?

JP: It's easy to be pegged sometimes, but it's fun because there are no words, so you can interpret it any way you want to. And you can call it whatever you want to.

LQ: And people have come up some really cool ways to describe it, too. Like the Village Voice, lately my favorite thing their calling it is "a futuristic, psychedelic, neo-grio frenzy." That was cool, because psychedelic is fucking cool, and that's definitely in there for sure. Futuristic is just a complement. And then the neo-Griot thing…

JP: Griots are the musicians in West Africa, among the Malinké people, the Manding people. There's a caste system over there, so the French term is Griot, what they call themselves Jeli. My teacher, who was Jeli, he's into 33 generations of what he does, and that gets passed on father to son, father to son, mother to daughter, mother to daughter.

LQ: And for them to say "neo-Griot" like we're bringing traditions to a whole different group of people, that might not be exposed to them other than through a group of Americans who are doing this. And there's a lot of traditional music in what we do, you know, so that's cool.

GW: That is cool. About the continual trips back and forth to West Africa, how important is it to you to keep going back there to touch base, or get back to your roots maybe.

JP: Oh man, it's like going to school every time you go over there, and you get drilled. And it's so good, and you go over to get your chops up. We play here constantly, all year long, just playing, playing, playing. And you get better along the way, but when you get to go sit down with your teacher, be on the porch and have intensive studies for weeks, months at a time, it's just continuing an education I guess.

LQ: Yeah, it's important, definitely.

JP: And culturally too, to leave America and go to a place like that, that's just the exact polar opposite of this country. It's good on all levels.

GW: It was last year when you played out at the Festival of the Desert in Mali, and its supposed to be the world's most remote music festival. What was that like?

JP: Very surreal. You have to go to Timbuktu in Mali – you've heard of Timbuktu before, not that anyone knows where that is, but it really does exist, in Northern Mali on the southern fringes of the Sahara – so you've got to get to Timbuktu first, then take a five hour ride up through the desert to this oasis called Essakane, which is where the thing is held, and its just, well, I don't know how to describe it really.

LQ: I mean, we flew into Timbuktu in a crazy, like, 60's era, Russian…

JP: Ghetto-ass plane, with wires everywhere.

LQ: And then we get there, and get off the plane and these people stick microphones in our faces and we do an impromptu interview right there on the tarmac. And the Timbuktu airport is like one very small building. Then we got in a jeep with like a professional desert driver or something, and start going through the desert. It's underbrush and stuff, and we got stuck like four or five times, because somehow we ended up with the four wheel drive vehicle that, um…

JP: It only had had two wheel drive (laughs)!

LQ: Yeah, two wheel drive. So literally we out in the middle of this desert pushing this jeep, it was crazy. And finally, three or four hours in, the underbrush kind of vanished and we got into these rolling sand dunes, like what you would think of as the Sahara. The sky and the sand were almost the same color, like the horizon was really obscure. And camel skin tents everywhere, and Tuaregs, and other ethnic groups too, but Tuareg is the main ethnic group. And they're totally wrapped in scarves, and long, very flowy outfits, on camels with these really elaborate, uh, whatcha call it…

JP: Saddles.

LQ: Saddles, yes, crazy elaborate. Amazing, artistic saddles, and jewelry…

JP: The Tuaregs, they're the ones who put the festival on, and they're nomads up in the desert. They travel with their caravans of camels between Mauritania, Western Sahara, Mali, Algeria, Lybia, Niger, Chad. They trade a lot in salt, and in gold, they make the most beautiful jewelry in the world. We met some guys, this one in particular – we're sitting in our tent one day, just chillin' and this guys rolls by and sits down and shows us his jewelry. So we struck up a conversation, just kickin' it, and he'd been traveling for like 52 days from the north, with a pack of like 25 camels just to come down to this festival by himself.

LQ: It's a major gathering, and not just music, but culturally too. It started during the peace process between the north and south of Mali, there was a lot of conflict, and the north doesn't get as many resources from the Malian government.

JP: But that's where all the resources are, lots of gold, lots of salt, lots of oil that their starting to tap into. So the Tuaregs, they're not black Africans, they're a different ethnic group. They don't speak the same language, or have the same customs. But you get down to southern Mali where the government is, they're black Africans. And so, the Tuaregs aren't getting any money from any of this stuff, and they've fought for a long time to have a separate state.

LQ: Was it '95ish when the peace process started?

JP: No, like '91, I think, they took a bunch of arms, and set a huge fire to three or four thousand weapons, and there was a truce, and people started working together, but they've started fighting again lately.

LQ: But they started the festival around that process, and all these great musicians from the south come up to the north, so it's like a real big social gathering. It's pretty important and people come from all over. At this point a lot of Europeans and a few Americans, we were like one of two American groups I think. And then also to see all the people that we admire, who have become some of our favorite artists in the world. Like Tinarawin, who helps put on the festival, they're a big group up there. They actually started playing electric guitars, and came up with this psychedelic desert rock music, and now they've toured the states and put out a couple really successful albums, but it's pretty wild.

JP: They met in refugee camps in Algeria, while the fighting was going on.

LQ: So they're a pretty radical group.

GW: Did you get a bit of culture shock when you came back here after being involved in something like all that?

JP: That's when it really sets in. I mean, you get it a bit when you first get there just because it is so different, but when you stay there for a couple months at a time, and come back here, it's like, wow! And when you see two places like these that exist simultaneously, just the discrepancy in how people live, and people's values, and what they think is important, it blows your mind.

GW: So back to you're work in the States, you guys are about to release a new album, and are selling it at shows now. And it's a live album. What was the motivation behind doing a live album as opposed to a studio album?

JP: Well we got into the studio last fall, and had been touring a lot. We got off the road, and literally had like two days off, then went into the studio, and when you're used to being on stage like 200 nights a year, and you go into a studio environment, where you're all separated, and everything is pinpoint perfect, it's a bit of an adjustment. It's hard to feel like you're capturing that energy that you're used to every night.

LQ: And I think we realized that in the process of coming off the road, and going into the studio for short periods of time, and trying to capture on record what we'd been playing live – what happened was, we had a couple sessions that we were getting ready to record on the album, then we recorded the Orange Peel show, and after listening to both things, the vibe and the energy really came across more so than in the live setting than in the studio. So I think it also taught us that in the future, we're looking forward to going into the studio for a month or six weeks, like most people do, rather than going in for 10 days and trying to cut a record. But going in for six weeks and allowing that whole process to be it's own thing, writing in the studio and allow the live arrangements to change and adapt. So the Orange Peel thing turned out so great. It was the close of the year, and we had some awesome guests, so we just decided to go with that, you know. And we're such a live band, and haven't given ourselves the opportunity to really develop the whole studio aesthetic, so we went with the live stuff instead. We've gotten a lot of good feedback, and I think it's a cool record, and I look forward to getting in the studio for another project.

GW: The official CD release party is later this month back in Ashville, is that the big show you're really looking forward to?

JP: Yeah, it's always fun to go home, and be in front of friends and family, people who have supported you since you started doing it.

GW: And just throw a party.

JP: Oh, yeah, it's a total party!

LQ: And it's crazy too because you're always in motion, you know? At least the way we've been touring, it's constant motion, and you don't always see how you're growing because you're always moving. And sometimes, you'll realize it all in a moment, for example going back to the Orange Peel, you're going home after, well we've been on the road for almost three months now, and you get onstage and you finally land where you started. You're whole community is in front of you and you're like, damn. It just pulls everything into perspective, like the way you might have grown personally or grown as a band.

JP: Especially in Asheville since we only get to play there once a year, so the last time we played there was New Years when we recorded. It's fun to go back and share that.

LQ: And to see how the music has grown. And we've got a lot of new music too, even beyond what's on the record, which is cool, so we're looking forward to sharing that!

* * * * *

After saying my goodbyes, I checked my phone on the way out, and saw that Drew Heller had sent me a text message. "Sorry I missed you at B.Side," it read, "if you have any follow up questions or want to chat after you guys get through, I'm all about it." Why not, I thought. Problem is, I had asked all the best questions I had planned out already. I decided to wing it, and headed back up the street to the B.Side. I sent a text back to Drew, "on my way over to B.Side now, where are you?"

A few seconds later, "Sushi Zanmai, just finishing now, will meet you out front."

"Wanna go get a coffee or something?" Drew asked after we introduced ourselves. Sure, I said, it's going to be a long night, might as well have some caffeine. So we walked down to the Pearl Street Mall, to the Bookend Café, arriving at the last possible minute before they shut the doors for the night. Over two shots of espresso, Drew told me about how he got into music in the first place.

DH: It's been around me my whole life. My parents are both musicians, and my dad works in music. He's a composer, and music producer, and recording engineer, and what not. So since birth, there's always been a music studio around, and musicians, and bands, mostly in the acoustic scene, but there were electric bands too. I remember when I was in 4th grade there was a local Asheville band that was around a lot. They were working on a record, and were kinda like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, kinda like funky rock and stuff. That's one of the main rock bands I remember, but for the most part more along the lines of traditional Appalachian music, old time music, like Doc Watson and David Holt, a lot of story tellers…

… It was really in 4th grade when I got really into it, I got an electric guitar the summer before 4th grade. There had been guitars around the house, acoustic guitars, and I'd been playing piano since I was a little kid, my parent got me piano lessons when I was in 2nd grade, or something like that. Although I didn't make it past Mary Had a Little Lamb, I grew up always playing piano, just making stuff up, kind of a homegrown technique, or not technique whatever it is, and was very into that. I still love to play piano. Getting an electric guitar, I don't know. At that time in 4th grade, I was very influenced by my older brother's and my older sister's music collection before getting really influenced by my parents music, which was always around. But my older brother Rory's a big Led Zeppelin Fan, he had all the Led Zeppelin tapes, and Guns and Roses were real heavy at that time, so that was pretty influential…

…For my birthday, I was in 6th grade, I got this double disc Jimi Hendrix set from a family member, and it completely flipped everything. I had been really into music and into playing, but there was an emotional turning point there, hearing that. I was very into Jimi Hendrix, and still, to the day I die, I will love Jimi Hendrix and am very connected to that.

Drew spoke at length about the growth of his personal musicality, laying out a long list of influences, including NWA, Easy-E, Good Old Boys, Nirvana, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Fatala, and Django Reinhardt

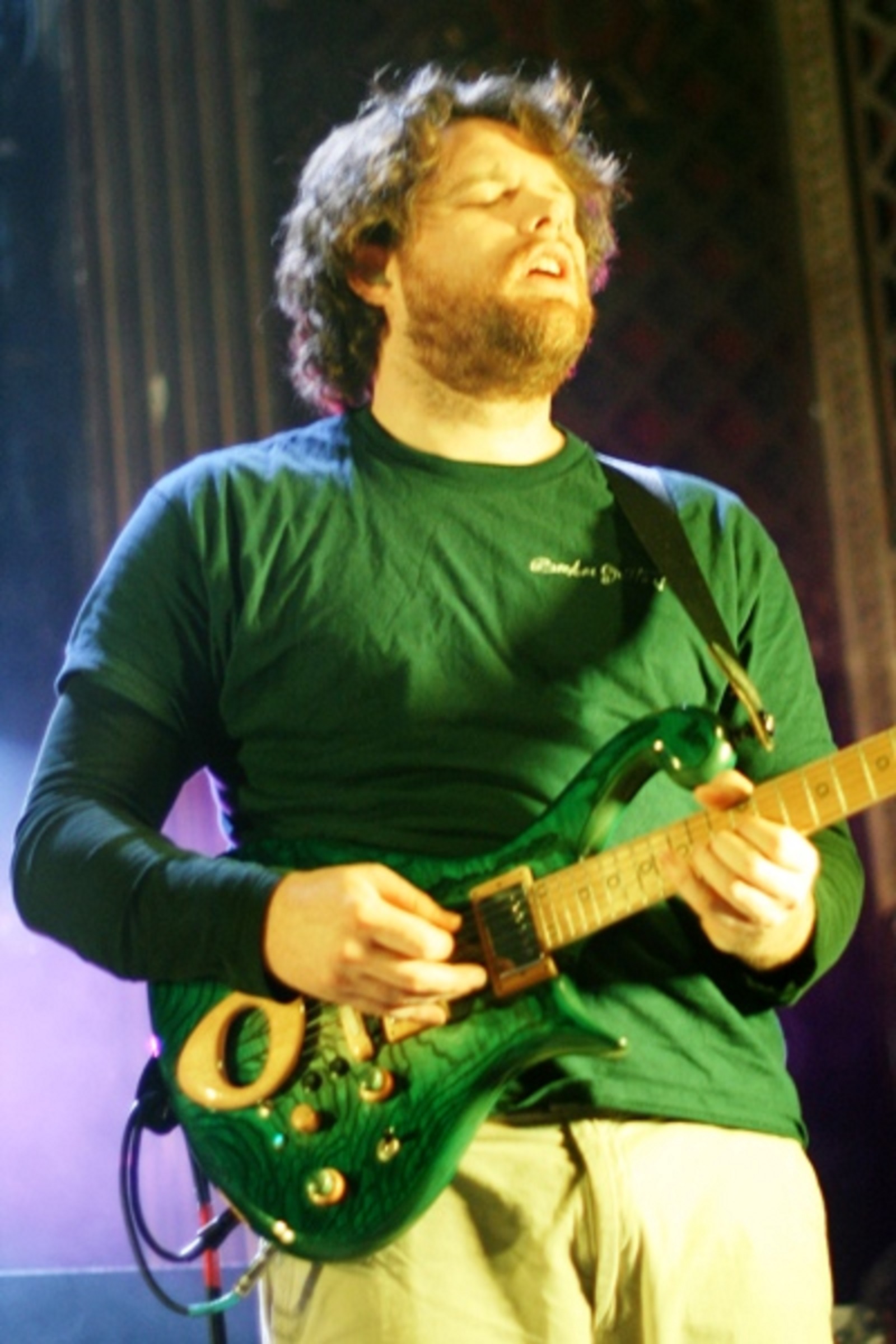

DH: Justin and I had been in bands throughout late elementary school and middle school. And we took it seriously; we rocked out all the time in the basement. In 9th grade we had this project that involved 4 of us. We'd been playing trios, all instrumental, and so we had this crazy basement band called the Blistent Mer, or, actually we called it the Mercury Blues Project - it didn't really have a name, we only played one show, which was at a crazy party, it was wild. That was the first time that, I dunno, things were opening up. There was mind expansion, there was music, and old worlds were dissolving and new ones forming. That was definitely a turning point as far as really knowing that it was something I really loved doing, and knew I would be in love with forever.

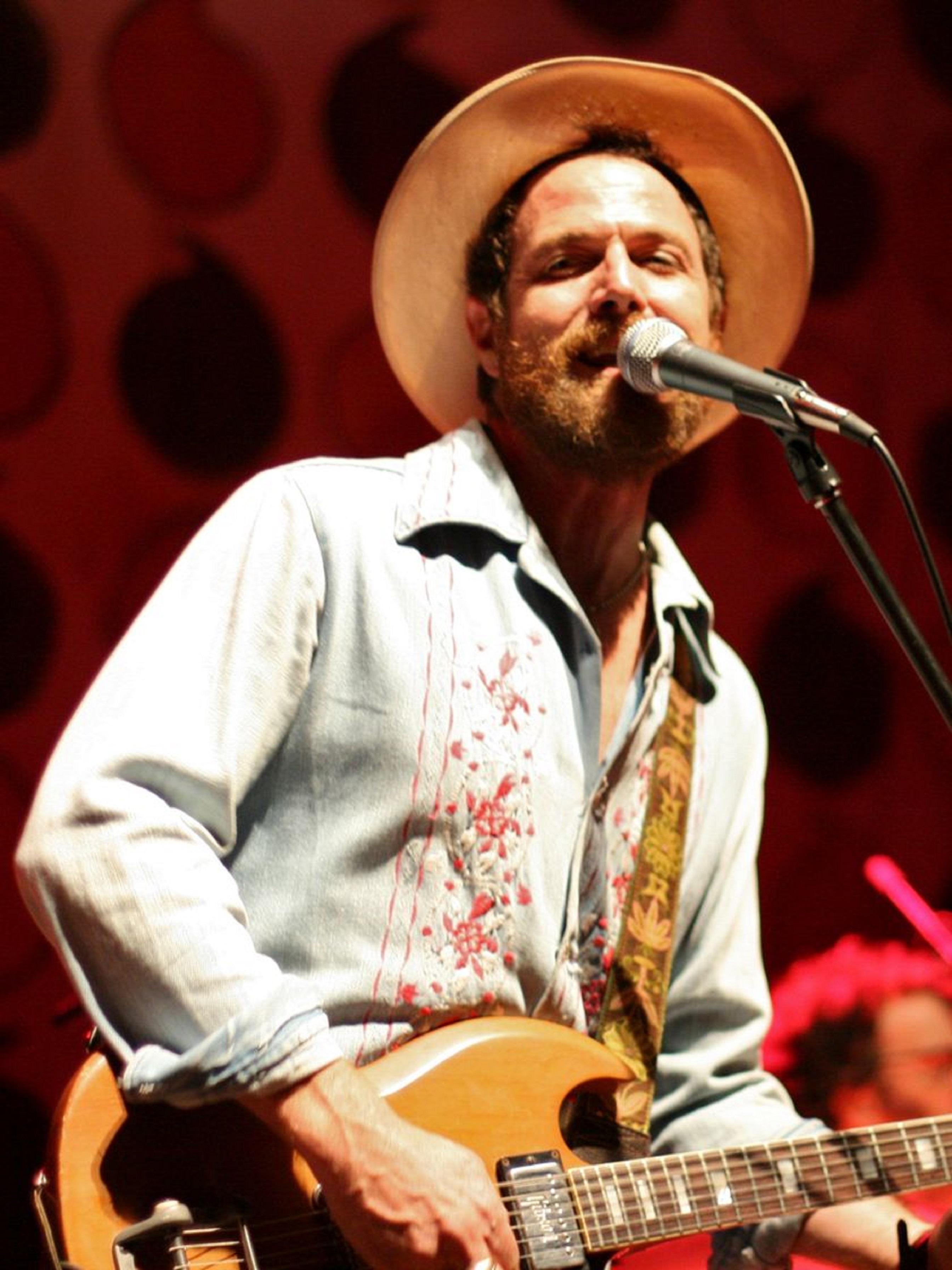

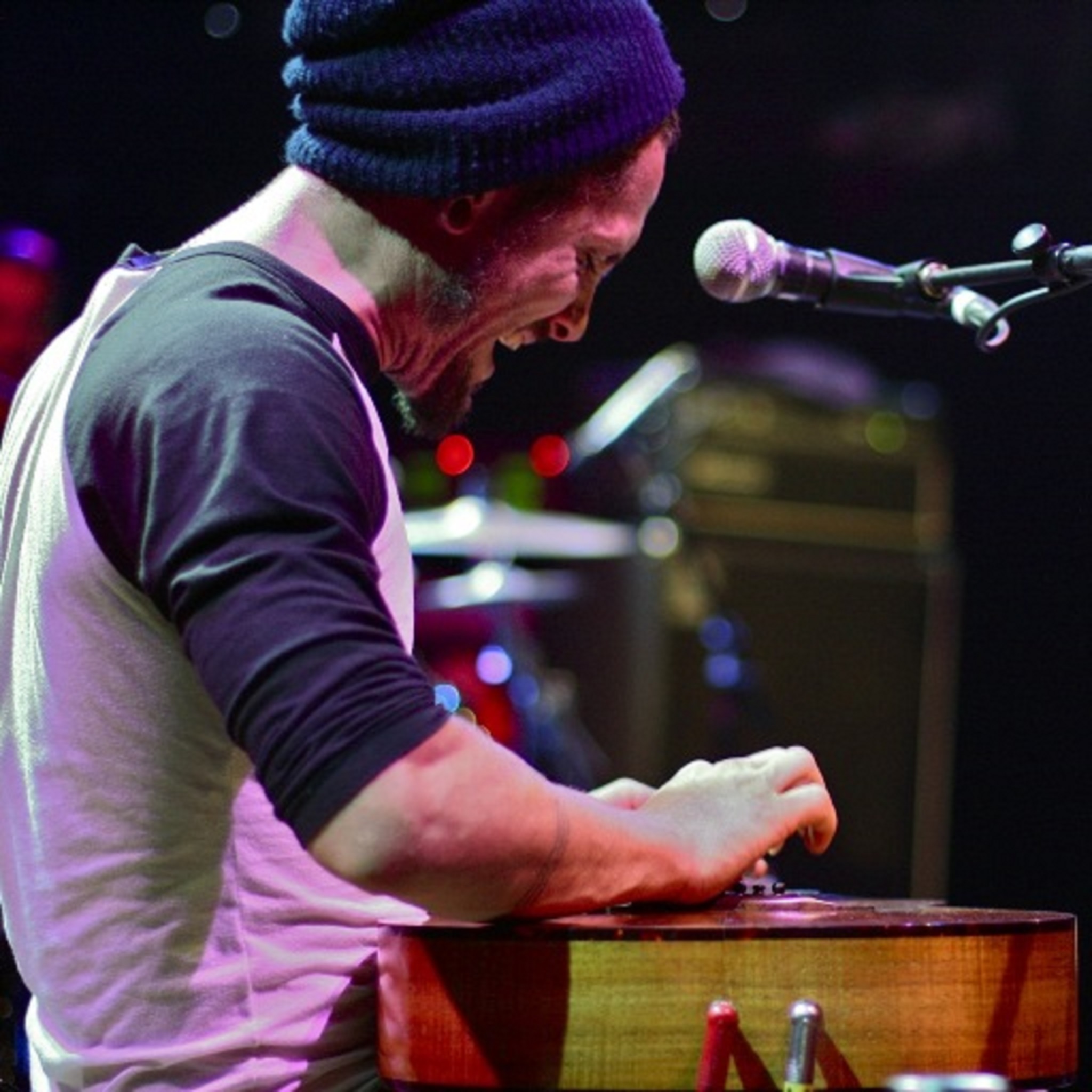

GW: At this point, the guitar is your primary instrument.

DH: Yeah.

GW: You mentioned this other band from Guinea, who played electric guitar and drums, but the guitar is not necessarily something I associate with the West African sound music. When you were starting to get into that vein, and starting to do the West African inspired stuff, how did you approach that on the guitar?

DH: I feel grateful that I had a good bit of time before traveling to West Africa to get into the more traditional side of things. I feel like the traditional scene gave me a decent sense of discipline in terms of wanting to learn the way something is played. I've known from the start with my parents guidance that there's no one right way to play anything or do anything really, but that it's worth trying to go after whatever it is you are trying to do. I had been exposed mainly to the percussion through a man named Gordon Ray, who Justin may have mentioned, who was a drum builder from Asheville who would host drum circles and bring in teachers from West Africa. He was the one who exposed us to percussion from Guinea, and the National Ballet of Guinea, which has lots of percussion, 4 or 5 djembe players, lots of doum-doums, kekeni, balaphone, and kora, so I'd heard the balaphone and kora, but really aside from Fatala hadn't heard the guitar realm of West African music. So I brought a guitar to West Africa on the first trip in 2001, because I didn't want to stop playing guitar – it was between college semesters and I didn't want to spend a whole summer without a guitar.

I'm going to study kora and balaphone, that was kind of what was in my mind. Then I was just entirely floored by the guitar culture there. It took about two weeks to realize, partially because I was in a language void, and it was hard to go out much. I spent the first couple of weeks there studying kora and balaphone all day, and going on some trips into the neighborhood and what not. I saw one guitar in Guinea, one wedding, I remember on that first trip, and there was an electric guitar just cranked, playing so loud. It was playing traditional music, but it hit like rock and roll.

Then we went to Abidjan in the Ivory Coast, and got to start going out a lot and hearing that side of things. Very quickly there we met a man named Lamine Soumano who is an amazing guitarist and kora player, her really plays everything.

GW: I'm not gonna know how to spell any of these names!

DH: That's fine, I can email them to you (and he did!). Lamine was right away a great teacher. That trip I was in the dark with language. I couldn't speak any French, and definitely couldn't speak anyone's first languages which were Susu, Malinké, and Jula, which is a variation of Bambara. That's another lifelong goal there, learning those languages. So I was spending time with Lamine with just the language of music, back and forth, but he's an amazing teacher, we hit it off really well, and he definitely was able to communicate a lot of very important things on that trip. Most importantly, which I know I'll always carry, just that the accompaniments, and the traditional roots of things, its important to play those correctly, or at least to learn them correctly before you do your own thing with them, but no one can tell you how to solo. He would do something, I would be like 'Oh, that, how do you do that?' And he's like 'I'm just soloing.' So I'd say 'well, can you teach me some soloing?' and he said 'No, I've heard you, you can play. So play from your heart, play what you would play.' That was so liberating, to hear that from such an amazing spirit that I happened to be connecting with. It shook everything up in that way, with the way I was feeling about playing traditional music. I had the realization that all my pedantic, 'I have to do it right, I have to do it a certain way so that it's authentic' ideas, and that whole idea that things have to be authentic were the chains holding me, and they were unshackled right there. My influences are, I dunno, Southern Appalachia, or twangy or country or rock and roll, and I shouldn't hold those back, because there are no boundaries in the music.

We talked for a while longer, about Live at the Orange Peel, which Drew is very proud of, and about Umar Bin Hassan, whose spoken word poetry is infused into a couple songs on the new album. We talked about when Drew met and jammed with John Paul Jones, the bassist and organ player for Led Zeppelin, and about how people sometimes get a little stir crazy on the long bus rides between gigs and have to literally run up and down the length of the bus to burn off a little of the insanity. Then we parted ways. An hour or so later, I watched the Toubab Krewe put there theories into practice, rocking the B.Side Lounge late into the night.

To read my review of the show, click here.