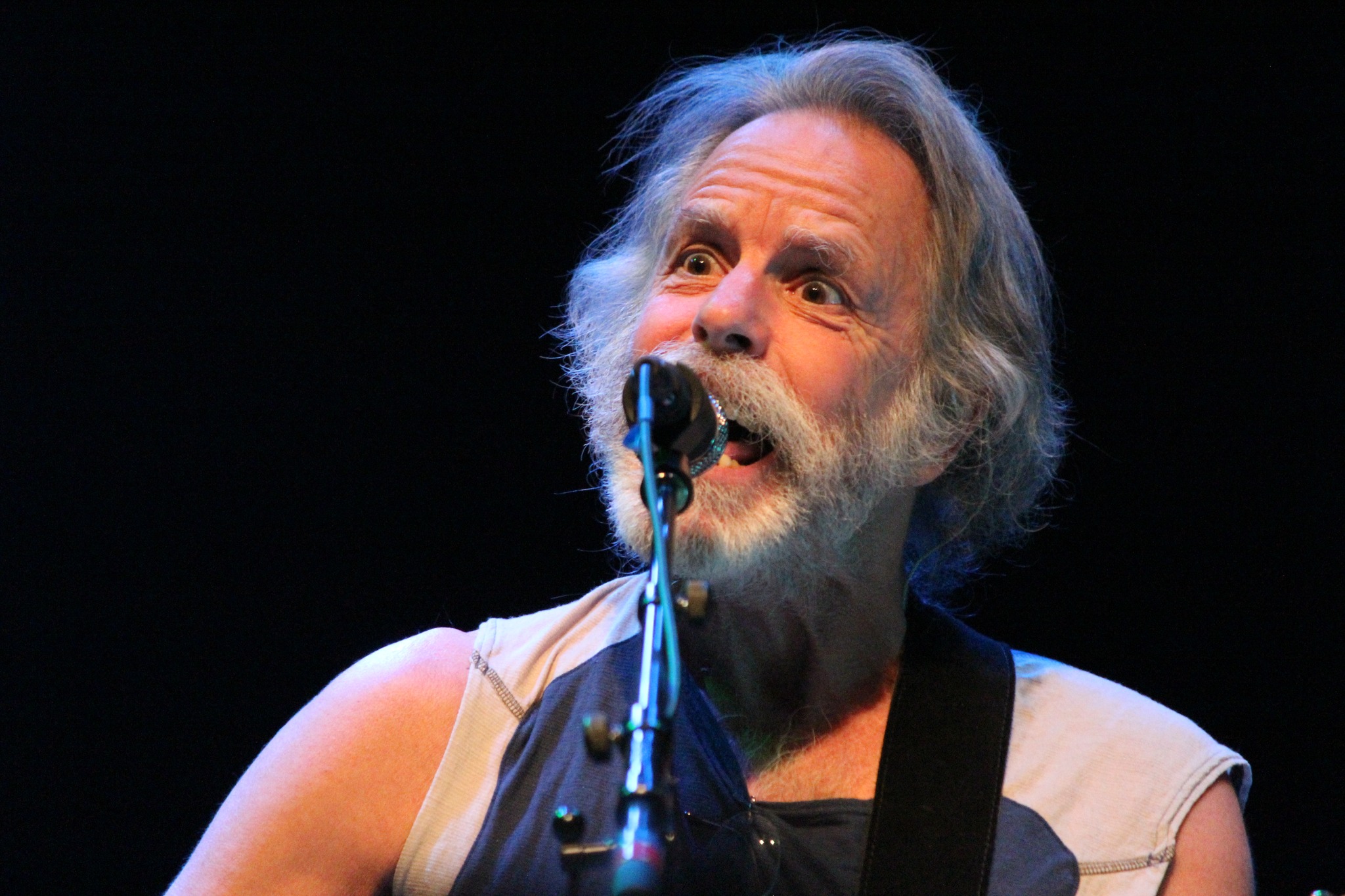

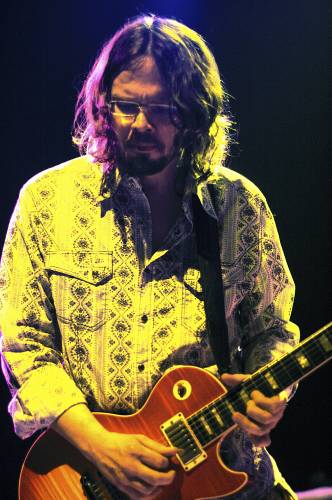

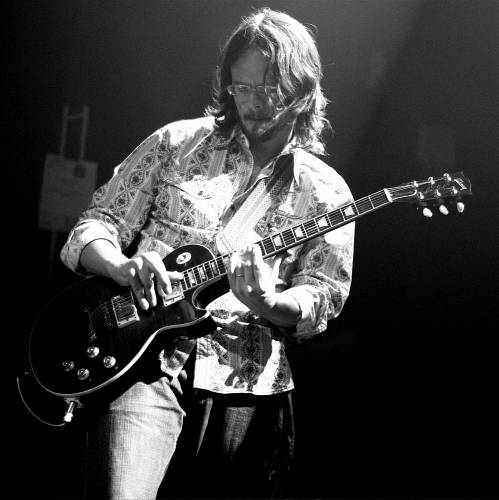

In the beginning, a father passed away and a child was born. Luther and Cody Dickinson lost their father, Memphis music legend Jim Dickinson, only months before Luther became one. Jim had always told them, “You need to be playing music together. You are better together than you will ever be apart.” Coincidentally, the Dickinson brothers were not together when Jim passed. At that moment, they were both off on their own, Luther with The Black Crowes and Cody with the Hill Country Revue. So in the spring of 2010, the North Mississippi Allstars reformed and went into the Zebra Ranch, the family’s recording studio where they had spent countless hours together with their dad, to create a record that could help them cope with the loss, and, at the same time, rejoice in his honor. The first line of Jim’s self-written eulogy was, “I refuse to celebrate death.” Luther, Cody and Chris Chew took heed and aimed to celebrate life instead; and the songs for the new record, Keys to the Kingdom (Songs of the South), came pouring out of their souls.

“As is our family's tradition, we gathered in our homemade studio and recorded,” Luther says. “We carried on as we've been taught and dealt the only way we know, by making music. Our dad used to say that production-in-absentia is the highest form of production. The credits read: ‘Produced for Jim Dickinson.’ Keys to the Kingdom is definitely our finest collaboration.”

“As is our family's tradition, we gathered in our homemade studio and recorded,” Luther says. “We carried on as we've been taught and dealt the only way we know, by making music. Our dad used to say that production-in-absentia is the highest form of production. The credits read: ‘Produced for Jim Dickinson.’ Keys to the Kingdom is definitely our finest collaboration.”

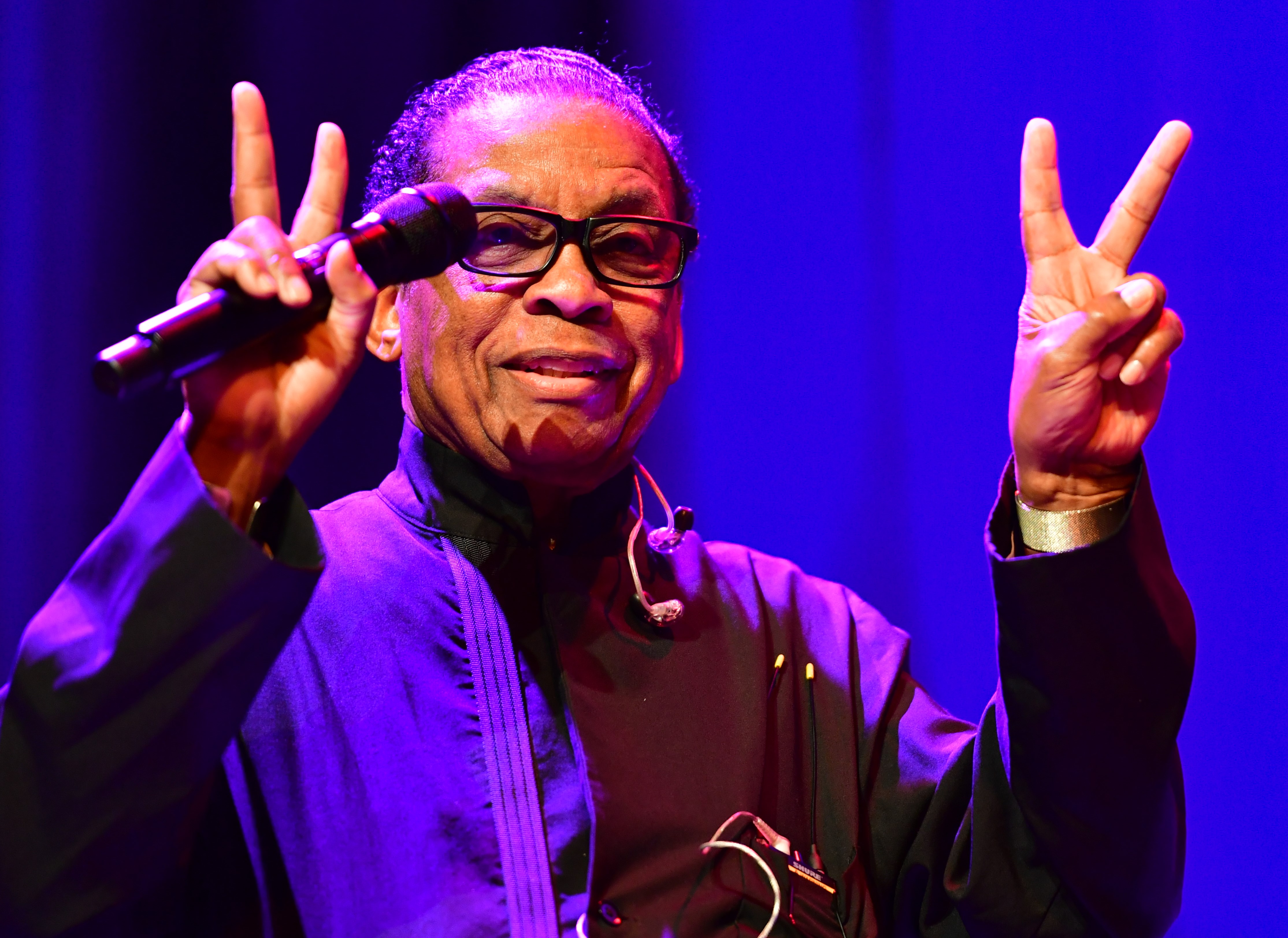

Very close friends of the family joined the band in fellowship to see NMA through this deepest of moments, among them Mavis Staples, Ry Cooder, Spooner Oldham, Alvin Youngblood Hart, Gordie Johnson and Jack Ashford (Motown Funk Brother tambourine player). All had collaborated with Jim and the boys over the years at one point or another and feel a deep kinship with the Dickinson family to this day.

Keys to the Kingdom is a song cycle, a celebratory declaration of life in the face of death as well as a musical interpretation of the Dickinson family's recent experience with the cycle of life, written and recorded honestly, fast and raw. There are moments of rock 'n roll rebellion and sexified blues, but the heart of the record reflects the journey that traverses through the mirrored gates of life and death.

“It’s said that anger is the first stage of grief and that’s how the album begins – angry,” says Luther. As such, the first song, “This A'Way,” kicks in with a boogied-up guitar line and quickly introduces the rallying cry of “I hate to be treated this a’way,” soon to be followed by the clattering country punk of “Jumpercable Blues,” with the screams of “Hey, hey, well, well, well, all y’all can go straight to hell!” It’s them against the world, gathering their gumption and keeping one another strong. The family will stay together and it will grow and carry on with its traditions in tact. This is the battle.

From there, the boys explore varying meditations on mortality, often from the perspective of their father as he is preparing to die. The songs grasp the subject matter with fierce honesty yet never become maudlin. From the Mavis Staples ghost-dance gospel soul of “The Meeting,” in which one struts and swaggers confidently through the pearly gates with head held high, to the Replacements meets Big Star-inspired rock of “How I Wish My Train Would Come,” which speaks of actually desiring to move beyond life’s struggles, to “Hear the Hills,” which depicts the acceptance and letting go experience of the final moments of a life well lived and loved, we find the boys looking for meaning and answers as they work through their pain. Spooner Oldham, Jim’s favorite piano player, lends a hand on these last two songs. Luther chose Oldham to play the “piano from heaven,” and blends it beautifully with a recording of Mississippi bugs conversing on a desolate hot summer night. As the song fades, it sounds like a distant country church house somewhere off in the woods.

From there, the boys explore varying meditations on mortality, often from the perspective of their father as he is preparing to die. The songs grasp the subject matter with fierce honesty yet never become maudlin. From the Mavis Staples ghost-dance gospel soul of “The Meeting,” in which one struts and swaggers confidently through the pearly gates with head held high, to the Replacements meets Big Star-inspired rock of “How I Wish My Train Would Come,” which speaks of actually desiring to move beyond life’s struggles, to “Hear the Hills,” which depicts the acceptance and letting go experience of the final moments of a life well lived and loved, we find the boys looking for meaning and answers as they work through their pain. Spooner Oldham, Jim’s favorite piano player, lends a hand on these last two songs. Luther chose Oldham to play the “piano from heaven,” and blends it beautifully with a recording of Mississippi bugs conversing on a desolate hot summer night. As the song fades, it sounds like a distant country church house somewhere off in the woods.

Luther explains the inspiration: “When we were little children, we lived in a house on a dirt road in between a juke joint and a lake where local churches held baptismal services. I remember hearing the music come through the woods at night and on Sunday mornings.”

The one cover on the record is Bob Dylan’s “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again.”

“One night, while in the hospital, dad had the great idea that ‘Stuck Inside’ could be done as a one-chord hill country blues song,” Luther shares. “He couldn’t talk so he wrote it down on a piece of paper and handed the idea to me. I promised him then that we would do it.”

“’Let It Roll,’ ‘Ol’ Cannonball’ and ‘Ain’t None O’ Mine’ are some of the most hardcore traditional blues originals NMA have ever laid down on tape,” says Luther. The former is a new take on a song he wrote and recorded three days after Jim passed away and originally released on a record called Luther Dickinson & The Sons of Mudboy. “Ol’ Cannonball is played in the acoustic string band tradition with Alvin Youngblood Hart on vocals and harmonica. “Ain’t None O’ Mine,” drunk on juke-joint, Peavey-amp distortion and reverb, is inspired by Otha Turner’s lusty tales of old-time, late-night country courtship and provides a necessary aspect of the cycle of life – sex.

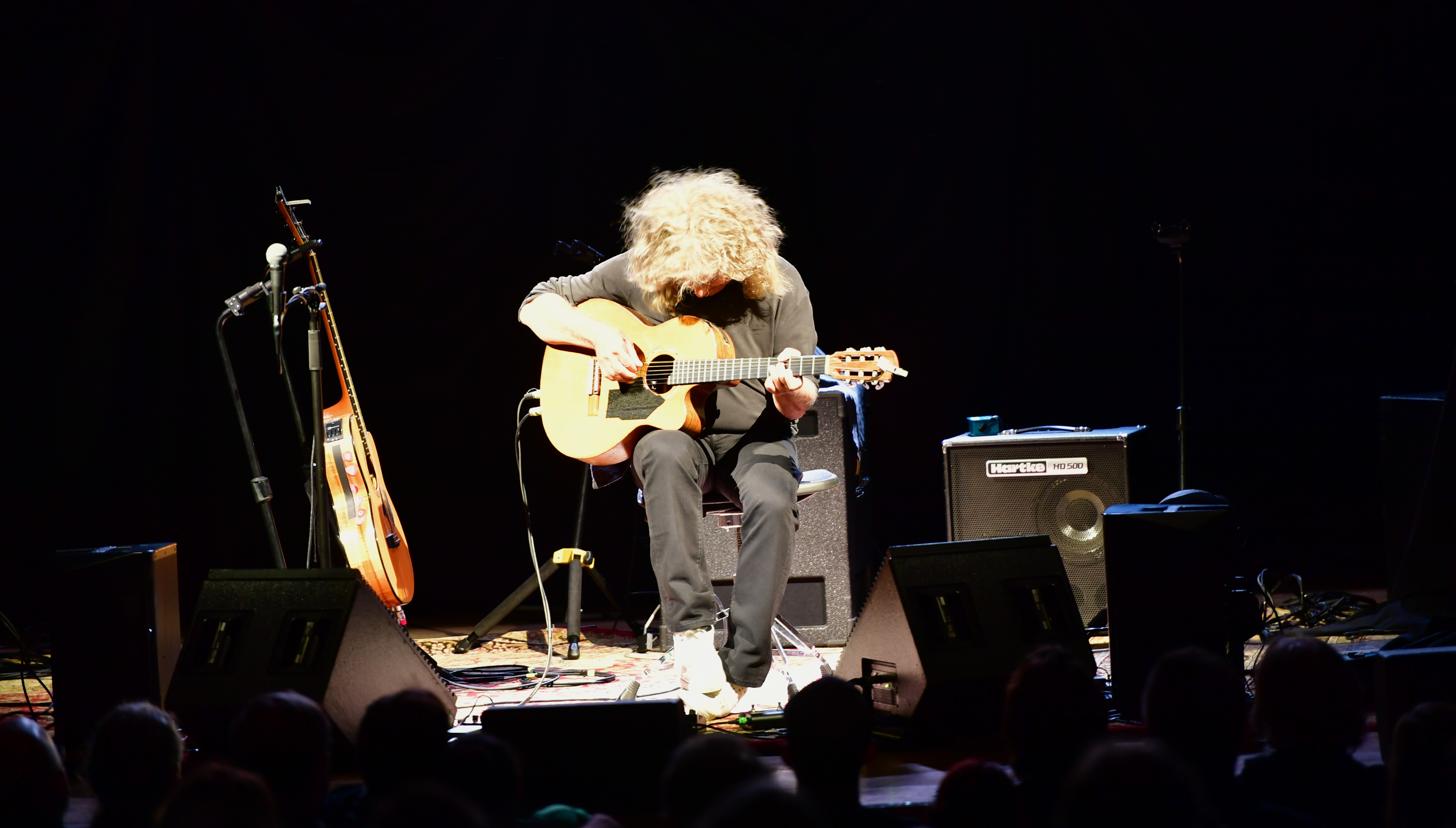

In between these three songs, sits the emotional centerpiece of the record, the ultimate love letter from a son to his lost father, “Ain’t No Grave.” The song features Jim’s old partner in crime Ry Cooder on guitar and is simultaneously heartbreaking and uplifting, gut wrenching and empowering.

In between these three songs, sits the emotional centerpiece of the record, the ultimate love letter from a son to his lost father, “Ain’t No Grave.” The song features Jim’s old partner in crime Ry Cooder on guitar and is simultaneously heartbreaking and uplifting, gut wrenching and empowering.

Says Luther, “I woke up one morning on NMA’s bus, and the lyrics to ‘Ain’t No Grave’ came to me as fast I could write them. That night, after the show, I picked up a guitar, opened my lyric book and the melody came to me just as easily. The song is brutally honest and heartfelt.”

NMA ends the cycle with two somewhat lighter takes on death. “New Orleans Walkin’ Dead” is a humorous zombie-rock take on the notion of resurrection, while “Jellyrollin’ All Over Heaven” is in the spirit of a New Orleans funeral procession during which the marching band plays uplifting and joyful music on the return parade from the burying ground. Once again, Oldham plays his angelic piano, and the bugs carry the spirit of the Mississippi night as they have for thousands of years and the record fades to black.

Jim always advised in a very no-nonsense way, “Play every note as if it's your last because one of them will be,” and that’s just what NMA set out to do on Keys to the Kingdom. The results are powerfully played and deeply visceral as the best blues music is - spiritual without being god fearing, heavy without being depressing.

Jim always advised in a very no-nonsense way, “Play every note as if it's your last because one of them will be,” and that’s just what NMA set out to do on Keys to the Kingdom. The results are powerfully played and deeply visceral as the best blues music is - spiritual without being god fearing, heavy without being depressing.

“In the end,” Luther says, “We recorded our best country blues and Mississippi rock ‘n roll record yet -- as if our lives depended on it.” Ten years after the release of their debut album, Shake Hands with Shorty, Chew sums it up: “This is grown folks music.”

On Keys to the Kingdom, some children are born and others become adults; naïve idealism gets squashed by stark realism, yet there is no choice but to move on, and so they do -- the quest for joy, celebration and truth palpable in every note of the mighty NMA sound.

It’s not a question of whether or not.

It’s a question of when.

-Luther Dickinson from “The Meeting”

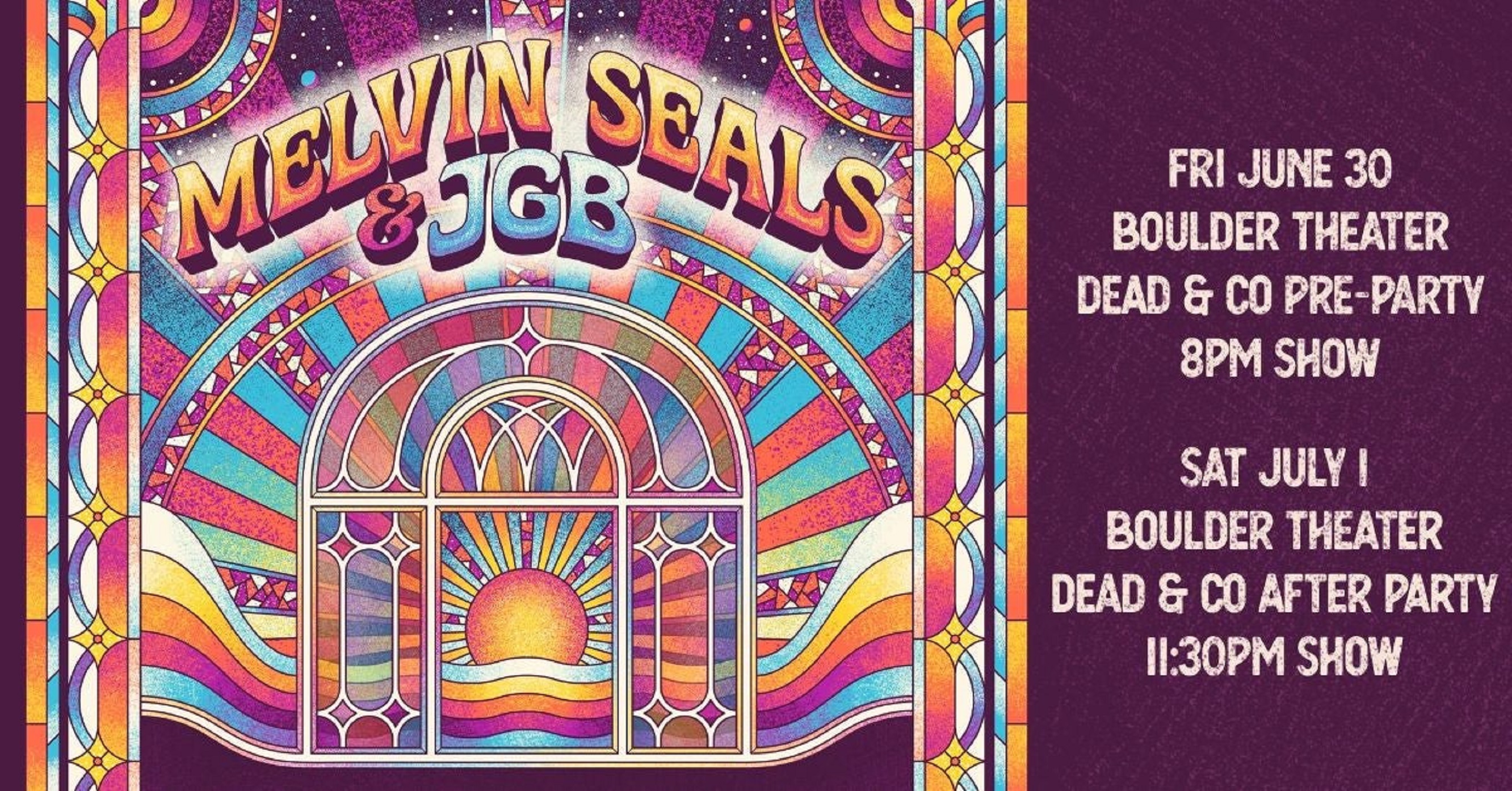

Tickets are on sale at Boulder Theater Box Office. Call (303) 786-7030 for tickets by phone.

Tickets are also available through our website @ www.bouldertheater.com.