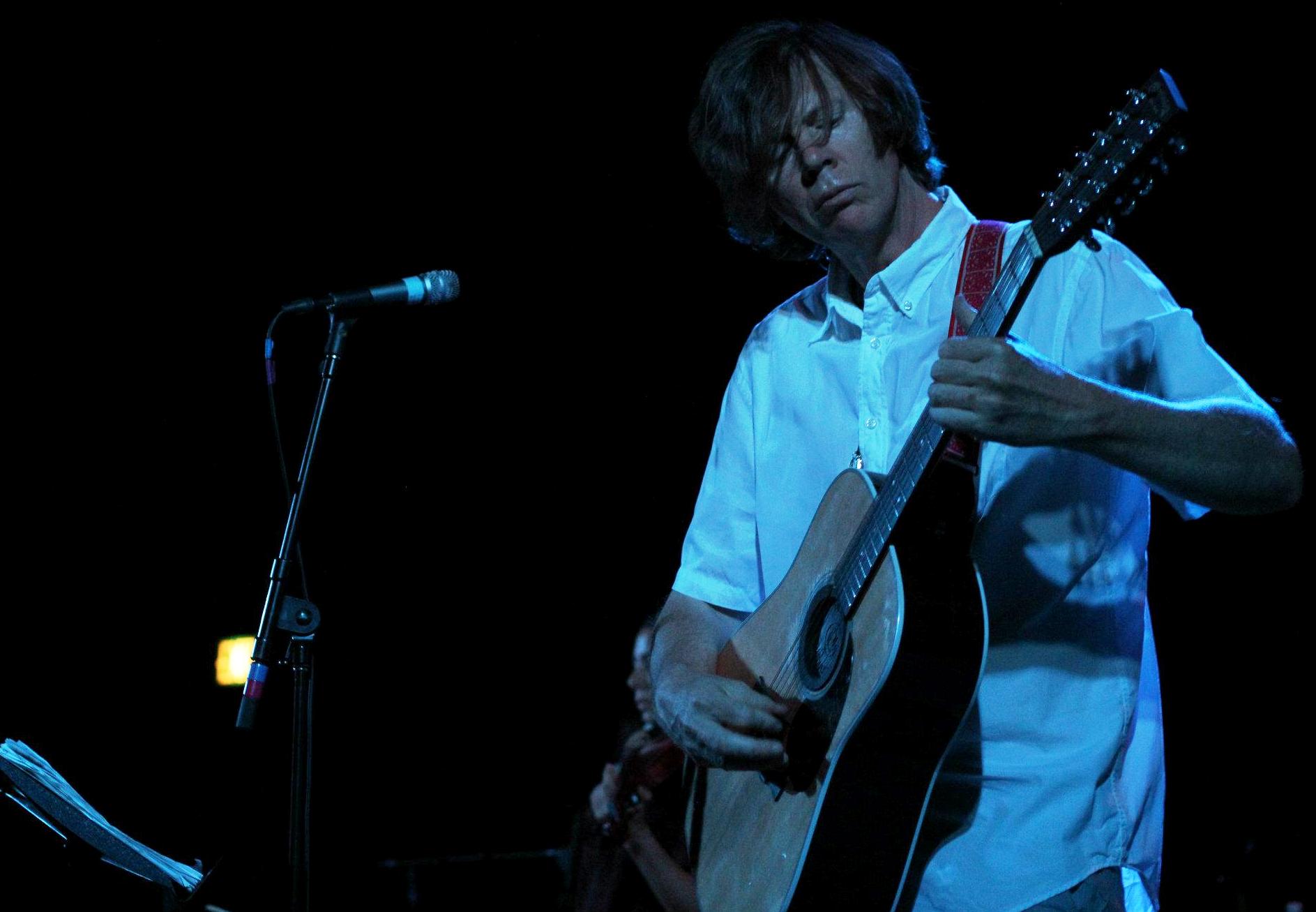

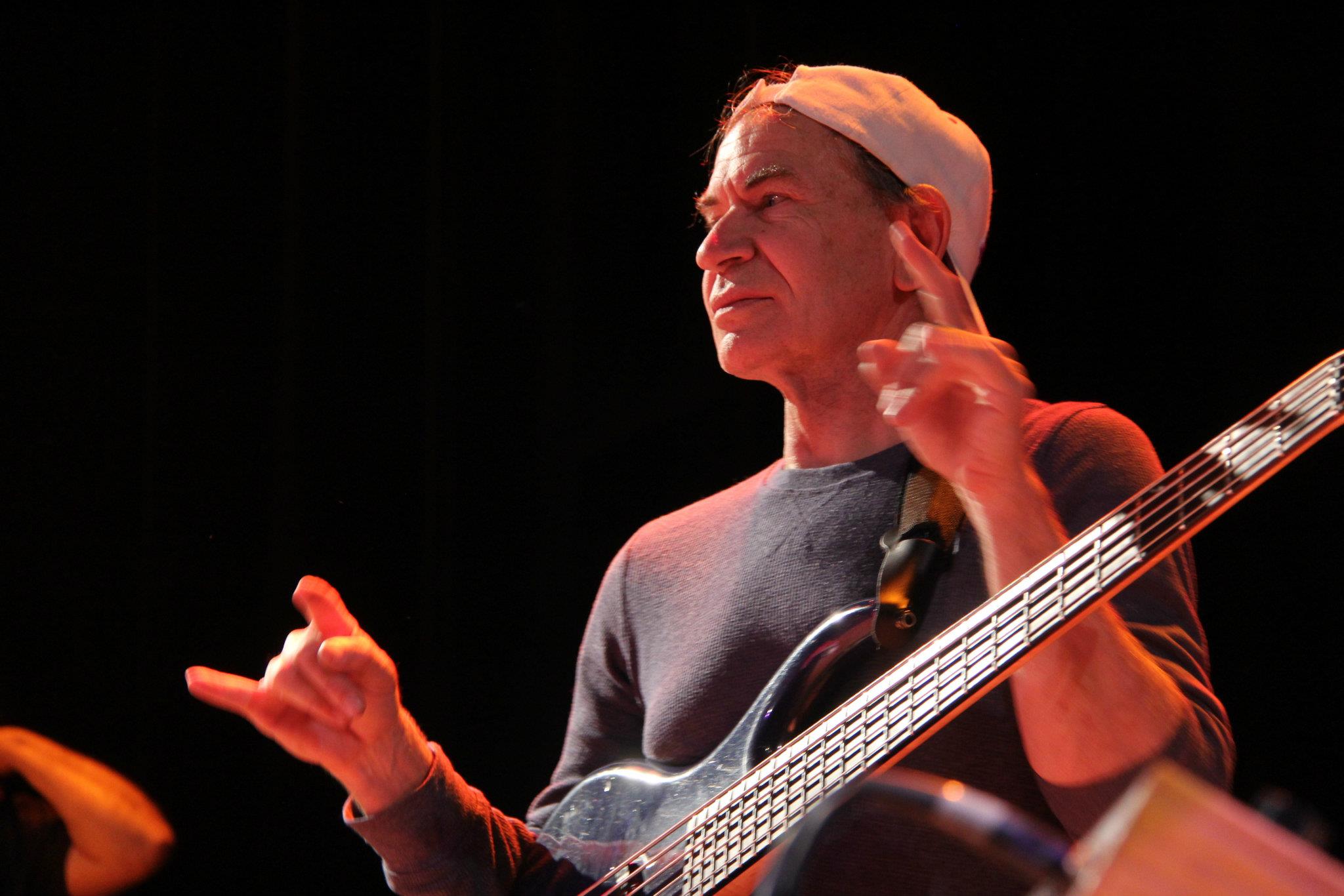

It was sometime in the early 90s when I first heard Hot Tuna. One of the older hippie kids in my neighborhood who used to flow me Dead tapes (and weed) said "hey man, you dig Hot Tuna?" I was the furthest thing from hip to what he was saying, and probably replied with something along the lines of "I don't know them." He said something like "shit, you don't know Tuna. You gotta get up and go to school, son." A cassette tape (and probably some weed) passed hands, and shortly thereafter I was sitting in my room, likely stoned, as the acoustic sounds of Jorma and Jack, formerly of Jefferson Airplane, currently (then, and now) the guts of Hot Tuna, blared through my sound system. "Nickel is a nickel, dime is a dime, need a new girl, she won't mind, tell me how long, do I have to wait? Can I get you now, or lord, must I hesitate," Hesitation Blues came through so loud and clear. Jack rolled the groove like it was all he knew and Jorma, damn, he played that acoustic guitar like it was nobody's business...

From his time with Jefferson Airplane to his ongoing legacy with Hot Tuna, Jorma Kaukonen may never stop. His current endeavor, Fur Peace Ranch, is physical proof of the music that flows through this man’s veins. Jorma took time to speak with the Grateful Web about his beginnings, his passion for teaching and his relationship with Jack Casady—a brotherhood that has truly stood the test of time. Kaukonen is an icon, but at the heart of the matter, he’s really just a super-cool, regular guy with a penchant for playing the living hell out of his guitar.

GW: For the past fifteen years you and you wife Vanessa have owned and operated the Fur Peace Ranch, a 119-acre music and guitar camp in southeast Ohio. It looks like a paradise. You’ve got private cabins, workshop space, a 32-track recording studio. Could you give us the run-through on how it got started and what goes on there?

JK: You covered all of the high points that look good in print. First of all, it’s a beautiful part of the country; it’s a landlocked farm, as you mentioned, 119 acres. We have great facilities. We started out—I’ve been teaching on and off for years and I got back into it when I started doing some videos for Happy Traum in the late 80s, and the ranch was an outgrowth of us getting this beautiful piece of property. We just finished a camp over the weekend, and one of the things that happens that is difficult to really put into print or to talk about without sounding sappy, is the kind of musical community and fellowship that happens every weekend that we are open. Now we know that all of us—you and me and our buddies—that the music that we love—that there’s sort of a built in fellowship to that, but it’s just a microcosm when you get like 25 people for a four-day weekend and all that they have to do is to share their love of music.

GW: You get a lot of folks that come to the ranch once, and then come back?

JK: We do. We call them “return offenders.” Luckily we have a really high return rate; 80% returns.

GW: And you cater to people of all skill levels?

JK: Absolutely. If somebody is going to come to the camp, they’d want to look at the website or talk to Vanessa or Brett and make sure that they’re in a class that’s not going to be over their head, because that’s not really fun; but we have something for everybody and it’s all fun.

GW: When did you first get interested in teaching?

JK: Well, it’s funny that you should mention that, as we are speaking in a “Grateful World.” When I moved to California in 1962, the first weekend that I was there I went to a hootenanny--some of us are old enough to remember what hootenannies are—and at this hootenanny was none other than Janis Joplin and Jerry Garcia and some of his pals. So I met them and Paul Kantner and a bunch of people that have sort of become luminaries over the years, and Paul was teaching at a place called Better Music Company. I was in school, I had no money, I was playing out, but I wasn’t making any money playing out, and he said “listen, people will pay you to teach them how to do this,” and I went “you’re kidding me,” and he said “no, they really will.” So I went to the music store and basically they rented us a studio. It was a tiny basement; you had to climb down a ladder to get to it. My lessons went for three dollars a half hour, and at one point I had over a hundred students a week. For the first year that Jefferson Airplane was together, I still made more money teaching.

GW: Do you find that by doing the teaching thing that you learn a lot from your students as well?

JK: There’s no question about it. This last class I had was a Level three, and some of the players were very advanced, but you know something, players don’t have to be advanced for you to learn from them. There’s always something to be learned. The beautiful thing for me about playing the guitar in particular or music in general, is that you’re never done.

GW: You host concerts at the ranch as well?

JK: We do.

GW: And you broadcast those on local radio stations?

JK: We do. We have a local NPR affiliate, which is WOUB out of Ohio University in Athens. If you go to WOUB.org you can listen to a lot of our archived shows. We have a weekly show there—it’s an NPR station—and we’ve recently been picked up by a number of stations around the country. It’s very cool.

GW: You mentioned on your website that you have some future plans for the ranch. Can we get a little sneak preview on things to come over there?

JK: Here’s the deal—the ranch certainly has my name on it, but the truth of the matter is that it’s really my wife’s business, and she is always thinking about stuff. She’s just started a non-profit thing, which is going to be The Fur Peace Ranch Arts and Cultural Center, and we’re going to be doing some more stuff. I’ve been sworn to secrecy; I can’t really divulge too much, but I can say that we are going to have a full-time arts and cultural thing that focuses on my era, in general. But also, we are not going to get lost in the past and we’ll do a lot of modern stuff too.

GW: So, Jorma, last year in April, Hot Tuna released Steady As She Goes, the first Hot Tuna studio album in 20 years. It was recorded at Levon Helm’s studio in upstate New York with mandolin player Barry Mitterhoff and drummer Skoota Warner. In the 20 years since the last studio record, had you been amassing ideas for songs that you held out on putting out on your solo records and were saving for Hot Tuna?

JK: Every time I have a project come up, I pretty much use up all of my songs. But Jack and I talked about this a lot. As you know, Jack and I have never quit playing, but we just didn’t have it together—either from our point of view or from the record company’s point of view, to make another project. But everything came together for us—with Larry Campbell and the studios, and I wound up co-writing a bunch of stuff with Jack and Larry and we wound up having so much fun. It’s one of these things that is like a perfect storm of creativity and all I can say…people say “why did it take so long”… and all I can say it that the time was just right. Stick with me here just for a second.

[to son: Zack, do me a favor and take the GPS out of the car, will you? And I’m going to stand up and finish talking, okay?]

Thanks, man. I’m getting my wife’s car serviced, that’s why I’m up in Columbus today. They lent me a car and my son and I went over to the Lamborghini dealer and looked at some things that we’ll never be able to afford.

GW: Did you take any test-drives?

JK: No. I told my wife that they didn’t even come out to see if we were serious about buying. But we took a lot of pictures.

GW: Nice.

JK: But anyway, to get back to what we were saying…Hot Tuna…a perfect storm of creativity…and one of the things Jack and I sort of chuckled about—at this point in our lives we’ve grown up enough that we don’t hassle in the studio. We did the whole project in about ten days, we had a great time, nobody got heartburn and we still love each other.

GW: Beautiful! You said that on the new record, you took an approach to the songwriting that was similar to the way you recorded back in the day with the (Jefferson) Airplane. Would you tell us about that?

JK: Yeah, sure. I’ve done a lot of recording over the years and when I do my own projects I always try to get other people to play with me, but sometimes you overdub yourself, and I’m not fond of doing that because it sort of takes the excitement out of it, and in this project, because Larry is such a great guitar player, and Barry is such a great mandolin player, when I got them to lay down tracks for me, or we worked together, the time came for doing overdubs—for example, on that tune “A Little Faster,” it was like overdubbing an Airplane song, in the sense that I couldn’t second guess every move that I made because I had other people that I was working with.

GW: In a couple of weeks you’re heading to the Wanee Festival, and it looks like you have a pretty busy summer of solo shows, and then electric and acoustic Tuna shows. I’m out in Colorado and I’m looking forward to seeing you in Denver. Who are the personnel for the road? Will Barry and Skoota be with you?

JK: When we’re down at Wanee, it will be the personnel of the album. It will be me, Skoota, Jack, of course and Barry. The only people missing from this one will be Larry and Theresa. But he’s a busy guy and he’s got to keep Levon going up there. To be honest with you, I’m not looking at my website right now and I can’t remember whether our shows in Colorado are going to be acoustic or electric. If they’re acoustic, the only difference will be that Skoota won’t be with us.

GW: I think they are electric, if I recall correctly.

JK: Well, then it will be the quartet.

GW: I wanted to ask you about your taping policy at shows. About five or six years ago you guys decided to no longer permit taping of Hot Tuna live performances. What sparked that change?

JK: Well, you know, there are a lot of things, and the whole taping thing is a two-edged sword, and I’m completely aware of that. One of the things that we realized is that we can tape some stuff ourselves and offer them for sale, which we do. One of the other things is, and I know I’m going to catch a lot of flack for this, but I’m going to throw it out there anyway—I have a lot of friends that are tapers, you know? But when you get into the taping thing, you get—a lot of the time—and I’m not castigating tapers as a genre, but you get a lot of people that are self-entitled, arrogant, in-your-face, difficult-to-deal-with people, and I’ve just really had enough of that. I know that a lot of bands do things differently, and I look at it this way: whatever works for you is fine. Because I mentioned it is a two-edged sword, I will mention this also: we don’t allow video taping or any of that stuff, because if it’s going to happen, we would like to do it ourselves, but…but, the reality of the fact is that there is always somebody out there doing something like that, and you know he’s going to jail for it…and I’ll tell you—every now and then, something happens that somebody else has taped and recorded that’s so cool that I’m glad they did it. Officially, we do not sanction this, but every now and then, I’m glad it happens anyway.

GW: You still record for your own personal archive.

JK: Absolutely, absolutely.

GW: So, they (recordings) do exist, and very well may surface in the future?

JK: They pop up on iTunes, we have a site on iTunes.

GW: Another thing I’ve read is that you discourage cellphone usage for photos and videos at shows and I completely agree with that. In this day and age, it seems to take away from the intimacy of the performance—

JK: It really does—

GW: You’re trying to watch a performer on the stage and you see, like, four phones in your face—

JK: Listen, it’s the way it is, it’s intrusive. I go to shows and if someone’s doing it next to me, it’s aggravating. When I go to a show, I’m there to embrace that moment, and anything that takes away from it is a drag.

GW: It’s a shame. People, instead of looking at the performer and enjoying that moment, are looking at it through a phone like they’re watching television, and it kind of defeats the purpose of going to see a live performance.

JK: If you think about it, that’s really a sad commentary on today’s society.

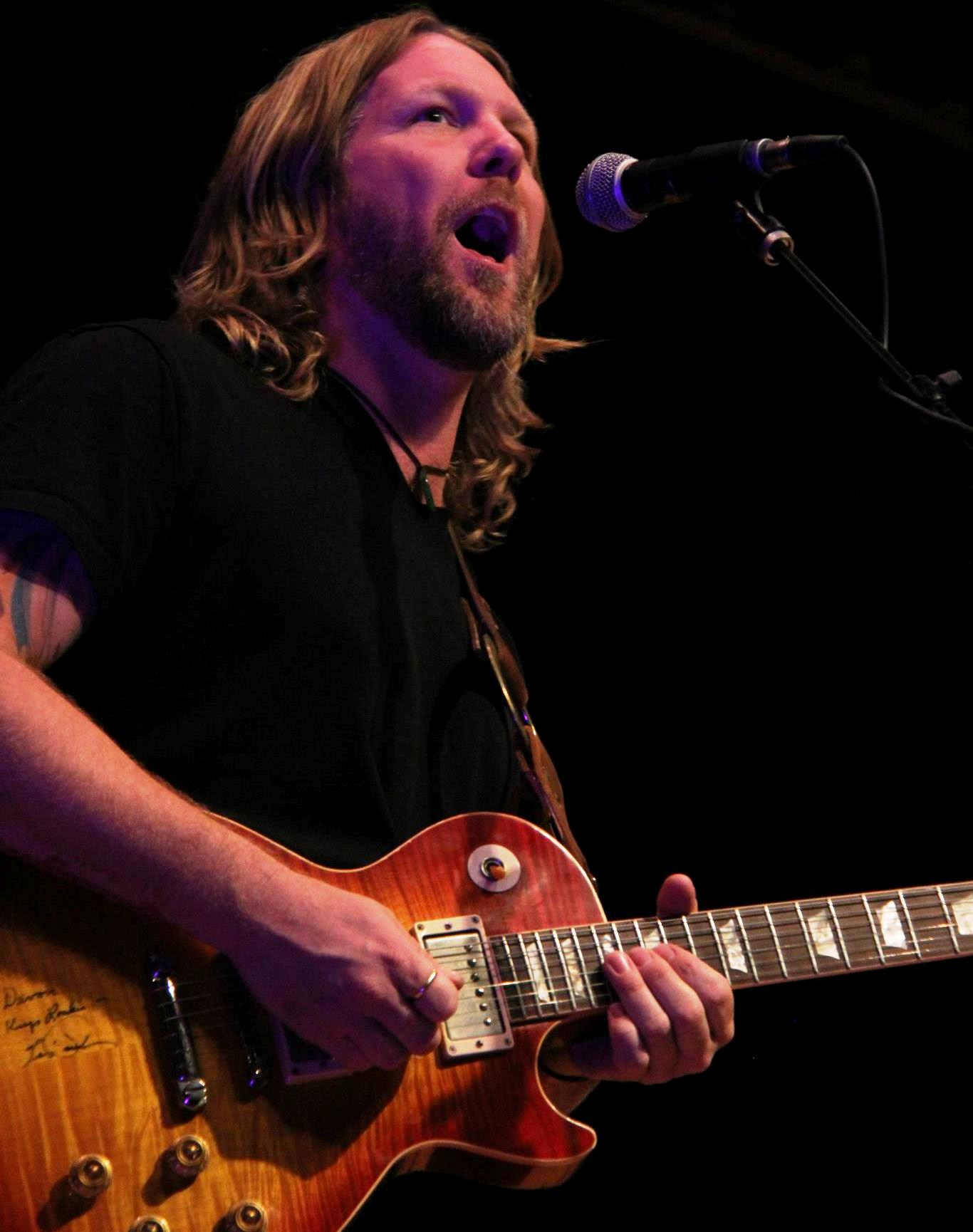

GW: Down at Wanee, you are doing some Fur Peace workshops, with your partner in crime, Jack Casady and also Warren Haynes and Mickey Hart.

JK: Yeah, Mickey’s there, Oteil Burbridge is going to be there. The Wanee folks came to Vanessa and asked if we could take some aspect of our workshop on the road. Jack and I are doing an actual workshop with some guitar and bass players that is going to be limited to like eight or ten people, and then we’re going to have a bunch of Q and A. We’ve never done this before, so this is going to be an experiment for us. I think everybody is going to have a good time, and I guess I won’t really be able to comment on how it worked out until we see how it works out. But we’ve played Wanee a lot; I really love the vibe down there, and I think it’s going to be a lot of fun.

GW: It sounds great! So this is the first time that you’re taking the show (Fur Peace) on the road?

JK: We’ve taken the show on the road, in terms of doing full workshops…we’ve done upstate New York at the Full Moon Resort, and we’ve been to Hawaii, but this is the first time we’ve done something in a festival setting. When you have four days to do a workshop, you get a chance—and you’re having two or three workshops a day—you can get into things on a level that you obviously can’t do at a festival, but, what we hope is, that—I mean, I know we’re going to be able to communicate something, and maybe it will get some people excited, but you either come to our workshop or somebody else’s or just expand the whole musical community.

GW: Do folks need to sign up for these workshops in advance of the festival? Or is it kind of a first-come, first-served on site?

JK: That’s a good question, and to be honest with you, this is something that I should know, but I don’t know. Check with the festival site, and see what they say about that. Honestly, I just don’t know. If they go to the site and can’t find out, they can certainly email info@furpeaceranch, and we’ll take care of them from Ohio.

GW: So, Jorma, it’s seems like you’ve kind of done it all so far in your lifetime. From all of your musical accomplishments to the creation of Fur Peace, your website is incredible, you’ve got Breakdown Way, which is online music lessons, and I really, personally, love your blog, I’ve been reading your blog—

JK: Thank you very much—

GW: One thing, in the most recent entry, you said “my rewards don’t come from me anymore,” referring to teaching your daughter how to ride her bike. While the parenthood thing is such a beautiful, selfless part of life, are there any selfish, musical Jorma endeavors on the horizon. What’s next for the guy who has seemingly done it all?

JK: Well, I’m just the luckiest guy in the world because I’ve been able to support myself and my family doing what I love to do all of my life. I guess I’m just looking for more of the same. I’m fortunate that I get to keep learning all of the time, that’s exciting, and I guess that’s selfish on some level, but on another it’s not because I get to pass it on, too, so…life is good!

GW: Well, Jorma, I’m going to let you go, but thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us. It was truly an honor.

JK: Well, thanks, man. Thanks for being interested…and, you’re out in Colorado, huh?

GW: Yes sir.

JK: Well, listen, why don’t you come by and see our show, and lets talk to each other face to face.

GW: Sounds great! I totally look forward to it.

JK: Cool, man. Thank you so much.

GW: Alright. Take care, Jorma.

JK: Alright, brother. Bye-bye.