As an ancient and integral part of the culture of Appalachia, I have a feeling songs perpetually echo across the mountains of West Virginia; but from August 2-6 a symphony rang through them from Camp George Washington Carver where over 3,500 voices and thousands more strings lilted over Clifftop during the 17th annual Appalachian String Festival. There West Virginia masters, along with traditional and non-traditional musicians and dancers of all levels from around the world competed with, learned from and entertained one another.

It was as though everyone had gathered to celebrate life as a song and a dance. Even butterflies, bluebirds and canaries joined in, fluttering everywhere. During the event, some of the nation's finest string band musicians and old-time dancers won prizes in four old-time "traditional" contests; fiddle, banjo, string band and flat-foot dance; plus one "non-traditional" string band contest. This category is growing. This year, for the first time, ribbons for best original song and best original tune were awarded and next year it will be re-vamped with a new name, "Neo-Traditional".

"We think this name more accurately reflects the reason the contest was invented in the first place – that is, to celebrate the relevance of old-time music traditions and their connections with new musical voices and styles.", the official site of the Festival states. Welcome to the new Folk Revival.

The food was fabulous, and music and miscellany vendors displayed diverse, unique and eye catching wares. Activities for children and adults alike were abundant, from basket weaving to tie-dye making, yoga and dancing. Somehow, the atmosphere and accommodations were truly, seamlessly maintained and organized in such a way that everyone from infants to the elderly, families to college students had an equal place and was equally comfortable, physically and viably.

I couldn't get to the Festival until Friday. This meant, I was certain, no parking, no camping without quite a long haul up the road to the stage, the 'normal' (i.e. not port-a-potties, too much of a city girl to get but so into that) bathrooms, the food, above all the coffee (it takes about a pot to wake me up) – all that roots of jazz. Alas for poor me! I thought.

I couldn't get to the Festival until Friday. This meant, I was certain, no parking, no camping without quite a long haul up the road to the stage, the 'normal' (i.e. not port-a-potties, too much of a city girl to get but so into that) bathrooms, the food, above all the coffee (it takes about a pot to wake me up) – all that roots of jazz. Alas for poor me! I thought.

Unbeknownst to me, (and a good thing, or I would have been really crying, "Alas and alack!" , this is exactly what I've been working on with my own music), old-time fiddler, songwriter and tunesmith Mark Simos hosted "New Tunes and Songs in the Old-Time Tradition" that afternoon in the Main Lodge from 11am-12:30 pm. It wasn't a workshop, wasn't a contest, but uniquely an open sign-up to share original compositions based on old-time tunes with the Clifftop Community.

Now, I didn't know I'd missed that yet so I was at least not utterly distraught. Still, there wasn't a campsite to be found, near or far as I could see. I noted there was a bus that went regularly up and down the mountain and that would have been fine, but I was late! I had to get photos! The Non-Traditional Music competition was in full swing! What was a wayfaring stranger to do?

I thought well, maybe I can squeeze into a space near the stage and explain to the campers that I'm moving the car soon /what I'm up to. I did that, and that worked fine for a time. I saw some of the competition, and then tore myself away with conscience nagging that someone really might need to get out for whatever reason and I should find a better place.

There was a sort of triangle by a tent where a woman was standing by her car so I again, explained myself and asked if I could park there till the competition was over. She was leaving! Instant Karma just got me – I laughingly told her and little did I know how right I was. It was then that I ran the car straight over a block of concrete that I couldn't figure out how to back it off of.

The two of us sat there trying to figure out how to get it off, finally trying to use my Yoga mat as a ramp when Keith Garvin walked by and said, "What on earth are you trying to do?" "Get my car off of this" I said "And you're trying to do that with that?" he asked, pointing to the mat. "Yes" I said. "Is that made for automobiles?" He laughingly replied.

The two of us sat there trying to figure out how to get it off, finally trying to use my Yoga mat as a ramp when Keith Garvin walked by and said, "What on earth are you trying to do?" "Get my car off of this" I said "And you're trying to do that with that?" he asked, pointing to the mat. "Yes" I said. "Is that made for automobiles?" He laughingly replied.

I had to admit that it both wasn't and that I had no other ideas, he helped me get it off, reminded me to sleep with my head up hill, (I was right on the edge of the cliff) and told me a little about himself. I discovered that he was from a town in Eastern Kentucky that I had visited frequently when I lived in Western KY, coincidence followed coincidence and I ended up spending most of the weekend as a lucky fly on the wall of the tent of the Garvins, (Keith and Michael), and Billy Wright of Kentucky Memories along with their friend Jeff Walburn.

We agreed to meet the next morning, (their tents were the ones I'd just parked my car to begin with), and I set off to watch the rest of the contest on the stage I was now within earshot and plain view of from my tent.

I went on to watch the Non-Traditional competition and was delighted by the rich diversity of the music when presented region by region. My ear and eye particularly caught by a band from North Carolina called the "Dixieland Travelers" who played Ragtime based tunes with Fox Nichols on Washtub, Chris Kefer on banjo and guitar and Seve Kruger on fiddle, Jeremiah Campbell on washboard.

I went on to watch the Non-Traditional competition and was delighted by the rich diversity of the music when presented region by region. My ear and eye particularly caught by a band from North Carolina called the "Dixieland Travelers" who played Ragtime based tunes with Fox Nichols on Washtub, Chris Kefer on banjo and guitar and Seve Kruger on fiddle, Jeremiah Campbell on washboard.

Last years winners, the Red Stick Ramblers, played that night, bringing bayou bounce and flashing fiddlesticks into the mix. Then came the finals, where the polished harmonies of Cold Cat Creek, jumped out at me from the rest, (apparently to the judges too, they won first place).

Though they placed fourth, a huge monarch butterfly picked, the Ukrainian String Band to dance to, flying around the head of the lead singer as she sang a hauntingly beautiful combination of Ukrainian and West Virginia sounds.

Afterwards, I set out to find Aaron and Josh from Special Ed and the Short Bus, who I knew were somewhere around...

A rollicking ruckus from a building to my right caught my ear. I stepped in and found myself in the middle of a square dance. People of all ages and cultures, some who were masters of the art and some, who were learning, moved in kaleidoscopic patterns as a band played and a caller taught and gave steps. Just as I was getting ready to leave, I saw Josh.

A rollicking ruckus from a building to my right caught my ear. I stepped in and found myself in the middle of a square dance. People of all ages and cultures, some who were masters of the art and some, who were learning, moved in kaleidoscopic patterns as a band played and a caller taught and gave steps. Just as I was getting ready to leave, I saw Josh.

After a dance with him, followed by a waltz with a gentleman from Lexington, VA, (I felt very Scarlet O'Hara), we set off to find Aaron and soaked in the sounds that poured from tents of musicians from Louisiana, Canada, Virginia, North Carolina – everywhere you can think of really, each with their own unique energy and voice.

"People tend to camp by region here" Aaron said. "That's funny," I replied, "My music comes more from my time in Kentucky than anywhere else and I didn't know that but just ran my car straight into Eastern Kentucky and Nashville." I turned in early as someone sang "Jack of Diamonds" nearby and from the window of my tent on the edge of one of Clifftops' steep hills I gazed at a sea of twinkling diamonds in the sky…

It seemed I woke up in a place where all time was keeping time and none was actually kept. The hours flew by like the bluebirds. Around 9 are (I think) I went to talk and play with my new found concrete helpers. I kept trying to wake up, never feeling like I completely did, though I drank coffee upon coffee upon coffee. Eventually, I asked what time it was, and was told, after some effort (hardly 100 out of those 3,500 people there had a watch), it was 3. "When did it get to be 3?" We all asked.

Time for me to go watch the Traditional Music Contest, where the Georgia Jug Huggers and other fantastic bands played, again, each reflecting unique regional differences underneath a unified theme, (kind of like America itself). That night, finalists Whoopin' Holler String Band won first place but I thought the encore performances of Downward Dogs, Nanny Goat Vibrato and Orpheus Supertones of Avondale, Pa were equally engaging.

Time for me to go watch the Traditional Music Contest, where the Georgia Jug Huggers and other fantastic bands played, again, each reflecting unique regional differences underneath a unified theme, (kind of like America itself). That night, finalists Whoopin' Holler String Band won first place but I thought the encore performances of Downward Dogs, Nanny Goat Vibrato and Orpheus Supertones of Avondale, Pa were equally engaging.

Then I went back to playing, this time listening to an incredible dulcimer player from Virginia and joining a group in a tent with Mr. Walburn and Kentucky Memories that also included everyone from yours truly to a retired Circuit Court Judge from Virginia. Again, I fell asleep looking at a window of stars and listening to those who played into the morning light.

My new friends remarked that it would be nice if life were like that all the time and I agreed. In retrospect, I think perhaps it is, we just don't always notice because we're too busy watching the time rather than keeping it.

I kept a journal while at the festival and wrote, after the 2nd day, "Here you see firsthand that life is a dance. We are a song. Within individual groups, like cultures, societies, we bear marks and draw our individuality from, our steps so to speak. Some choose to go as far as they can publicly, some privately, but within yourself, you can't help but do it. Some people stay in one place. Some people travel and take it wherever they go, sometimes adapting and immersing themselves to and in different traditions too. But wherever they go, there they are.

"It's not so different now than it was before, when the songs and traditions we now know as old-time were formed. A sense of timelessness is therefore heard in the music, traditional and non-traditional. A sense of timelessness pervaded our environment and the transitions could be seen right there, in the generations present. Music is a living, breathing thing, growing as it flies, sings, skips and echoes across the mountains."

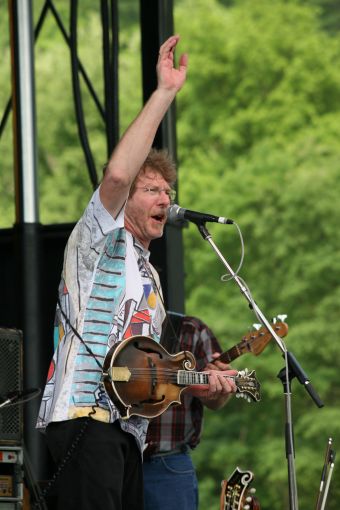

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT JEFF WALBURN

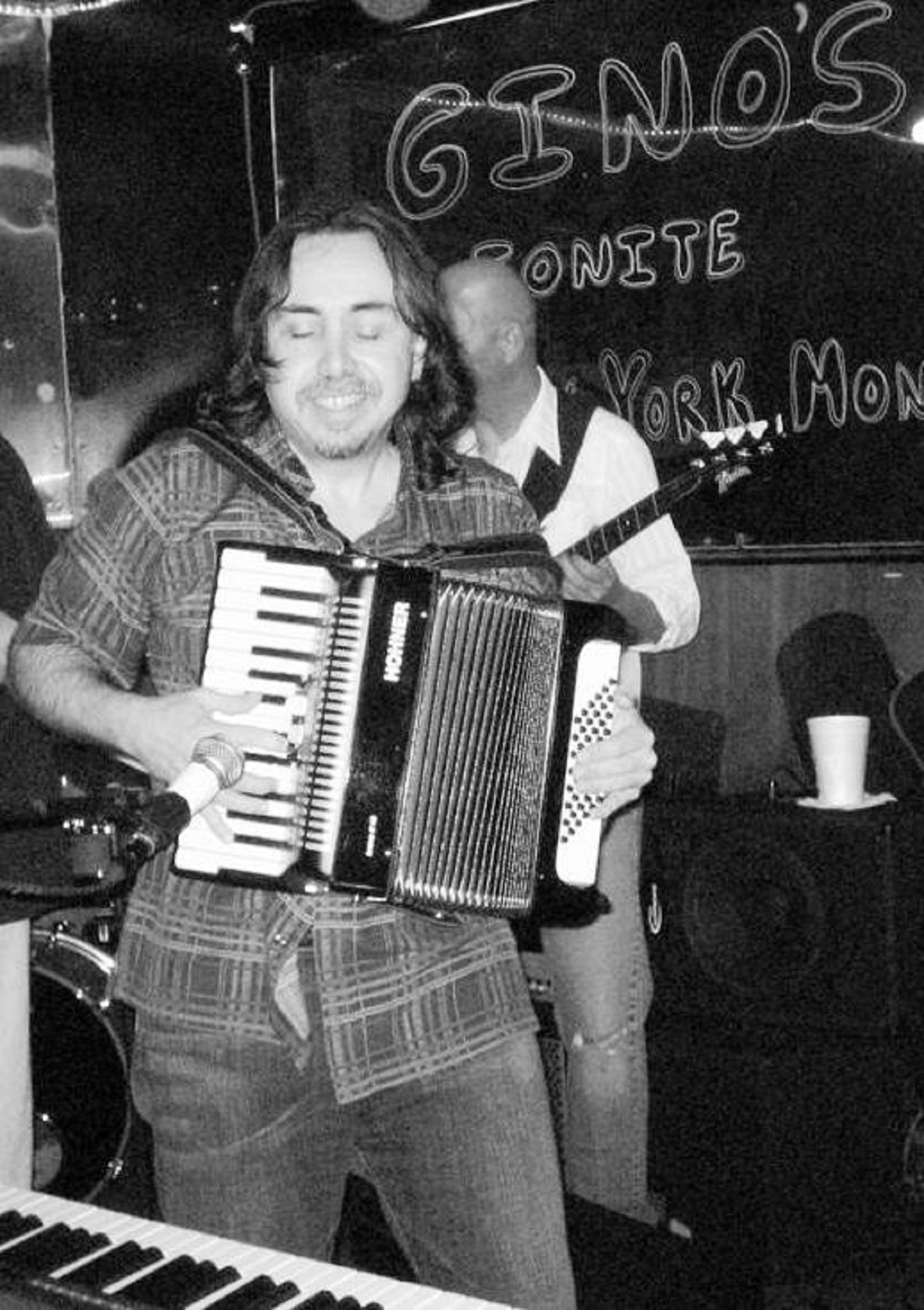

Jeff Walburn, a singer/songwriter living in Greenup, Kentucky, who records on Jeff records on Hopalong Recordings Label, BMI and Channelcat Productions. Inc. didn't win at Clifftop but has some other fish to fry. He'll be playing Sept. 20, at BB Kings' Nashville for Outlaw Americana Nite along with Michael O'Neill, Jen Cass and Douglas and Talisha Williams.

Jeff Walburn, a singer/songwriter living in Greenup, Kentucky, who records on Jeff records on Hopalong Recordings Label, BMI and Channelcat Productions. Inc. didn't win at Clifftop but has some other fish to fry. He'll be playing Sept. 20, at BB Kings' Nashville for Outlaw Americana Nite along with Michael O'Neill, Jen Cass and Douglas and Talisha Williams.

A member of the Americana Music Association, he's had songs recorded by Carla Van Hoose, Nancy Apple, (formerly ZZ`Tops' Road Manager) and Rob McNurlin. His new CD features with Grammy winning mandolin player Don Rigsby. And these are just a handful from Walburns' bucket of distinctions.

I asked him what inspired his songwriting and he said something like, "Well, I try to tell real stories; stories of relatives, murders, current events; even stories I make up are real in a way…when you write, when you use your imagination, you can be anything. You can be a sailor, a bayou hoodoo man…" And his new CD, Coast to Coaster, (named in part, he says, because of people's inclination to turn CDs' into coasters) reflects what he describes well.

Like most old-time or new old-time musicians I've met, he starts with, "It's in my blood." when asked how he started playing. His grandmother wrote songs in the early days of recording, sending them off to labels and others recorded them. "She said", Jeff told me, "and I'm inclined to believe her, that she wrote, "I Could Have Danced All Night". There's a big trunk in the family full of her records, I'd love to go through it one day."

Some of his stories come from his family background. His great-uncle was a prize-fighter who worked in the quarries. Other family members were sharecroppers. "At night", he said, "They'd go down to the locks to fish. They'd pass around water, whiskey and a guitar." A family fiddle hung on the wall of his childhood home no one was allowed to touch because it bore the muddy handprint of one of these relatives who fell as he died leaving his mark there. "I used to try to reach it", Jeff laughed.

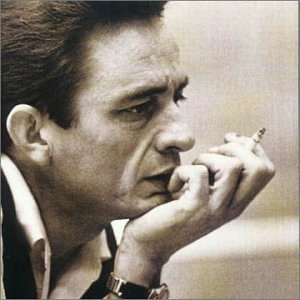

Like many teenage boys, he picked up a guitar but not only started singing and playing but writing. "While his friends played rock I played Americana. They gave me a little heat about it but I kept right on anyway." He was 'Country When Country Wasn't Cool'. Stop at the song title when thinking of Barbara Mandrell as relates to his music. Think more 1% each Dylan, Cash, Neil Young, Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger with the remaining 95% Jeff Walburn.

A remarkable lyricist, he is also a talented guitar and harmonica player. His music reflects a variety of sounds, from Cajun to the hills he lives in. In addition to musical influences like the above mentioned artists, some ragtime and jazz seems to creep in every now and then as well in his groove and chord progressions. When I asked him how that was so he said, "Well, it's a river thing. A lot comes up and down the Ohio."

Seems to me, above all, it's a Jeff Walburn thing. And that is something. Keep an eye on him, I have a feeling he's going to keep on going places and cross more than a few rivers as he goes.

ARTIST SPOTLIGHT MICHAEL GARVIN, KEITH GARVIN AND BILLY WRIGHT, KENTUCKY MEMORIES

Michael Garvin from a musical family and plays a variety of stringed instruments, (I imagine most of them, and his distinctions include placing in the National Merle Travis Thumb picking Guitar Contest in 2000, at age 17). He has chosen the fiddle as his primary imagination extension of the moment. For Michael, this means he's learned over 200 old time songs, each minutely different in style, by ear in less than 4 years.

He's just launched a group called Kentucky Memories with his father, jaw-harp and bass guitar player Keith Garvin and mandolin virtuoso Billy Wright, (who also plays a variety of string instruments). They'll be playing with Jeff Walburn at B.B. Kings' on the 20th.

He's just launched a group called Kentucky Memories with his father, jaw-harp and bass guitar player Keith Garvin and mandolin virtuoso Billy Wright, (who also plays a variety of string instruments). They'll be playing with Jeff Walburn at B.B. Kings' on the 20th.

However, the main focus of the group is Michaels' goal of accurately representing Old-Time fiddle styles from Eastern Kentucky, honoring greats like Buddy Thomas, George Hawkins, Bob Prater, Jimmy Wheeler, J.P. Fraley, Ed Haley, and Kenny Baker.

When I asked him why old-time he said, "Well, I could be playing just about anything, rock, metal, bluegrass, but it seems very important to me to keep these old songs alive. The people who kept them before my generation weren't recorded until they were so old, it was a loss. I'll be recorded from the start." And he is too. Via a 2004 grant from the Kentucky Arts Council he is apprenticed to master fiddler Roger Cooper. He is featured on Coopers' Rounder CD and the two have played at various events sponsored by the Council.

Keiths' father, Bert Garvin, met and ultimately played with Bill Monroe through his brother, who kept his hunting dogs. The two often hunted and played music together and, when he was around Michaels' age he went to Nashville, along with John and another brother, Erin and played with him there. "Monroe told Bert that if he wanted to stay, he'd be the best banjo player there", Keith said, and "That he'd see to it that he was. But He had a railroad job and a family and decided to stay in Eastern Kentucky." Bert also played with Blind Ed Haley and recorded with the Fraleys on Rounder Records "Kentucky Old-Time Banjo" a few years ago.

Keiths' father, Bert Garvin, met and ultimately played with Bill Monroe through his brother, who kept his hunting dogs. The two often hunted and played music together and, when he was around Michaels' age he went to Nashville, along with John and another brother, Erin and played with him there. "Monroe told Bert that if he wanted to stay, he'd be the best banjo player there", Keith said, and "That he'd see to it that he was. But He had a railroad job and a family and decided to stay in Eastern Kentucky." Bert also played with Blind Ed Haley and recorded with the Fraleys on Rounder Records "Kentucky Old-Time Banjo" a few years ago.

With that background, it's no surprise that Keith and Michael are the remarkable musicians you'll find them to be when you listen to Kentucky Memories. Add Jeff Walburn and something even more remarkable seems to happen.

I've doubted. I've doubted everything in the world surrounding me; all the negative, all the stand up sort of things too. I realized, through exercise of doing and putting out my real self… I had an epiphany really. You see, we are really just mirrors for each other. So ... so when someone you're with is sad, or happy, its' not just them but you. It changes when you're off by yourself.

I've doubted. I've doubted everything in the world surrounding me; all the negative, all the stand up sort of things too. I realized, through exercise of doing and putting out my real self… I had an epiphany really. You see, we are really just mirrors for each other. So ... so when someone you're with is sad, or happy, its' not just them but you. It changes when you're off by yourself.

"Back then, radio was on only a short time in the morning and then in the evening. Maybe news came on at 12. There was only one station, it was local, then regional, eventually national. As technology progressed, people became more aware of what could be done with it. At first radio was just entertainment, then advertising found a place on it, now it's used for everything.

"Back then, radio was on only a short time in the morning and then in the evening. Maybe news came on at 12. There was only one station, it was local, then regional, eventually national. As technology progressed, people became more aware of what could be done with it. At first radio was just entertainment, then advertising found a place on it, now it's used for everything. "Old Man Depression didn't start growing a full beard until 37 in the country where I was, we had an easier time than people in the city did I think. We could grow our own food. We did a lot to help each other, worked together as a community.

"Old Man Depression didn't start growing a full beard until 37 in the country where I was, we had an easier time than people in the city did I think. We could grow our own food. We did a lot to help each other, worked together as a community. While

While  "Here's what I think is the worst thing, the one line you hear from every person that doesn't try, "no one else is doing it". Like the guy who didn't even register to vote then tells you his political stand on everything, how he'd clean up the world if he were only president but he doesn't even mow the lawn."

"Here's what I think is the worst thing, the one line you hear from every person that doesn't try, "no one else is doing it". Like the guy who didn't even register to vote then tells you his political stand on everything, how he'd clean up the world if he were only president but he doesn't even mow the lawn." "And soon after, this commercial comes on for "American Idol". I know that, and the good things that preceded it and have come after, don't mean everything going to be great. It's actually harder when you try to live like that, by treating people right and doing what's right. People try to bring you down by truckloads.

"And soon after, this commercial comes on for "American Idol". I know that, and the good things that preceded it and have come after, don't mean everything going to be great. It's actually harder when you try to live like that, by treating people right and doing what's right. People try to bring you down by truckloads.

Immersion in such a unique culture, particularly in the home of masters' of its' music, was a rare and wonderful opportunity. Bert even showed me a thing or two on the banjo and I got to eat Bettys' corn-bread, (it is without equal in the world, and I've lived in VA, NC and KY – the capitols of the delight). Bert played not only with

Immersion in such a unique culture, particularly in the home of masters' of its' music, was a rare and wonderful opportunity. Bert even showed me a thing or two on the banjo and I got to eat Bettys' corn-bread, (it is without equal in the world, and I've lived in VA, NC and KY – the capitols of the delight). Bert played not only with  So, it was in this manner and under these conditions that I left Labor Day on the Jersey Shore in

So, it was in this manner and under these conditions that I left Labor Day on the Jersey Shore in  Spending time there was in a way like discovering a living Wild West ghost town – somewhat stuck in time but not in a closed-minded or limited way. Indeed, on the contrary, the people are far more intelligent, intuitive and talented than most I've known anywhere in the country.

Spending time there was in a way like discovering a living Wild West ghost town – somewhat stuck in time but not in a closed-minded or limited way. Indeed, on the contrary, the people are far more intelligent, intuitive and talented than most I've known anywhere in the country. So, when in Rome… I drank whiskey, shot at targets with a rifle, (and did a fair job of it), learned just what a crawdad was, got a few banjo lessons in between staring fixedly at the remarkable finger picking of every guitarist around, climbed a haystack or two. Hard to say which part of it was more fun.

So, when in Rome… I drank whiskey, shot at targets with a rifle, (and did a fair job of it), learned just what a crawdad was, got a few banjo lessons in between staring fixedly at the remarkable finger picking of every guitarist around, climbed a haystack or two. Hard to say which part of it was more fun.  And old-time has expanded and grown over the years, as have the towns and the people and musicians who live there. But up in the hills of Appalachia, playing music together is still a family routine, not much different from the way it was when my Grandmother described it. Musical families play in circles routinely. Children show interest in one instrument or another and are taught by a family member or someone in the community if the family doesn't have other musicians in it. They are, at first, allowed only to sit outside of the circle and try to keep up, (quietly). Once the child becomes good at rhythm, they are allowed to sit in the circle and play but again, quietly until they master it. Eventually, you wind up with a pretty good musician.

And old-time has expanded and grown over the years, as have the towns and the people and musicians who live there. But up in the hills of Appalachia, playing music together is still a family routine, not much different from the way it was when my Grandmother described it. Musical families play in circles routinely. Children show interest in one instrument or another and are taught by a family member or someone in the community if the family doesn't have other musicians in it. They are, at first, allowed only to sit outside of the circle and try to keep up, (quietly). Once the child becomes good at rhythm, they are allowed to sit in the circle and play but again, quietly until they master it. Eventually, you wind up with a pretty good musician.

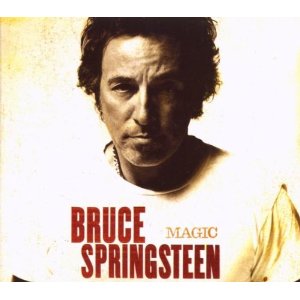

Sprinsteen has always sung about the everyday problems and situations of ordinary people, centered around his native South Jersey, both with the E Street Band and as a solo artist. His influences have, from the beginning, included Seeger, his band-mate

Sprinsteen has always sung about the everyday problems and situations of ordinary people, centered around his native South Jersey, both with the E Street Band and as a solo artist. His influences have, from the beginning, included Seeger, his band-mate  But its' a cool thing, not a creepy thing. People are very aware of him because he keeps in touch with them. He still practices in Asbury, makes impromptu appearances at the

But its' a cool thing, not a creepy thing. People are very aware of him because he keeps in touch with them. He still practices in Asbury, makes impromptu appearances at the

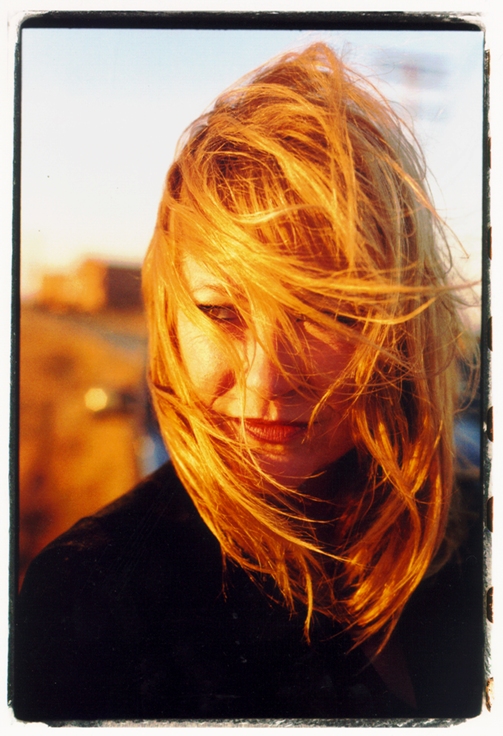

And so she began drawing the vivid characters of the Neo-Burlesque scene, soon joined them and then started an anti-art school, Dr. Sketchy's, now with branches in 13 cities and 5 countries. "They're very diverse." She said. "The one in Scotland was on BBC recently. All different sorts of things happen at them. One uses tableaux scenes. London is high-tea themed; each is influenced by the people running it and the theme around it. It's really taking off. They're in Finland, Rome and Berlin now too."

And so she began drawing the vivid characters of the Neo-Burlesque scene, soon joined them and then started an anti-art school, Dr. Sketchy's, now with branches in 13 cities and 5 countries. "They're very diverse." She said. "The one in Scotland was on BBC recently. All different sorts of things happen at them. One uses tableaux scenes. London is high-tea themed; each is influenced by the people running it and the theme around it. It's really taking off. They're in Finland, Rome and Berlin now too."  "I love how, onstage, you create an entirely different self in the same way you create a canvas." She said in a recent interview. "I love the power of being what you're not. I love how a good photograph doesn't so much as capture a moment as invent one a moment far more poignant and symbolic than the one when the picture was taken."

"I love how, onstage, you create an entirely different self in the same way you create a canvas." She said in a recent interview. "I love the power of being what you're not. I love how a good photograph doesn't so much as capture a moment as invent one a moment far more poignant and symbolic than the one when the picture was taken." It wasn't the Burton-esque perfumed garden she expected. "In Turkey, there was this place on the border I wanted to see a castle with arches, a weird fantasia with domed stropped turrets still crumbling. I went there and I couldn't believe it the gov't had hideously restored it buy putting on plastic roof architecture - horrifying sort of like a McDonald's roof –

It wasn't the Burton-esque perfumed garden she expected. "In Turkey, there was this place on the border I wanted to see a castle with arches, a weird fantasia with domed stropped turrets still crumbling. I went there and I couldn't believe it the gov't had hideously restored it buy putting on plastic roof architecture - horrifying sort of like a McDonald's roof –

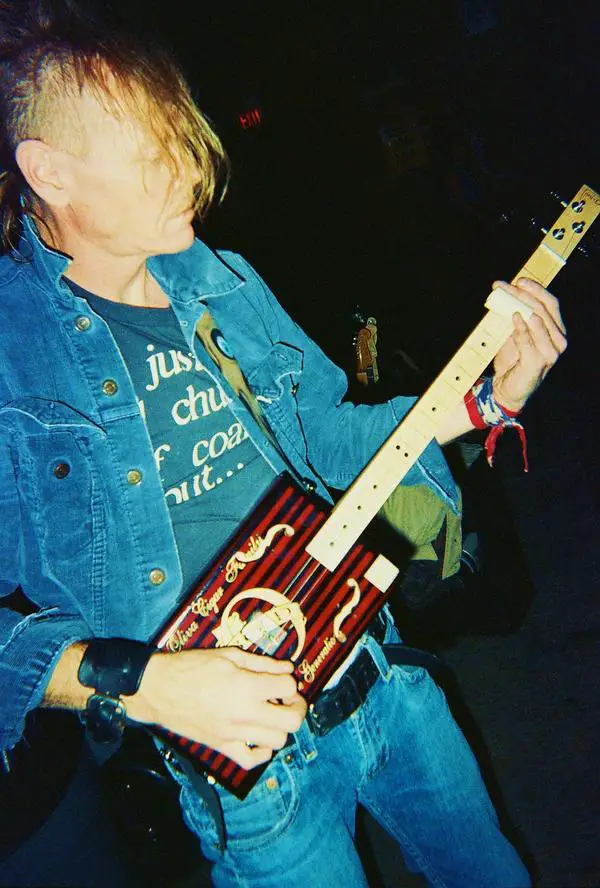

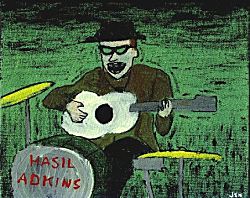

Through his music, Rockabilly was rounded out, (he's named, along with Elvis, as a "book-end" of the genre), the first, (and subsequent) rounds of Punk were heavily influenced and Psychobilly was born.. The odds of this happening would have been, for the average person, insurmountable.

Through his music, Rockabilly was rounded out, (he's named, along with Elvis, as a "book-end" of the genre), the first, (and subsequent) rounds of Punk were heavily influenced and Psychobilly was born.. The odds of this happening would have been, for the average person, insurmountable. "Hasil truly lived his persona yet he would have been the first to say that nobody could sustain that over the top psychobilly mindset all the time." Smith said. "One interesting thing about him was that he contained a lot of duality. It wasn't so much contradiction as duality. There were a lot of ironic things about him that didn't make sense at first, but as you got to know him they came together. He didn't have much formal education but was a complete news junkie that read and studied politics all the time. He loved discussing politics and current events as well as hunchin' and the glories of fried chicken."

"Hasil truly lived his persona yet he would have been the first to say that nobody could sustain that over the top psychobilly mindset all the time." Smith said. "One interesting thing about him was that he contained a lot of duality. It wasn't so much contradiction as duality. There were a lot of ironic things about him that didn't make sense at first, but as you got to know him they came together. He didn't have much formal education but was a complete news junkie that read and studied politics all the time. He loved discussing politics and current events as well as hunchin' and the glories of fried chicken." "He was fearless. When he went on stage he didn't give a damn if you liked him or not, he was there to party and ROCK the joint. He wanted you to have a good time but it wasn't all about ego or trying to be cool. He was just having a good time and raising hell.

"He was fearless. When he went on stage he didn't give a damn if you liked him or not, he was there to party and ROCK the joint. He wanted you to have a good time but it wasn't all about ego or trying to be cool. He was just having a good time and raising hell. "She said, "No, honey. I ain't gonna tell you what to do when you get there but take your guitar."

"She said, "No, honey. I ain't gonna tell you what to do when you get there but take your guitar." Possibly in part from that, but largely due to Hasil, Smith is now a performer too after many years of playing at home or "woodshedding it" as he calls it and has started taking to the stage with his own one man band incarnation CuzN Wildweed.

Possibly in part from that, but largely due to Hasil, Smith is now a performer too after many years of playing at home or "woodshedding it" as he calls it and has started taking to the stage with his own one man band incarnation CuzN Wildweed. "I'd played it there before and done some pretty weird shit and never had a problem. But one night I pulled it out and dared the audience for me to plug it in. I did a song I made up on spot and halfway through the owner came running up screaming that I had to either turn it down or he was pulling the plug. After the set he said, "Cuz. you're welcome back here, but I don't want to ever see that thing in my bar again!"

"I'd played it there before and done some pretty weird shit and never had a problem. But one night I pulled it out and dared the audience for me to plug it in. I did a song I made up on spot and halfway through the owner came running up screaming that I had to either turn it down or he was pulling the plug. After the set he said, "Cuz. you're welcome back here, but I don't want to ever see that thing in my bar again!"

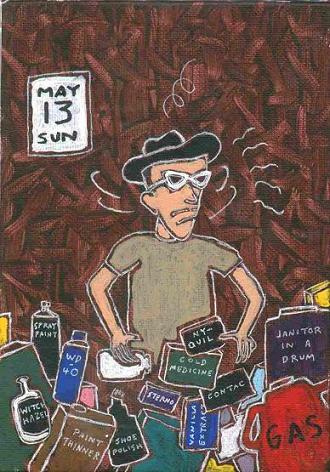

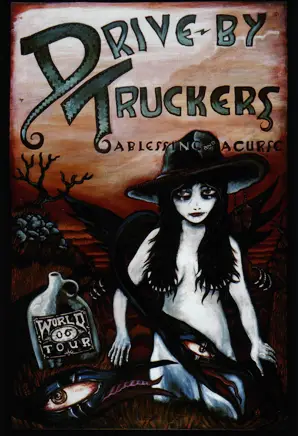

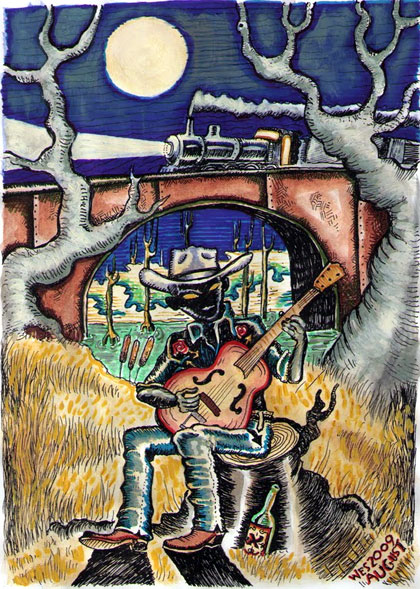

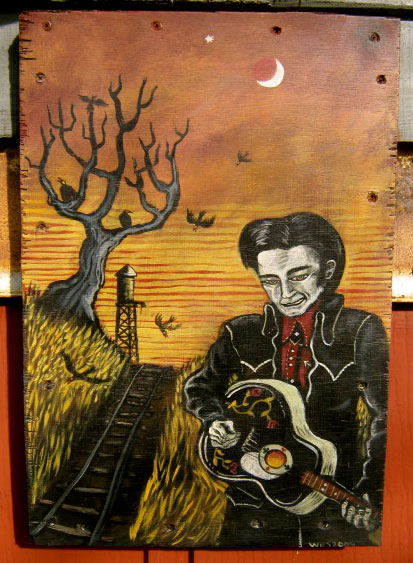

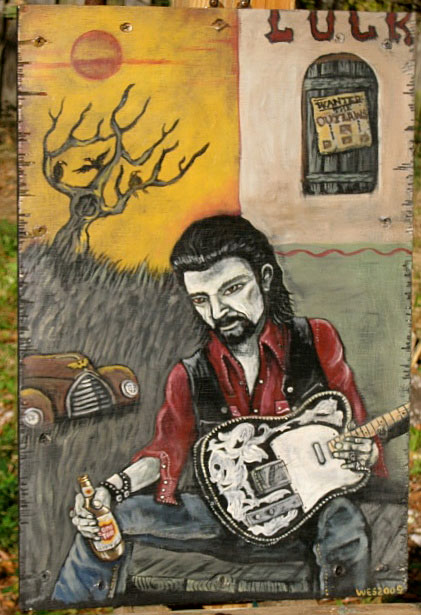

WF: The songs, like the paintings, deal with moonshine, ghosts, lonesome roads... there's a tavern song written from the vantage point of a dangerous man before he got all big and dangerous, when he was a bum out roaming around not having any place to call home, living on the road... one I wrote about moonshine while watching 'The Sopranos', about how the moonshine industry is a family sort of thing and nobody talks out of turn or you just disappear somewhere in the swamp... it is kind of like 'The Sopranos', when a brother turns rat, no questions asked, just an empty spot in the pew Sunday morning. It's the dark side of things but it's an explanation of why it is what it is.

WF: The songs, like the paintings, deal with moonshine, ghosts, lonesome roads... there's a tavern song written from the vantage point of a dangerous man before he got all big and dangerous, when he was a bum out roaming around not having any place to call home, living on the road... one I wrote about moonshine while watching 'The Sopranos', about how the moonshine industry is a family sort of thing and nobody talks out of turn or you just disappear somewhere in the swamp... it is kind of like 'The Sopranos', when a brother turns rat, no questions asked, just an empty spot in the pew Sunday morning. It's the dark side of things but it's an explanation of why it is what it is. GW: What, I asked him, did you want to be when you grew up?

GW: What, I asked him, did you want to be when you grew up? WF: That truck is almost a shrine now, still full of the things that were in it the day he died, like an old corn shucker with “The Boss” engraved on the bottom, Lucky and Camel packs, receipts going back to before I was born. I used to go sit in it every day and pretend I was driving (laughter). One day, the truck disappeared. I asked my parents what happened to it and they suggested I call the Sheriff, he laughed again, turned out they’d gotten it running for me for my birthday. They forgot to flush the radiator though; it never drove right after that.

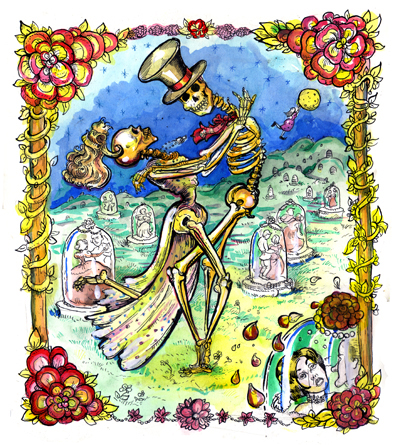

WF: That truck is almost a shrine now, still full of the things that were in it the day he died, like an old corn shucker with “The Boss” engraved on the bottom, Lucky and Camel packs, receipts going back to before I was born. I used to go sit in it every day and pretend I was driving (laughter). One day, the truck disappeared. I asked my parents what happened to it and they suggested I call the Sheriff, he laughed again, turned out they’d gotten it running for me for my birthday. They forgot to flush the radiator though; it never drove right after that. WF: Both the dark and light of it are reassuring to me. Beautiful is a subjective term. I see it as a paradise. When I was a kid, the idea of the Sunday school version of Heaven scared the Hell out of me. No dead trees? No old cars? No rust or broke down old barns? That didn't sound like Paradise to me.

WF: Both the dark and light of it are reassuring to me. Beautiful is a subjective term. I see it as a paradise. When I was a kid, the idea of the Sunday school version of Heaven scared the Hell out of me. No dead trees? No old cars? No rust or broke down old barns? That didn't sound like Paradise to me.

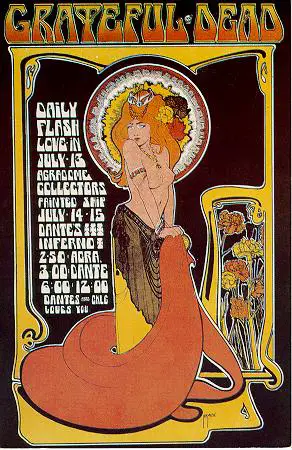

Throughout the early to mid 60s, an art movement was building in San Francisco. Masse described going there every two months ago, staying with the

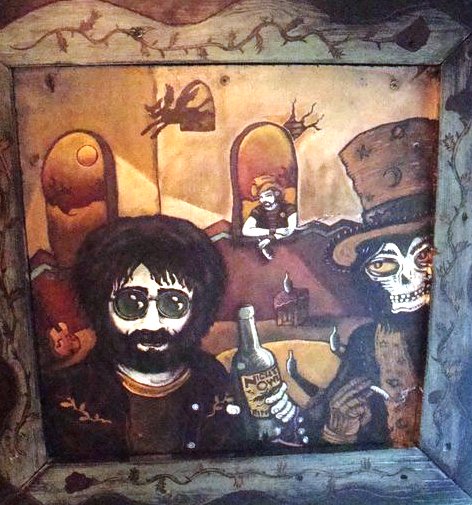

Throughout the early to mid 60s, an art movement was building in San Francisco. Masse described going there every two months ago, staying with the  BM: I went down to do a cover for Warner Brothers. It was the first time I got to watch an album being recorded and was really exciting. When I got there, they told me there was someone else from Canada they wanted me to meet. Here comes skinny blonde, all teeth with two guys. At the time it was no big deal; nonetheless, it was Joni Mitchell, David Cassidy and Graham Nash.

BM: I went down to do a cover for Warner Brothers. It was the first time I got to watch an album being recorded and was really exciting. When I got there, they told me there was someone else from Canada they wanted me to meet. Here comes skinny blonde, all teeth with two guys. At the time it was no big deal; nonetheless, it was Joni Mitchell, David Cassidy and Graham Nash. BM: There was a renaissance going on that mirrored itself in the Hippie movement. Art mixed with psychedelic drugs, the colors were bright instead of organic. It's similar to the parallel group of young, rebellious guys, the Impressionists. They would quietly go into their little studio, paint away at something, then go drink absinthe.

BM: There was a renaissance going on that mirrored itself in the Hippie movement. Art mixed with psychedelic drugs, the colors were bright instead of organic. It's similar to the parallel group of young, rebellious guys, the Impressionists. They would quietly go into their little studio, paint away at something, then go drink absinthe.