Although there’s no camping at Bumbershoot, the crowd looks funkier than yesterday. I pass many familiar faces strolling around Seattle Center; they may be reapplied with make-up or flourished with new clothes, but no amount of blush can mask the wear and tear of an all-nighter. I get the sense that, even if it wasn’t 80 degrees and sunny, people would still be wearing their shades.

There’s an interesting catch-22 when it comes to music festival etiquette: while debauchery is expected, recovery time is respected. Weekend pass holders are so keen on putting up this front – this appearance of being unphased by the previous day’s events – that they forget the most obvious signs: a limping left leg, a lost appetite, a throbbing eardrum. The true Bumbershooter goes all-in Saturday night and comes back Sunday morning…playing the very same cards.

It’s early afternoon and I head over to Key Arena (the main stage, which holds around 17,000) to check out Broken Social Scene. While this Canadian baroque-pop band is adamantly against the label “supergroup,” it’s hard to dispute their track record. I mean, come on: they’ve got more spin-offs than Cheers. Without Broken Social Scene, renowned acts like Feist and Stars wouldn’t even exist.

It’s been ten years since founding members Kevin Drew and Brendan Canning released their mostly-instrumental debut Feel Good Lost, yet it seems the band has actually gained momentum with age. A self-dubbed “musical collective,” Broken Social Scene has performed with everything between six and nineteen members.

I arrive at Key Arena a few minutes early and am able to snag a spot right up against the stage. Looking around, I get anxious about the abundance of pre-college teens filling the floor: has Broken Social Scene jumped the shark? The kid next to me shows his age (or lack thereof) with a patchy mustache, so I’m taken aback when noticing he’s covered in tattoos and – brace yourself – has a drooping hole in his ear where a gauge should be (GROSS!)

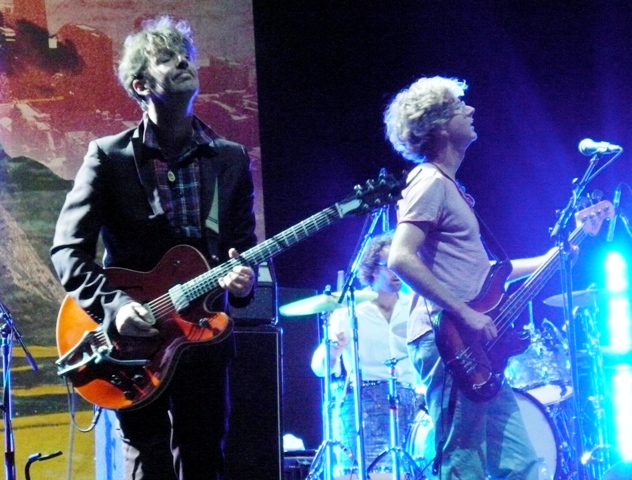

The proceeding hour and a half slaps me in the face as cold, hard evidence that Broken Social Scene is still one of the best live acts around. From the moment their current lineup – which consists of nine members – walks on stage, this band is captivating. Their set opens with an instrumental that displays lead guitarist Andrew Whiteman’s mastery of tone and effects. His orange Gretsch can somehow transform into a gentle harp, a soothing viola, or a gritty Telecaster with the click of a foot switch. And it’s not just Whiteman’s notes that enchant; his stage presence is at once enormous and personal. It’s the type of honed performance one can only achieve after years of experience.

In fact, the whole band captures this very same charisma: they’re playing to a full arena while simultaneously connecting with each individual attendee. Although Broken Social Scene mellows out on their ambient tunes, they jump, kick, laugh, and dance when playing upbeat songs. Drew is by no means the strongest lead vocalist of the festival, but it hardly matters when backed by complex harmonies, oscillating guitars, throbbing keys, and the occasional trumpet or saxophone.

As if they weren’t killing it already, Broken Social Scene scores big with the Seattle crowd by covering Modest Mouse’s “The World At Large.” They close the set with a couple of crowd-pleasing older tunes, and when the Key Arena house lights are turned back on I see that the whole venue is filled with big grins and dropped jaws. This was hands down the most energetic, charismatic performance of Bumbershoot.

I spend the late afternoon sitting by The Fountain, listening to the clashing echoes of performances from nearby stages. The auditory cocktail of flowing water, laughing children, and distant guitars brings me to an ephemeral, somewhat spiritual place. I luckily snap out of this trance just in time to catch Leon Russell at the Mural Stage.

I spend the late afternoon sitting by The Fountain, listening to the clashing echoes of performances from nearby stages. The auditory cocktail of flowing water, laughing children, and distant guitars brings me to an ephemeral, somewhat spiritual place. I luckily snap out of this trance just in time to catch Leon Russell at the Mural Stage.

At 69 years young, Russell has all but solidified himself as one of America’s greatest songwriters. He’s played with everyone from Joe Cocker and J.J. Cale to Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson, Eric Clapton, Frank Sinatra and Doris Day (and that’s just scratching the surface!) He’s been sideman and frontman, has written number one hits, and is in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Perhaps my favorite part of Russell’s resume is his nickname: “Master of Space and Time.” I’m not sure how one goes about obtaining such a title, but he’s certainly filled into the role. At this point in his life, Russell looks exactly like a five year-olds’ image of God – long white hair, long white beard, a slow speaking voice, and a limp that insinuates wisdom rather than weakness.

Leon Russell’s trademark is putting together exciting medleys of covers and original tunes at his shows. With a great backing band – featuring Chris Simmons, the best blues-rock lead guitarist I’ve heard in a long time – Russell’s set was outstanding. Among the covers he played were “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” “Wild Horses,” “I’ve Seen a Face,” “Georgia On My Mind, “Great Balls of Fire,” and “Roll Over Beethoven.”

Day three at Bumbershoot paled in comparison to Saturday and Sunday. At this point in the weekend, attendees looked like they were moving at half-speed. Shuffling feet struggled to lift off the ground, and audience members that had been dancing against the stages now opted to watch shows sitting down on blankets.

I for one spent much of the day in the pressroom, collecting my thoughts and envisioning all these Seattleites back at their day jobs early the next morning. It won’t be long before we’re sitting at our desks, complaining about the lack of sun or arguing over whose got the best happy hour in Belltown.

But this review won’t be complete unless I address the elephants in the room: Daryl Hall and John Oates. They’ve sold 60 million records throughout a career that has spanned decades and genres. There’s no debating that, as the biggest band, they should be closing Bumbershoot. That said, I was pretty disappointed by their two hour set. Sure, they played all the hits. And sure, they had a great band. But they had such negative chemistry – such competing egos – that it was hard to focus on anything but their despicable personas.

Looking back I actually begin to hate Hall and Oates’ closing performance: compared to the excitement of a breaking band in Pickwick, compared to the transience of Vetiver, compared to the charisma of Broken Social Scene, these guys are like watching rocks fossilize. Even Leon Russell – who’s got quite a few years on Hall and Oates – was captivating and lively.

Oh, and game, set, match: no mustache.

-