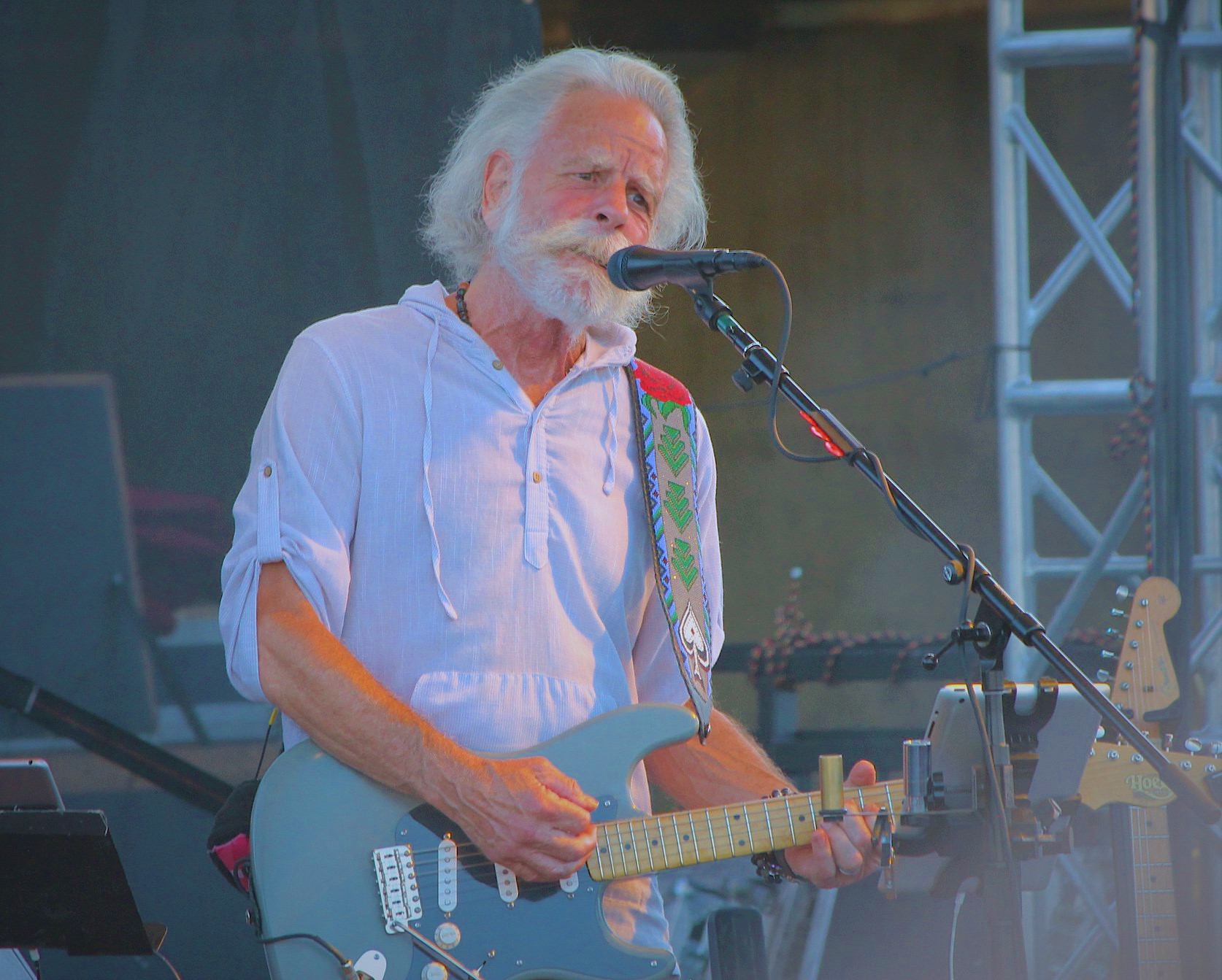

GW: Dylan Muhlberg of Grateful Web here. I am thrilled to be joined by two men whom I admire very much. Tom Constanten’s professional career began as a member of the Grateful Dead in the band’s early developmental years. His impressive solo career and collaborations on dozens of other albums make him an important fixture in American music. Bob Bralove worked as a piano tech for Stevie Wonder before bringing the Grateful Dead electronic technology that would change the band’s sound from then on. The two continue to collaborate on dual pianos with their longtime evolving project Dose Hermanos, and are celebrating the release of their new album Batique. Thank you for joining me this afternoon guys.

BB: Good to be here.

TC: Very Sweet.

GW: Likewise. Your collaborations as Dose Hermanos date back to 1995. How did you two come to play together and realize your strong musical chemistry?

TC: When we lost Jerry, we realized we had to do something. Continuing the music, especially with that wild style of improvisation seemed to be the way to go. It was a magic carpet that we’ve been riding on ever since.

BB: For me, I had been coming out of the tech world, and felt that I hadn’t quite owned my place as a player. But when Tom said the way to get through this is to play, I realized that he was right. And then when dug in. The early sessions were quite amazing for me. [Laughs] I had this little bottle of crystal mescaline that someone; I think [Ken] Kesey had lost in the floorboards of the Grateful Dead’s studios. And as we left someone handed it to me and said, “Do you want this?” And I was just beginning my psychedelic adventures then, and Tom was my guide. And I couldn’t have asked for a better one.

GW: [Laughs] That’s a crazy story. Didn’t know about any of that. Tom played piano and synthesizers with Grateful Dead in the late 1960s. Bob came to the band in mid 80s and brought them MIDI technology, infinitely widening the band’s musical possibilities. Though both of you were involved in different eras of Grateful Dead music, how have your individual experiences with that band brought you to a closer musical understanding?

TC: You know we sort of bookend the Grateful Dead; me towards the beginning and Bob towards the end of the ride. And that’s one of many apparent connections. It seems as we continue these explorations we discovered a vast number of other connections, musically, culturally, otherwise. Our intuition and connection as we play is telepathic.

BB: I think that the Grateful Dead thread that pulls through our experience is the understanding that the kinds of pieces that we want to do our achievable through improvisation. Sometimes we do something that seems to me as clearly defined as an orchestral piece, like every note was written. And yet, we’re doing it completely improvised, and being able to trust that improvisational sense is something Tom certainly helped the Grateful Dead flush out, and was a big part of my experience with the Grateful Dead.

GW: Well put. The new album is often gorgeous and daunting simultaneously. All of the compositions and textures were created on grand pianos, no distortion or effects. What inspired your change of direction with the Batique album?

TC: Well real pianos are where we both come from. Electronic is an understanding as well. We know about it, and like it, and enjoy it. There’s something organic feeling about the 18th century technology that I for one feel like I can just cut loose and fly freely with.

BB: For me it’s also that when you’re playing the grand piano, the limitations sonically, become this place of infinite expression. No longer are you thinking about the sound or the orchestration in a different way. It’s all in your fingers; it’s all in the touch. If you want to make it moody, you feel it, and you play it that way. It’s all in the fingers and how you express yourself. It’s not in the processing; it’s not in the thought about it. It’s in the expression of it. Very immediate. I think it seemed like it was time to go in that direction for us. It’s a place that we both experience, like when Tom comes and hangs out at my place. I have my dad’s old Steinway Grand. We listen to each other play new material. We sometimes sit at it side-by-side and bang some new idea out. It’s always been part of our repertoire but kind of difficult to pull off in the recording situation. Part of it is just logistics. It’s hard to find a place with two pianos. And we found one. Though the pianos were in different studios and had to be wired together, we still had the opportunity to do it so we just went for it.

GW: The recording is testament to that success. Leaving only the music to guide itself. How was it recording this way? Did it flow effortlessly regardless?

TC: This is, I think our fifth CD, and we’re well familiar and comfortable going out onstage without a set-list or chord charts, occasionally minimal one or two word preparation. We got used to diving deep into that musical gene pool.

BB: This kind of music is so intensely improvisational that we always know there’s going to be some sort of obstacle that we’re going to turn into an opportunity because it becomes something that we respond to. I, being the sort of tech producer, worrier. I was worried about whether we’d be able to see each other for cues. And on the first take those worries just evaporated. The first take I could hear Tom breath, I could hear that we were one right away just from the sound. I knew we were off to a running start. So it was just like, boom! No worries.

GW: Listening again and again to the album and having seen Dose Hermanos a couple of years back when you were in Denver it was a diverse experience to hear the sound that came out of this particular recording.

Because of the acoustic nature of the grand piano, some of the album’s sound comes off as classical first and psychedelic second. Was this something that was conceptually understood before recording or did it evolve into that?

TC: We don’t see boundaries or classifications. We see connections. And sometimes certain sounds come from different projections. Some of it could sound classical, but it might sound like country, or like Jerry Lee Lewis rock ‘n’ roll. We’re reaching for all those things.

BB: We are sort of in a time that everything is getting categorized in an extreme amount. It almost seems to be about the shopping experience. How things are categorized. The techno musical world/electronic dance music comes up with a new term for something every few weeks. It’s like creating new categories that can often seem like separating things. Is this classical? Is that whatever? We’re at a point in our cultural history where all of these things will eventually just evaporate, and hopefully people will start enjoying music they love no matter where it comes from. I think you see this in some of the kinds who have grown up with the Internet as their source of music. Everything is available to them. We’re kind of the old generation of that but everything is available for us to play. So it all becomes the same expression of us, but sometimes we’re referencing Stravinsky, sometimes were referencing Jerry Lee Lewis. It’s all Dose Hermanos to us.

GW: It’s all on the table. The finished product is a richly diverse collection of tunes. Each of your strong individual backgrounds in theory and classical understanding of composition helped build coherence in the avant guard. Who are some of your favorite musicians who have furthered free and avant guard music?

TC: I got into the avant guard very young. I was so much into it that I went to Europe to study the music of Schoenberg and Charles Ives. Later on I got to meet Earl Brown and John Cage. Then back at home I continued to discover this world that reveals infinite possibilities. And that carries over to the Dose Hermanos realm.

BB: Yes, and certainly for me, that has been in the classical world with John Cage, George Crumb. I studied with Wayne Peterson, a Pulitzer Prize Winner. I did some major study in the compositional world but also I was very influenced by the Art Ensemble of Chicago. And even stuff like Funkadelic and George Clinton. The stuff they were doing at the time was mind-blowing. Everything that was happening. It was a time that you could hear things on the radio that would range from Frank Zappa, I mean there was a station in the early 1970s in San Francisco, that would move from Mozart to John Lennon in one deejay. He’d have the guts to connect all of that music. It was an adventurous time for your ears. And I think that both Tom and We were sort of absorbing whatever we could. It was so stimulating and exciting. It was everywhere. In the radio waves. In coffee houses. There were lots of people doing music. I mean look what was happening with the Grateful Dead and Miles Davis. It’s amazing.

GW: It was definitely a time of expression in music in the U.S. and the whole world.

The names you chose for these titles are imaginative in a very functional way. I love how it gives the listener an impression or something to relate to when listening to them. Did you two invent the song titles together after the compositions were performed? Is there a larger thematic vision?

TC: Sometimes it’s before, sometimes it’s after. The titles serve as a secret entry to the piece, where you have a certain view. Often as few of words as possible. It will give you a clue as to what to listen for what to look for. And even your response to that clue could be different that we thought and that’s valid too.

BB: The secret key is good. I’ve never heard you use that before Tom [Laughs], but its really good. It’s one of those things when the title comes up for us, we both know its right. The only power that one of us has if Tom has an objection to a track because of the way he played, I can veto that If I loved the way he played. And he has the same option. So your ego is not allowed to overshadow Dose Hermanos. But most of the time we know exactly what needs to be done. We just stand out of the way and it happens. It’s really amazing this sort of psychic connection that we have structures everything. We’ll sometimes look at an option for a way to do it, and we’ll both look at each other and say,“That’s not Dose, is it?” And we’ll look for something else.

GW: And that’s the connection again. The song titles reminded me of the song titles from the 1991 Infrared Roses release.

BB: We’ll that’s an honor and I appreciate you saying that. [Robert Hunter] He’s an idol of mine.

GW: And he [Hunter] wrote the track names for Infrared Roses?

BB: Yes he did.

GW: So I wanted to ask both of you individually about order in chaos when it comes to approaching music.

Tom, you have collaborated with generations of different gifted improvisational driven musicians. Though your catalogue features brilliant compositions and originals, you seem to thrive in the spontaneity of musical creation. Is there order to be found within the chaos?

TC: I wonder if the question might be is there such a thing as chaos? Because whenever I try to find order, all I do is look harder and I saw something that was integrating everything that was going on that made sense. Henry Miller said coincidence is a word to describe an order that we don’t yet understand. And I just keep trying to push out my understanding. In practical terms, in playing together over the last decade and a half or more, we finally just evermore relaxed; get into the space where we know the result will come out nice. At first it was kind of experimental. Sometimes it would come out better than other times. Now, we can pretty much rely on it. So, making order out of chaos? Maybe it’s making chaos out of the order.

GW: Thank you Tom.

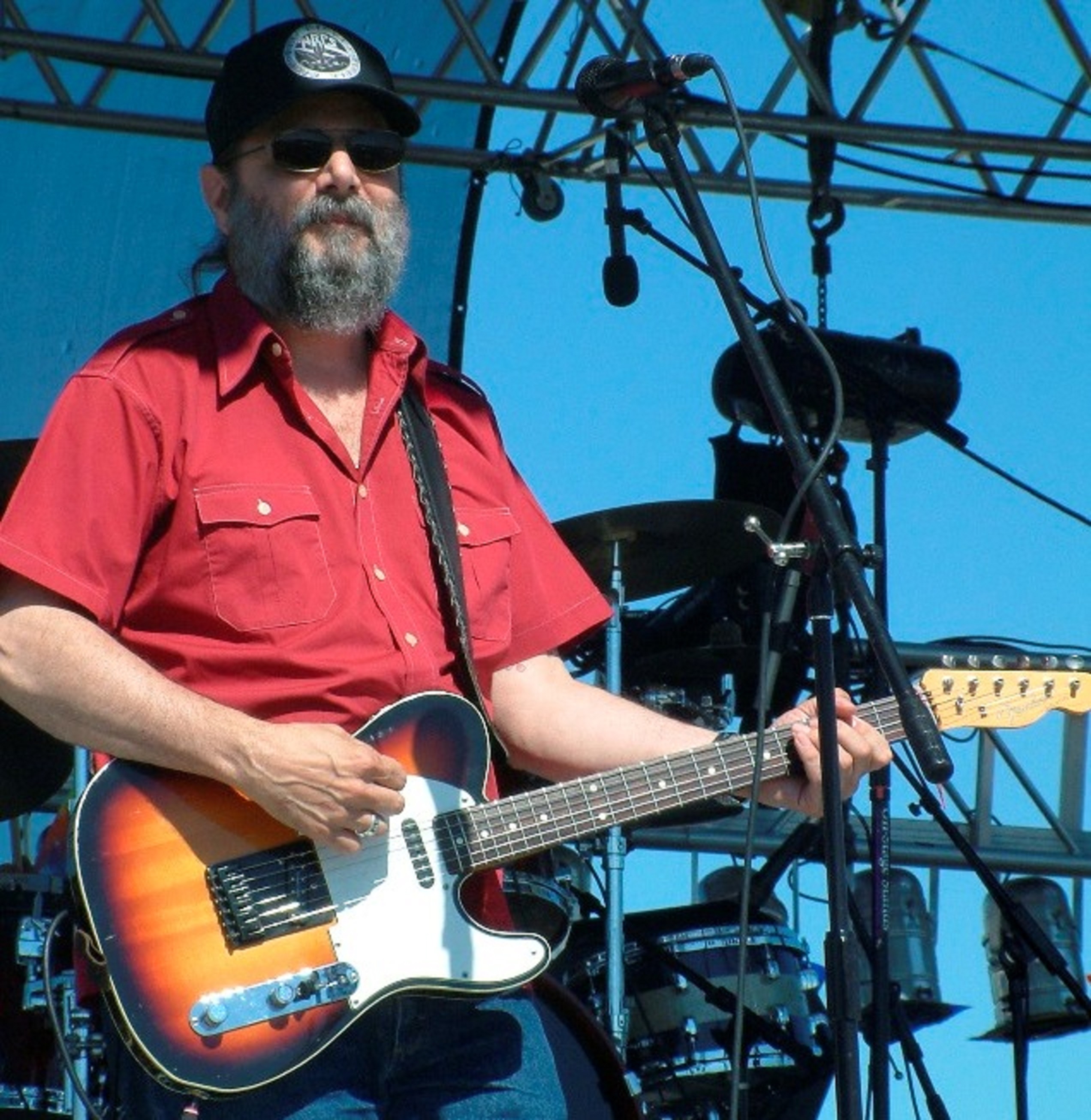

Bob, your contributions to Grateful Dead extended into their jam and drum segments in the second set. This was, at the time, the truly 100% improvised part of every Dead show. Did copiloting and experimenting with the Rhythm Devils bring you a deeper understanding of creating order in chaos?

BB: Yes. Of course it did. Both what could happen with the drums, the segway into the space section, then playing with the guys in space a little bit before they would take over was incredible instructional. Those guys were and still are absolutely brilliant. Their intuitive understanding of what to do and how to approach it was instructional at every show. It gives you an understanding of the power of commitment. To play a line with intent commitment, and to respond with somebody else’s line with commitment is a huge step toward making things work. And also, understanding the structures that were in the other parts of the show, and the eagerness to abandon that. You know, I still write songs. I was lucky enough to write songs with Bobby [Weir] and Vince [Welnick]. Those were instructional aspects too. This improvisational thing, of understanding that you could jump off the cliff and enjoy the ride down whether you were going to land on a feather bed or rocks was a wonderful instruction.

GW: Certain compositions from the album seem like they could be rehearsed or reworked and possibly performed live at Dose Hermanos shows. Had you put any thought it to performing any of these tracks live when its time to tour?

BB: Well, we just came off of a tour and we were performing some of them. It’s part of what we do. If we create something, learn it, and then integrate it, its another piece of Dose Hermanos.

TC: And I should also add that the Grateful Dead never performed a “Dark Star” the same way twice either. They would never go to the same place. And that’s what we’re like. We may go to the same musical pieces, but never the same.

BB: Sure. We’ll explore an idea, and maybe the next time we play that tune, that idea is different. Maybe its because the audience is different or we feel differently. Maybe its just time for a new take. Somebody plays one note and the other person goes, “Ah’ha!”

GW: We’ll I cant wait until your next Colorado appearance. That is all the questions I have for you this afternoon. I wanted to wish you warm congratulations on the new album and continuing your long-time collaboration. No doubt those with open minds will be moved by this music. It’s been a great honor to talk to both of you. I’m 26 years old and never personally saw the Grateful Dead, but their music has helped shape me as a person, and you are both part of that, so I thank you.

TC: Thank you for your time Dylan.

BB: Thank you.