I was twenty-four, a couple months out of college, manning the phones at my first real job in New York City. The owners were in L.A. for a conference, which meant I had the whole place to myself—just a swivel chair, a humming computer, and a window that didn’t open. It felt like adulthood in miniature: hold down the fort, answer professionally, don’t screw up.

I checked the Dead message board when I got in—back then it was a spartan list of links and comments, nothing fancy. Grateful Web had blinked online a few weeks earlier, but for breaking Dead news you still hit the board. Nothing much there at 8 a.m. NYC time. I made some tea, Earl Grey, hot. Tried to look busy for no one.

Then I heard the Dead on the radio. One of the classic rock stations—WNEW? WPLJ?—I can’t remember which. Switched to another station: the Dead again. That’s when the room got a little colder. I clicked back to the board and the screen had exploded—forty, fifty new posts, a chorus line of shock:

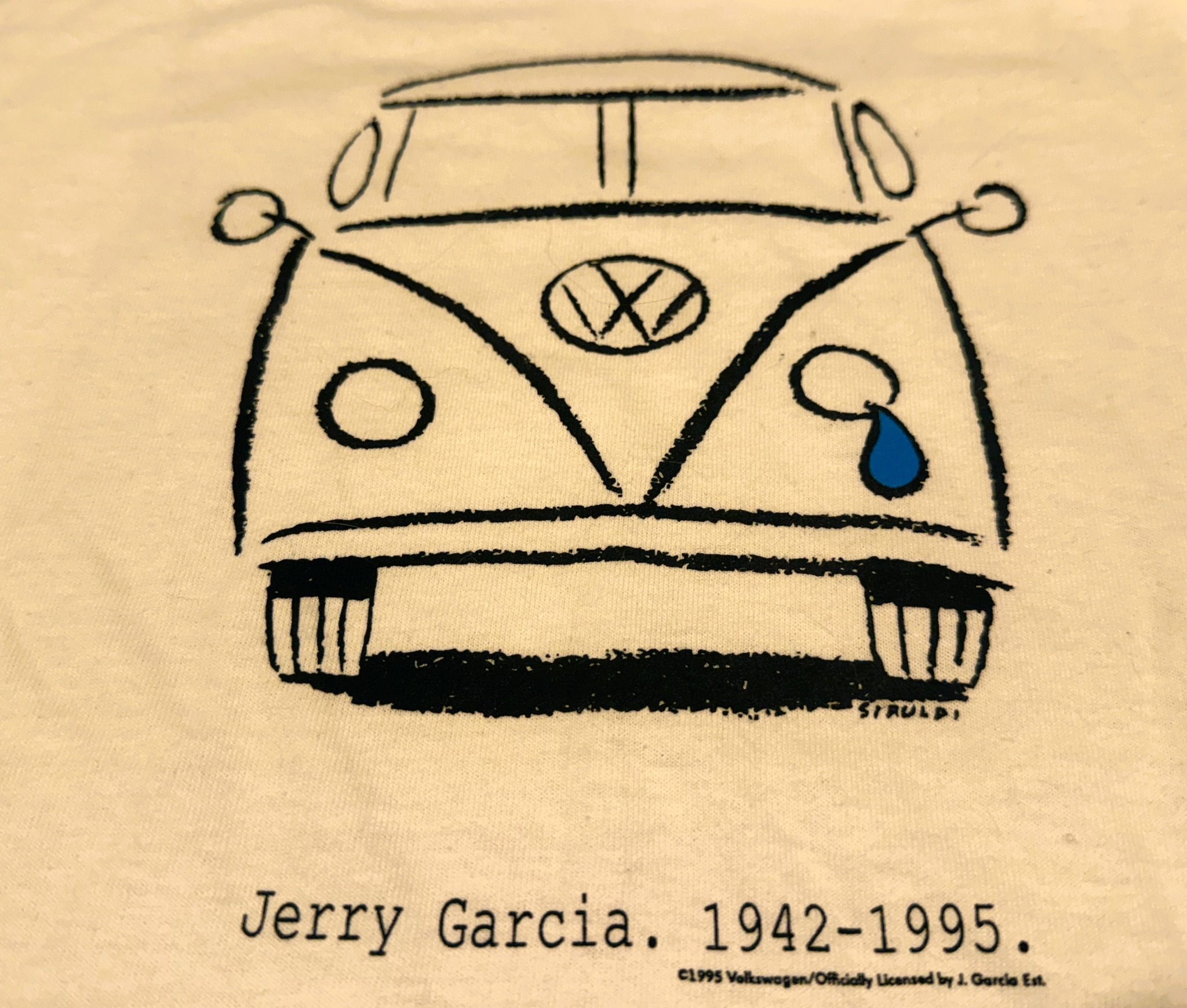

“Jerry’s dead.”

“Jerry just died.”

“Oh my god, Jerry is dead.”

“This is real.”

My hands started to shake. I went back to the radio. The DJ confirmed it in that practiced, steady tone they use for terrible news. And that’s when the tears started. Not a mist, not a discreet dab with a sleeve. I mean heaving, gut-punch sobs. I’ve never cried harder for anyone in my life.

The phone rang and I snapped back into “professional,” but the second I heard a familiar voice—family—my composure blew apart. I was bawling at my desk, alone in a Manhattan office that suddenly felt like an empty church. More calls came. Each one was love and confirmation, and each one unspooled me again.

Eventually the boss called from the West Coast, sleepy and stunned. “Go home,” they said. “We know the shape you’ll be in.” I locked up, walked out into that hot, indifferent city, and found the bus to Wyckoff. I fought the tears the whole ride, losing most rounds. I remember pressing my forehead to the glass, watching New Jersey blur, thinking: this can’t be the world I woke up in.

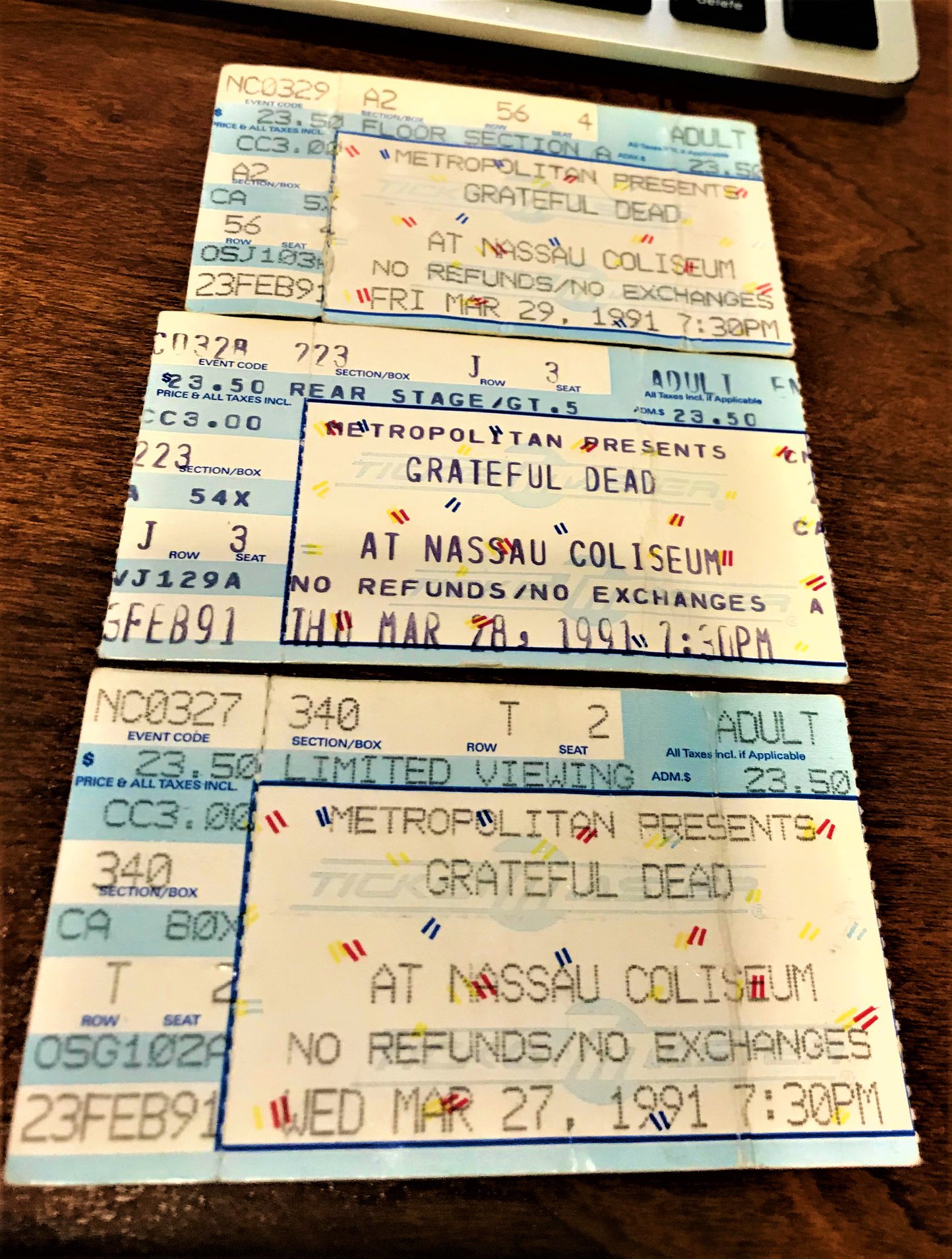

Home was me and my dog, Norton. Bless that dog. I took bong hits and cried, then hugged him and cried harder. More calls. More crying. Grief came in waves: friends, family, road stories, bootlegs, what he meant, what he gave, everything we’d taken for granted that was now suddenly, permanently fragile.

In that blur of days, my mom’s sister’s husband—technically my uncle—died too. Maybe a day later, maybe the same day; it all smears together now. I went to his wake, eyes still raw and ballooned from crying for Jerry. My cousin, his daughter, looked at me and said something like, “Mike, I didn’t realize this would hit you so hard.” She thought I was shattered by our uncle. And I loved my family, but the truth was I’d been wrecked for days already. Grief stacks like that—messy and unfair—and there I was, carrying one loss into a room built for another.

That night I put on 4/16/83—“Black Peter”—and it absolutely flattened me. There’s a certain kind of crying that cleans the corners you didn’t know were there. That was it. I don’t consider myself religious. I’m a proud atheist, still am. But sometime past midnight, after the last walk with Norton, something happened I’ve never forgotten.

The moon was bright—the kind of white, quiet light that makes edges crisp. I was walking back up the driveway, and the way that moonlight hit the bark of a tree, I swear I saw Jerry’s face. Not a trick of shadow I talked myself into, not a forced comfort. It was just… there. He looked happy. He looked at peace. And for a breath or three, so was I.

I know what grief can do to a mind. I know how the brain looks for patterns that the heart can live with. Maybe I was delirious from a day of tears. Maybe it was just bark and light. But the feeling was real: not that Jerry was somewhere he hadn’t been, but that the love and the music had weight in this world—and would keep having weight, even without the person who started the ripple.

The next morning, the world had not ended. The sun came up, the buses ran, and work was still work. But everything had shifted a few degrees. You could feel the community turning toward each other, building something out of shared loss—tape trees, message boards, backyard memorials, long drives and longer nights. We learned how to keep a flame without the match. We learned how to sing to each other when the singer was gone.

Thirty years later, I can still hear the radio announcement in that sterile office. I can still feel the bus window against my forehead. I can still smell my dog’s fur and the way my chest hurt after “Black Peter.” I can still see my cousin’s face at that wake, wondering why I looked so wrecked. And I can still see that moonlit bark, calm as a benediction I don’t believe in.

Maybe that’s the point. You don’t have to believe in anything for the music to find you. It already did. It keeps doing it. Every time a song catches a stranger in the ribs. Every time an old tape makes someone new. Every time a crowd sways as one and a guitar line threads them together, subtle as breathing.

He’s gone. We know that. But the thing he helped build—what we built with him—didn’t end on August 9, 1995. It kept traveling: speaker to skull, porch to porch, venue to venue, memory to memory. And on a good night, if the moon is right and the music is honest, you can still catch a glimpse of him in the bark. Happy. At peace. And still here, somehow, in the only way that ever really mattered.