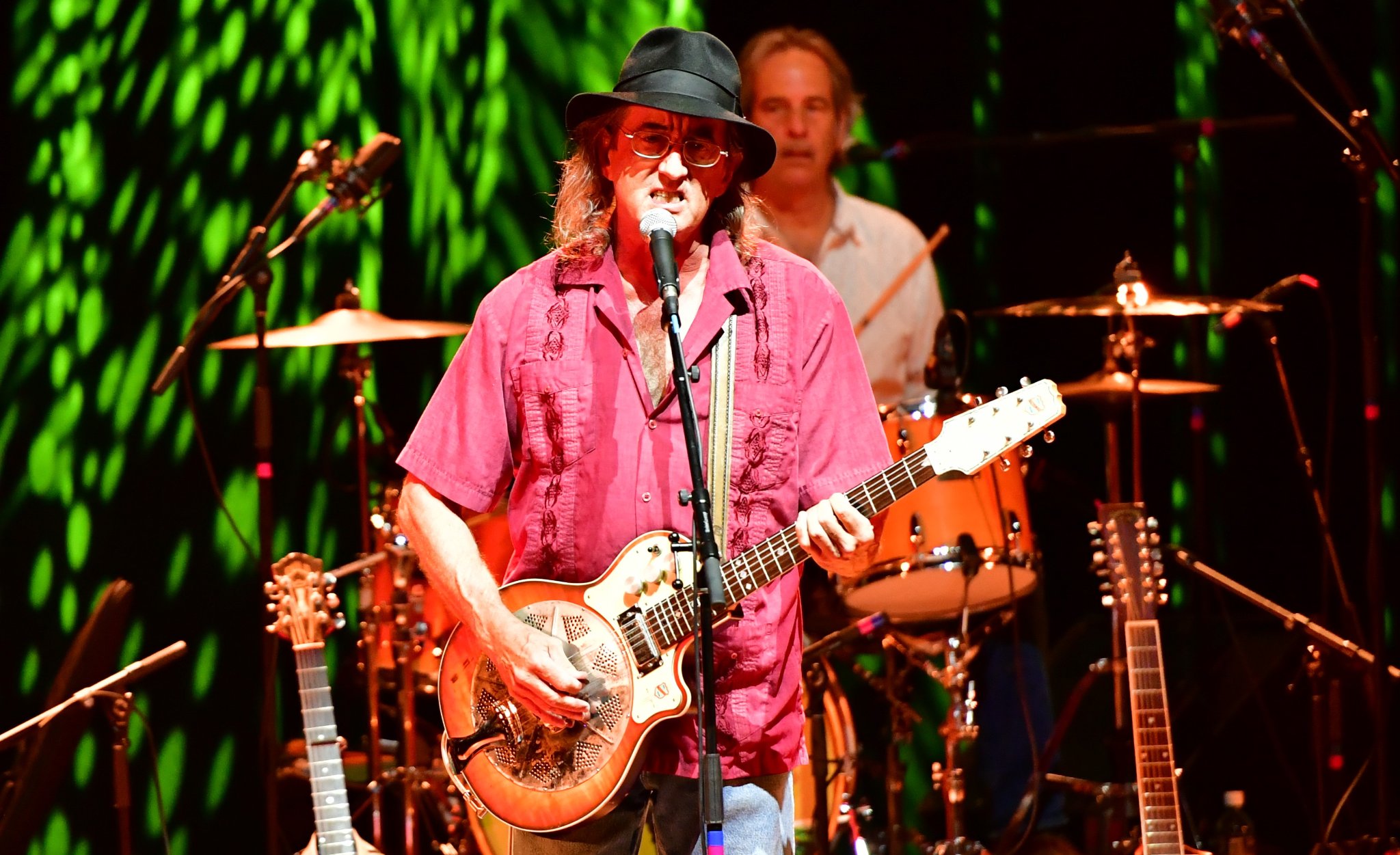

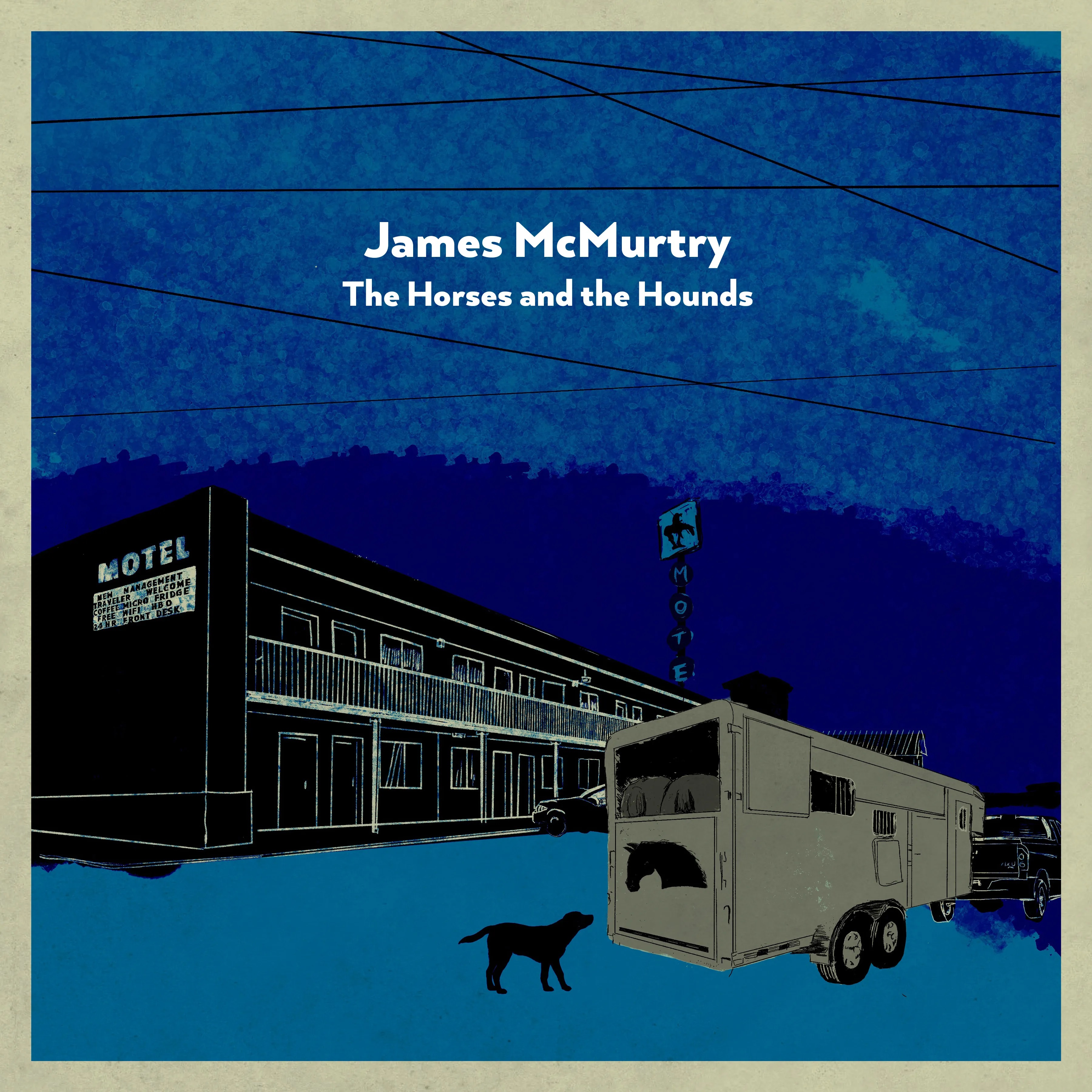

In James McMurtry’s latest album, The Horses and the Hounds, the acclaimed songwriter backs personal narratives with an elegant, yet no-bullshit approach. McMurtry recorded the album with legendary producer Ross Hogarth (Ozzy Osbourne, John Fogerty, Van Halen, Keb’ Mo’) at Jackson Browne’s Groove Masters Studio in Santa Monica, California, a world class studio that has housed such legends as Bob Dylan, David Crosby, as well as Browne himself for I’m Alive.

The Horses and the Hounds was released in August 2021 on New West Records. “I first became aware of James McMurtry’s formidable songwriting prowess while working at Bug Music Publishing in the ’90s,” says New West president John Allen. “He’s a true talent. All of us at New West are excited at the prospect of championing the next phase of James’ already successful and respected career.”

“James writes like he’s lived a lifetime,” said John Mellencamp back in 1989, when ``Too Long in the Wasteland'' hit the Billboard 200.

Stephen King once referred to James McMurtry as the “truest, fiercest songwriter of his generation.”

“James McMurtry is one of my very few favorite songwriters on Earth and these days he’s working at the top of his game,” says Americana singer Jason Isbell. “He has that rare gift of being able to make a listener laugh out loud at one line and choke up at the next. I don’t think anybody writes better lyrics.”

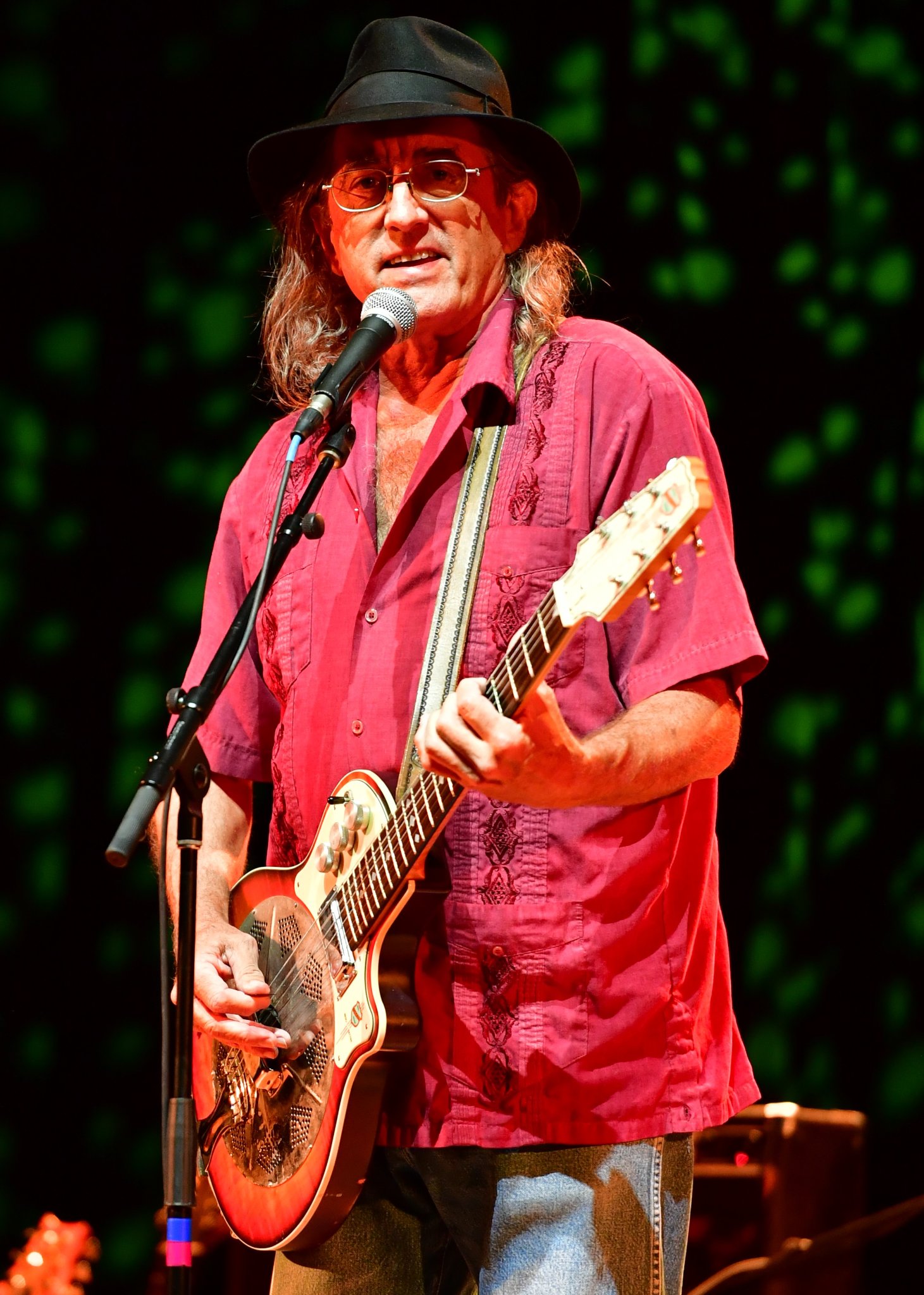

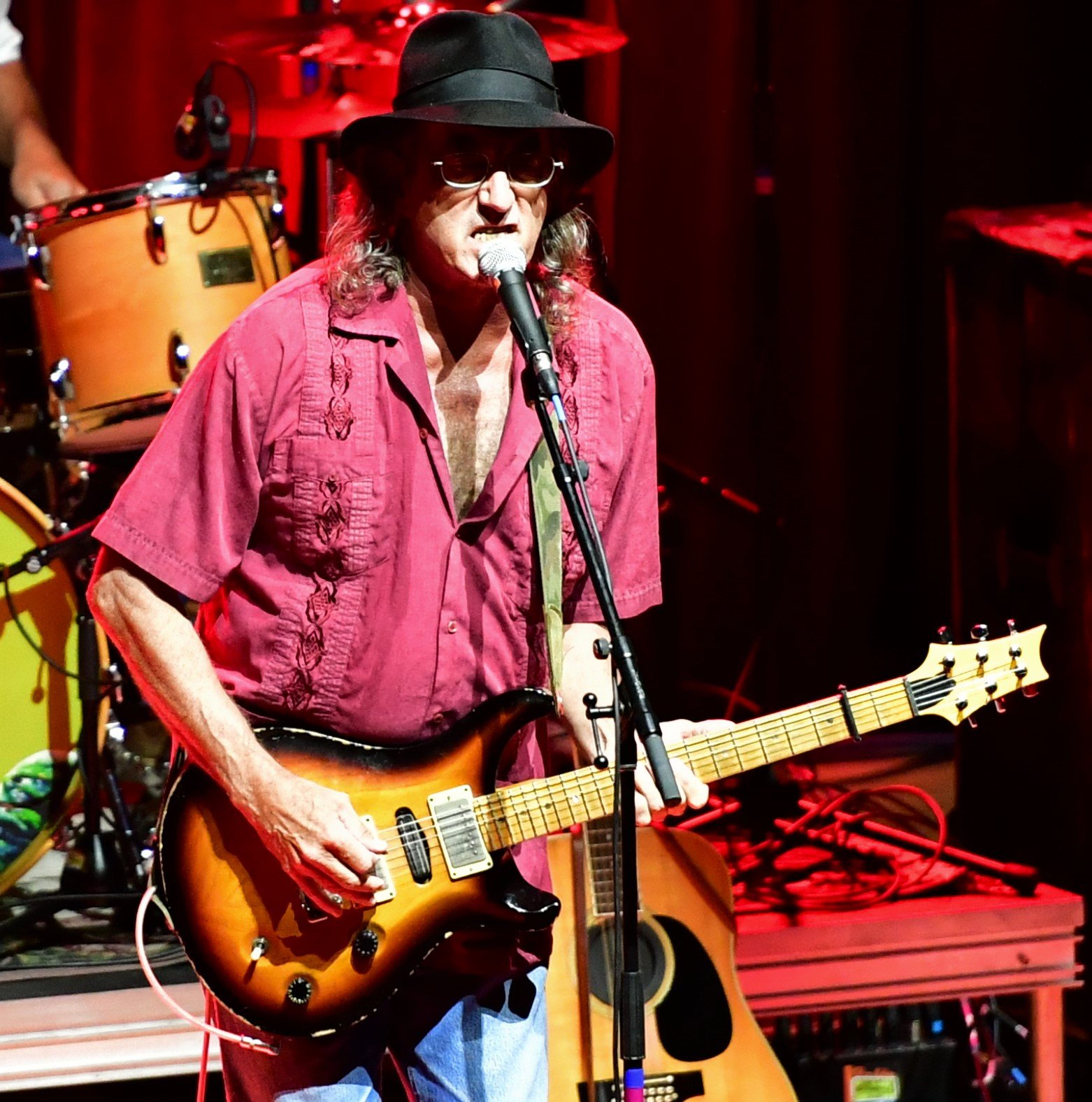

This past week, James McMurtry sat down with the Grateful Web for a candid chat. Read on below for an in-depth view into the stoic and ever-so-wise mind of the legendary songwriter.

GW: As an educator, I really appreciate that you have what I consider to be a classic educator philosophy. Teachers are often told to remain unbiased. To not have a strong opinion, or to not share it if we do. I have always felt that this fails to prepare students for critical thinking. To challenge authority in an appropriate and productive way. I really admire the fact that you speak the truth so candidly. Can you talk a little bit about that?

JM: “I don't think we teach critical thinking. It’s all about scores. I stumbled on that many years ago when I was still trying to be a student. It is one of the reasons I dropped out of college. I took a philosophy elective, and we're in there trying to study concepts, and we would come to these discussions, and nobody wanted to know about the concepts. They just wanted to know exactly what was going to be on the quiz, which was connected to their grade, or fulfilled some kind of humanities requirement, so that they could go on and be lawyers or whatever. And you know, I get that because they're coming from an economic standpoint. It was a state university, but they were giving us Descartes and Aquinas, and I didn’t understand any of it, but I wanted to at least get something out of it. So I would show up and ask questions about the concepts, and nobody else seemed to realize that if they understood the concepts then they could also pass the quiz. You don’t need to know the exact question. You can deduce that through critical thought. It's just not how these people were trained. They were trained to memorize the answers.”

GW: Obviously your father Larry McMurtry went on to become a widely respected and successful novelist and screenwriter, but weren’t both of your parents educators at one point?

JM: “My mother was more of an educator. My dad got out of it as soon as he could. It was the Vietnam era, and most of the time he was teaching creative writing to people that really didn't care about that. They were trying to stay out of Vietnam, and he didn't mind that, but they didn't want to be taught, and that was a problem for him. My mother would push through it. She'd find the ones that did want to be taught. He [Larry McMurtry] worked as an educator in order to pay the rent. His books didn't sell until Lonesome Dove, which was 1986, and he had been putting out novels for a long time. He did get some fame for the books that were made into movies, and he got a foothold in the screenwriting world with the last movie. The novels didn't sell, but he could write the first draft of a screenplay for forty thousand dollars. He'd immediately get fired because his forte was using the book as the first step towards becoming a movie. He didn't know the cinematic side, where he'd break it down shot for shot like a director, but he was really good at taking that first step. So they'd hire him, and they'd fire him. The first draft was good money.”

GW: It sounds like your father was the visionary type. I enjoy the role of writer, director and alchemist myself. As far as capturing the perfect shot, where everybody looks good and the lighting is perfect, I admire people who can do that, but that's my thing. Not yet anyway. It can be challenging to be an artist without that knowledge and skill set right now.

JM: “Well, Larry [McMurtry] just had a knack for knowing what to cut out of a novel in order to squeeze it down for a movie, while still telling a story. He was a story guy. You are talking about the perfect shot. I was a child actor in Peter Bagonov’s production of Daisy Miller. Peter was one of those cinematic guys. He wanted the perfect shot. It was the second day I worked and they had this one shot that covered eleven pages of the script, which is insane. Usually, it takes maybe a quarter page, and then you cut away. Not only that, but it was in a room full of mirrors, with foreground action in front of the camera, and background action in the mirrors, so you had to have a whole crew. It was a dolly shot, so you have a crew with dollies, booms, and lights, and actors have to hit. They're blocking perfectly, so they show up in the mirror at the right time and none of the booms or any of the equipment can show up in the mirror and get in the shot and ruin it. It took fifty-seven takes to get three prints. Back then there wasn't any digital way to send film to the lab, and if something happened to one of your prints then you’d better have a backup. We got the shot done, but it wore everybody out because it took all day. If you watch that movie, which very few people did, because it flopped— except for I believe it got an Oscar for costume design, and it really did have great costumes— but if you manage to watch that movie, and you see that shot, it's in a villa in Rome, and it goes by so fast that you don't even notice it. This one shot was a masterpiece and nobody notices. It took fifty-seven takes. I blew about sixteen of them myself, just looking into the camera.”

GW: You know, somehow that translates as a play production director. I am able to visualize it on stage, but the camera stuff? I leave that to other people.

JM: “Peter [Baganov] watched a lot of movies. He would cut school and go watch them in the fifties in New York City. There was a movie theater on every block and he'd cut school to go see whatever was coming along. So he really had a cinematic sense the same way Larry had a literary sense from reading. Larry was a voracious reader. I didn't do either of those. I listened to Kris Kristofferson and John Prine, and figured out how to write verse.”

GW: Well, I think it's impressive that you tell such excellent stories in your songs considering the fact that you aren’t a voracious reader. By the way, as somebody who analyzes poetry and who walks students through that process, I do really notice the rhyme, meter, alliteration, and all of the poetic devices that you're using, and it makes me so happy. My students and I discuss whether or not song lyrics are poetry all the time. It is hard to find a lot of depth in song lyrics these days.

JM: “Song lyrics can be poetry, in the sense that poetry can get us outside ourselves. The thing with songwriting is that you're writing for an instrument. You're writing for your voice and for your vocalization. So you want to write words you can sing. You want to avoid anything that's going to tongue tie you. Poetry doesn't have to do that. It might not ever be spoken. You can just sit with it. So the thing that has improved my songwriting the most is taking voice lessons. Not that I was trying to be Pavarotti, I just didn't want to lose my voice on the road. You learn exercises to keep your voice warmed up, and eventually it helps expand your range a little bit. Also my voice coach taught me to watch out for diphthongs and weird vowels that are going to be hard to sing so now I try to make it easy on myself.”

GW: I was going to say in regards to your voice, I grew up listening to Johnny Cash, and I was wondering if you were influenced by him at all? I also hear a little bit of Irish folk.

JM: “Yeah, you got that? Well the Irish folk probably comes through bluegrass because I grew up in Virginia, and we heard a lot of bluegrass and old time played around there. A lot of that's Gaelic oriented. I was a big Johnny Cash fan starting from around age five. Actually the first live concert I ever saw was Johnny Cash with the Carter family, Carl Perkins, and the Statler Brothers. It was a big package. I remember John Carter Cash had just been born a couple months before, and when Johnny sang “A Boy Named Sue,” he gets to the end of it, and says, ‘If I ever have a son, I think I’m going to name him, and you expect him to go, Bill or George or anything, but this time he gets to the end of it, and says, “If I ever have a son? I think I'm gonna name him John Carter. And the crowd just erupted.”

GW: Oh, My Grandpa used to sing that song all the time. Okay, this makes sense. You grew up in Virginia, and I grew up in Southern Ohio. Much of what you write about, and the stories you tell through the voices of different characters and narrators, impresses me on so many levels. For example, I grew up in the Appalachian region and was surrounded by generational poverty, and all of the things that trickle down from that. I really appreciate your ability to tell stories of similar people with similar struggles in a purely authentic and simple way. No stereotypes, gimmicks or judgments. You speak the truth and I think our country really needs that right now. There is so much division.

JM: “I've heard that the words ‘under God’ in the pledge of allegiance were inserted by the Eisenhower administration to make us feel superior to the godless communist, and it throws off the symmetry of the whole thing. It used to be that the stress was on ‘indivisible’. I took it as a warning to unreconstructed Southerners not to pull that secession because that pledge was written in 1892.”

GW: Yeah, that makes sense. Wasn't our national anthem originally a British pub song?

JM: “Yeah, the melody was a British pub song, and they took out a lot of lines. There were lines in it about, ‘No refuge could save the hireling and slave from the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave.’ And actually, we didn't have a national anthem until 1931. Think about that. You know they didn't play that, and the Union didn't play that during the Civil War, they played the battle hymn of the Republic.”

GW: And it has certainly been a slow process of nationalism and division ever since.

JM: “People get scared. They get nationalistic and racist.”

James McMurtry Tour Dates:

Wednesday, December 7, 2022 Oklahoma City, OK The Blue Door - SOLD OUT

Thursday, December 8, 2022 Fayetteville, ARK Starr Theater: Walton Arts Center - SOLD OUT

Friday, December 9, 2022 Little Rock, ARK White Water Tavern - SOLD OUT

Saturday, December 10, 2022 Little Rock, ARK White Water Tavern - SOLD OUT