When a Seattleite says ‘look on the bright side’ they’re, more times than not, actually referring to a sunny patch of pavement on the opposite sidewalk. That these words are also used to conduce vitality in the worn and haggard – who, let’s be honest, are most likely depressed due to a Vitamin D deficiency – is sheer coincidence. Or is it?

You see, Seattleites don’t just complain about the lack of sun because of the weather; it’s also because of their professions. This is a town made up of Freaks and Geeks – that is to say, tattooed rockers and their technocrat counterparts. In both cases, twenty-to-thirty-somethings spend their days locked in dark rooms staring at LCDs and tinkering with gear, and their nights drinking microbrews in dive bars. So even if the sun was beaming down on the city, who would know?

My point is: if you’re submerged in the Seattle lifestyle, you don’t think about things like lack of sunlight and fresh air until it’s too late. This is precisely why, when the planets align and a Seattleite finds themselves outside on a sunny day, things get almost pagan.

And that brings us to Bumbershoot – the three-day music and arts festival that’s been closing the summer at Seattle Center on Labor Day weekends since 1971. This year the universe seems to be rewarding us for making it through a painfully cold and gray summer with three straight days of 80-degree bliss.

Mothers, brothers, sisters, lovers all come out to play,

Soaking in a golden sun and grooving to the music sway.

I stroll into Seattle Center, Wayfarers at the ready, and start hunting down the press lounge for my credentials. Narrow sidewalks make it easy to get caught in the crowd’s flow, yet something calls to me and temptation ensues as I jump off the path, breaking free of the human locomotive and landing on shady grass. It’s not auditory bliss that draws me out of the pack, but visual sublimity. The Mural Stage (this year dubbed “The Starbucks Stage” due not only to lack of funding but also to the densely populated corporate landscape in Seattle, which is contrived of brands that will do anything to win over Shakers and Movers in this town) is breathtaking. Stationed directly underneath the Space Needle, this is the iconic Bumbershoot image.

I stroll into Seattle Center, Wayfarers at the ready, and start hunting down the press lounge for my credentials. Narrow sidewalks make it easy to get caught in the crowd’s flow, yet something calls to me and temptation ensues as I jump off the path, breaking free of the human locomotive and landing on shady grass. It’s not auditory bliss that draws me out of the pack, but visual sublimity. The Mural Stage (this year dubbed “The Starbucks Stage” due not only to lack of funding but also to the densely populated corporate landscape in Seattle, which is contrived of brands that will do anything to win over Shakers and Movers in this town) is breathtaking. Stationed directly underneath the Space Needle, this is the iconic Bumbershoot image.

An old man – complete with gray beard, tie-dye shirt, and wizard’s cane – appears next to me and wrestles out the words “Japanese Plum Tree.” It takes me a second to realize he’s referring to the short foliage that shades us, but after this initial awkwardness he opens up a bit. He says he remembers standing underneath the Space Needle while it was still being built in ’62. He remembers “smoking doobies” underneath this very tree in 1967, and remembers back when Bumbershoot was free. After a bit of the ol’ festival banter and some tales of simpler times I thank him and go on my way.

Fantasy Folklore.

I kick off the festival at KEXP 90.3’s Private Lounge, where some of the weekends top acts put on forty-minute sets for press, platinum pass holders, and any ears that happen to be tuning into FM wavelengths or streaming online from the station’s Web site. The venue looks like – and, as I later confirm, indeed is – a small stage for middle school productions. Air conditioning makes being indoors a pleasant retreat, yet my bones rattle in anticipation of an upcoming set from one of the West Coast’s premier folk outfits, Vetiver.

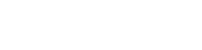

Based in San Francisco, Vetiver is led by singer-songwriter Andy Cabic. Cabic has become somewhat of a household name in the Northwest – that is, if you happen to live at a commune or art school. He’s worked with Eric Johnson, has released material on Sub Pop, and channels Jerry Garcia with his calm vocal delivery and jingle-jangle finger picking.

Based in San Francisco, Vetiver is led by singer-songwriter Andy Cabic. Cabic has become somewhat of a household name in the Northwest – that is, if you happen to live at a commune or art school. He’s worked with Eric Johnson, has released material on Sub Pop, and channels Jerry Garcia with his calm vocal delivery and jingle-jangle finger picking.

Vetiver takes stage and I’m immediately drawn to lead guitarist Daniel Hindman, who comes out with a newly polished cherry sunburst 12-string Rickenbacker. Cabic murmurs some form of thank you into his microphone and cues the band. They start with “Rolling Sea,” the opening number off their first Sub Pop release, 2009’s Tight Knit. Although – in typical Seattle fashion – we’re currently indoors, this tune is riddled with the serenity felt when you have “only the sky above you for a roof.” Hindman artfully uses his volume pedal to capture that classic Pedal Steel timbre, and a light tremolo effect adds an irresistible cadence to the already twangy 12-string.

The song ends on a beautifully transient vamp, wherein Cabic repeats the lyrical hook, “oh it’s been such a long time.” It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what’s so compelling about Cabic’s unrushed, warm vocal tones, yet witnessing Vetiver live for the first time does bring new insights to this longtime fan. Cabic is like a scarecrow; it’s as if he’s stood motionless for 1000 years, observing a world of good and evil swinging on its pendulum ad infinitum. In my fantasy folklore, the scarecrow called Andy – after a millennium of solitude – is given the breadth of life and an acoustic guitar. The rest, as they say, is history.

Here comes the Sun King.

After grooving along to a stellar set featuring cuts from To Find Me Gone, Tight Knit, and Vetiver’s latest LP The Errant Charm, I escape the Siren’s Song that is central air-conditioning and march onwards toward a baking sun. The festival is more crowded than forty minutes prior, the sun more central in its blue expanse. Wayfarers out and on.

As I wander toward the Fountain – a behemoth sprout near the needle that, on most weekends, serves merely as a photo op for tourists – I realize that this is where the crowd’s headed. The Fountain launches thick streams of cold water like a cacophony of cannonballs; their sprays unpredictable and arches mesmerizing. Every species of Bumbershooter is represented in true waterhole fashion: toddlers playing tag, teens sparking cones, age-old hippies cooling their feet, and young parents trying to make sense of it all. From where I stood, the scene looked nothing short of a pagan ritual honoring the Sun King.

As I wander toward the Fountain – a behemoth sprout near the needle that, on most weekends, serves merely as a photo op for tourists – I realize that this is where the crowd’s headed. The Fountain launches thick streams of cold water like a cacophony of cannonballs; their sprays unpredictable and arches mesmerizing. Every species of Bumbershooter is represented in true waterhole fashion: toddlers playing tag, teens sparking cones, age-old hippies cooling their feet, and young parents trying to make sense of it all. From where I stood, the scene looked nothing short of a pagan ritual honoring the Sun King.

I start walking around the Fountain and hear the one two, one two of a nearby sound check. It’s coming from a small tent with a banner that reads: TOYOTA FREE YR RADIO. I discover that bands will be playing twenty-minute stripped down sets here all weekend. Up next: Pickwick.

Break On Through.

Pickwick is the group everyone’s talking about at Bumbershoot. Like The Head and The Heart last year, this Seattle-based band has capitalized on the Northwest’s plentiful summertime festivals and it’s paid off. They say word-of-mouth translates into fans, and Pickwick was on the tip of the collective tongue all weekend.

As the story goes, Pickwick began when front man Galen Disston left his hometown of LA and moved to Seattle a few years back. His plan was to start an alt-country band, and Seattle seemed like the place to do it. However after playing the circuit for a while, Disston became frustrated with being one among a thousand other alt-country bands in this town.

That’s when he happened upon Sam Cooke’s A Change Is Gonna Come. Disston fell in love with the freedom and melodic ease of Cooke’s voice, and decided to change the direction of his band entirely.

Pickwick walks onto the small tent-stage with six of their seven members. They’re instrumentally unassuming with just an acoustic guitar, electric piano, bass drum, and shaker. Disston has wild hair, designer glasses, a miniature tambourine, and a guilty smirk.

Everything but the smirk remains as they start their first tune, a soulful a cappella. The Disston of a few moments ago – the one who looked like that goofy friend of yours from high school – is gone. In his place is a man with chops comparable to the greatest vocalists, a man reaching into the depths of his own soul and returning with a taste of the infinite. Even his movements, which at first seemed awkward and restrained, now contribute to the overpowering nature of his voice.

Everything but the smirk remains as they start their first tune, a soulful a cappella. The Disston of a few moments ago – the one who looked like that goofy friend of yours from high school – is gone. In his place is a man with chops comparable to the greatest vocalists, a man reaching into the depths of his own soul and returning with a taste of the infinite. Even his movements, which at first seemed awkward and restrained, now contribute to the overpowering nature of his voice.

Pickwick played five songs, which are spread out over their three 45 vinyl releases. The most memorable tune – and the one everybody seemed to know already – is a funk number called “Hacienda Motel.”

My jaw still dropped from Disston’s vocal prowess, I decide to catch them again, this time plugged-in at the Experience Music Project Stage. The venue holds 450, and by the time I get there hundreds of people are being turned away. Luckily, my press pass works its magic and I get to see Pickwick play another mind-blowing set.

Round and round, up and down.

To end the day, I catch Vetiver playing their main set at the beautiful Fountain Lawn Stage. Not surprisingly, Cabic’s songs sound even better when outside – I watch the sun disappear behind an orange horizon as Vetiver plays the sexy “Another Reason To Go,” a rocking rendition of “You May Be Blue,” and The Errant Charm’s dream-pop jingle “Wonder Why.”

Whereas Vetiver’s early work captures the soil, dirt, and trees, their new stuff is of the sky, azure, and breeze. Hindman’s 12-string gives the feeling of being pleasantly lost in a cloud, and my dream pop trance is complete as he goes into the opening riff of The Go-Betweens’ 1988 hit “Streets of Your Town.”

I spend the late afternoon sitting by The Fountain, listening to the clashing echoes of performances from nearby stages. The auditory cocktail of flowing water, laughing children, and distant guitars brings me to an ephemeral, somewhat spiritual place. I luckily snap out of this trance just in time to catch

I spend the late afternoon sitting by The Fountain, listening to the clashing echoes of performances from nearby stages. The auditory cocktail of flowing water, laughing children, and distant guitars brings me to an ephemeral, somewhat spiritual place. I luckily snap out of this trance just in time to catch