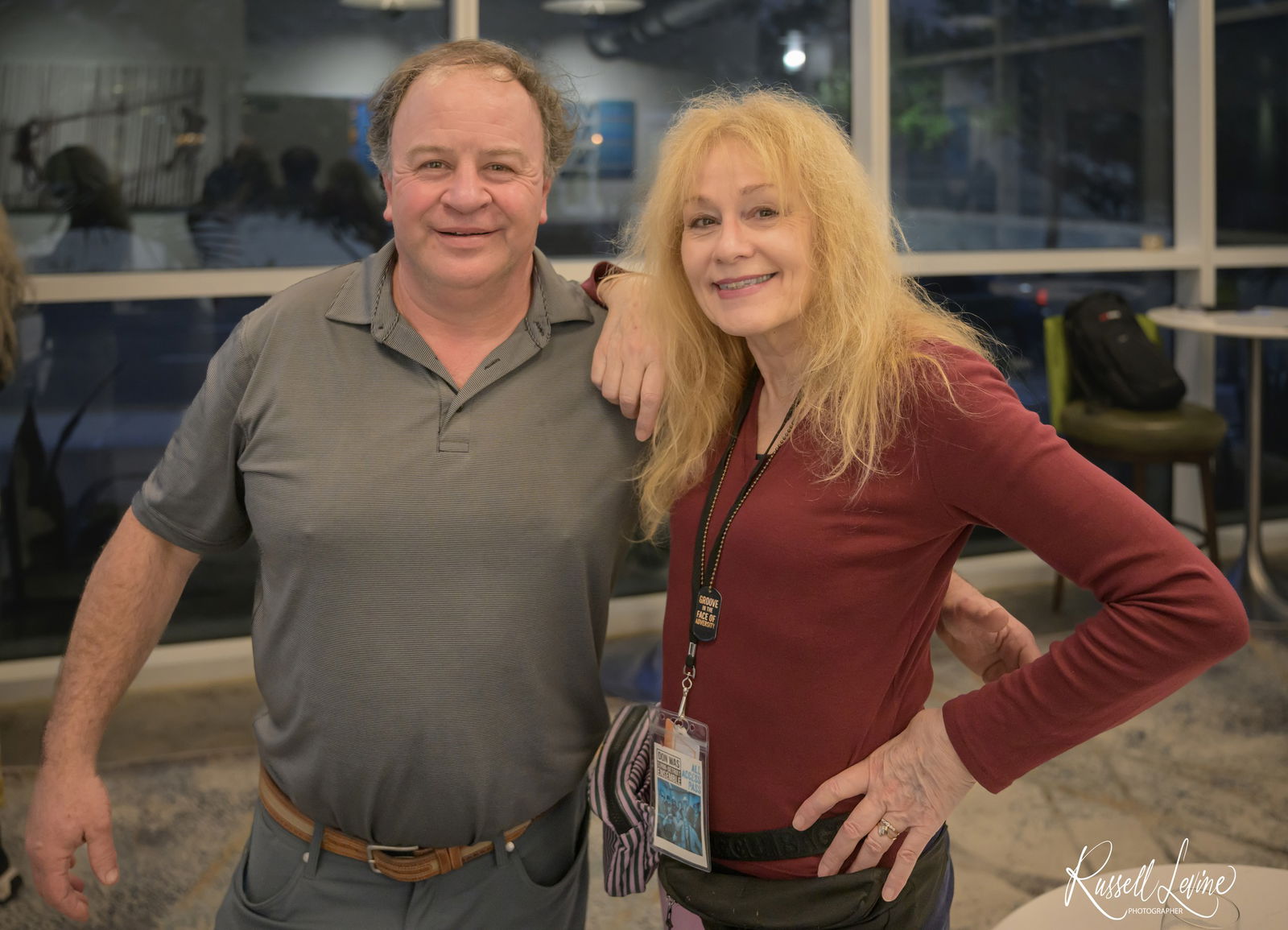

Article Contributed by Russell Levine

Published on 2026-02-17

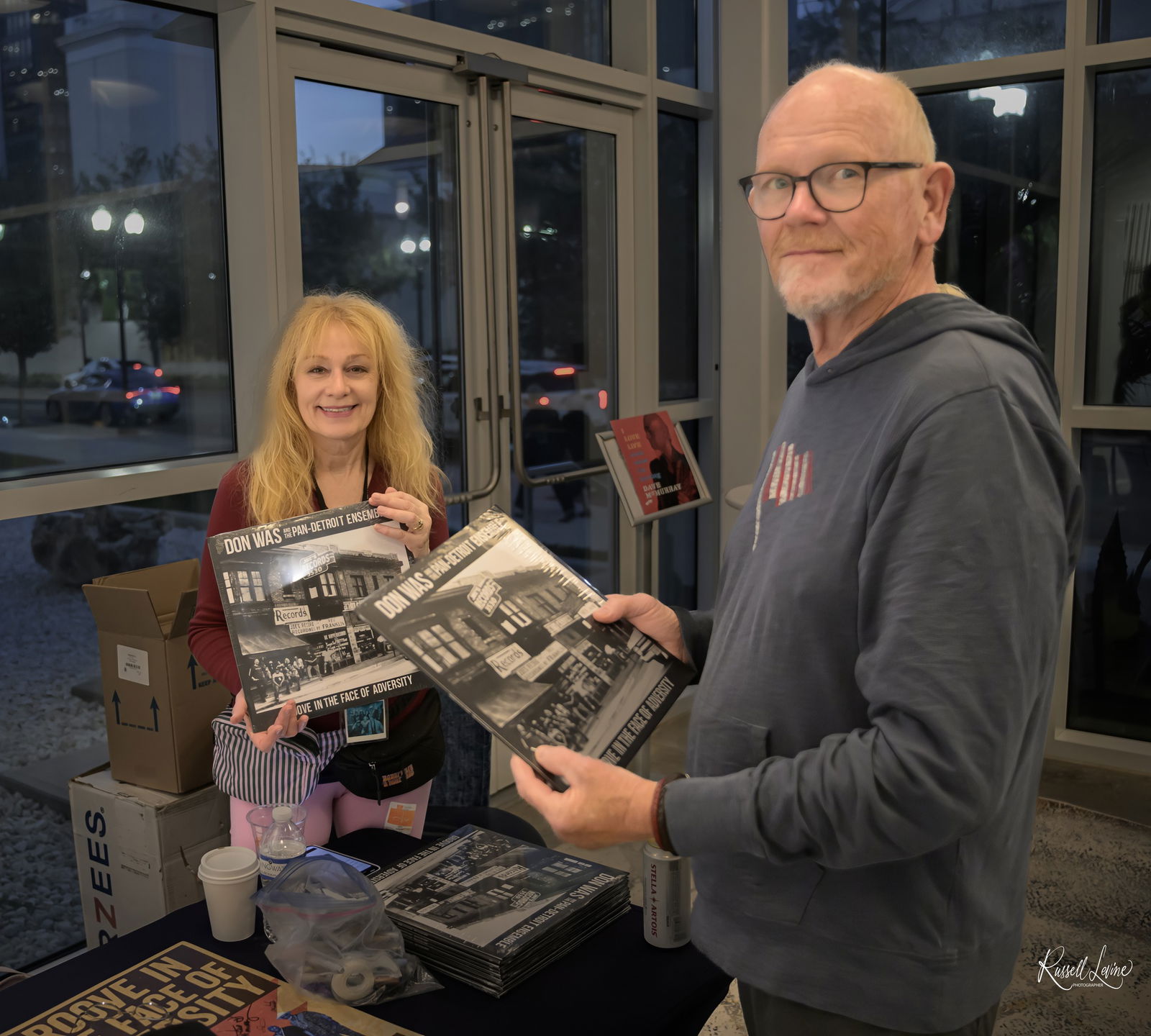

Don Was & The Pan-Detroit Ensemble | Orlando, Florida | February 13th, 2026 | photos by Russell Levine

“This wasn’t Grateful Dead karaoke — it was Detroit alchemy in a 150-seat jazz sanctuary, where every note breathed and every groove carried history.”

There are rooms built for spectacle.

And then there are rooms built for truth.

Judson’s Live is the latter — a 150-seat jazz bunker wrapped in warm wood, soft stage light, and acoustics so honest they border on confrontational. You don’t hide in this room. You either mean it, or you don’t play.

On February 13th, Don Was & The Pan-Detroit Ensemble meant it.

Before a single note, Don Was addressed the elephant in the room: grief. Just before this tour, he lost a close friend and bandmate Bob Weir. He didn’t feel like stepping on stage.

And then he remembered a story Weir once told him about August 9, 1995 — the day Jerry Garcia died. That very night, Weir was scheduled to perform in Hampton, New Hampshire with RatDog. He could have canceled. He chose not to. Music was the only way to process loss.

For Was, that memory became a compass. The stage was no longer a burden; it became a form of healing — for the band, the audience, and the spirit of music itself.

Was has spoken openly about joining Bob Weir’s Wolf Bros and feeling intimidated by the legacy of Phil Lesh. He initially tried to emulate Lesh’s virtuosic melodic style and found himself in what he called a “stylistic limbo,” worried that without imitation, it would sound like a bar band covering Dead songs.

Weir’s direction was simple: be yourself. Don’s own voice, he realized, was the truest way to honor the music. The ensemble carries that philosophy tonight — reinterpreting the Dead through Detroit soul, jazz intuition, and lived experience.

The first set was leaner, tighter, like a jazz band that knows exactly where it wants to land.

They opened with “The Music Never Stopped,” immediately establishing a Detroit pulse — bass and drums locked in a measured sway, horns accenting without bombast. “I Ain’t Got Nothin’ But Time” stripped away Hank Williams’ twang and rebuilt it with a soulful Motor City pocket.

“You Asked, I Came” arrived with confidence, establishing the ensemble’s interplay: sax, trumpet, and trombone trading lines like conversation, keyboard and guitar threading nuance underneath.

Then came “Elvis’ Rolls Royce” — a surreal, soulful track Don recorded decades ago with David Was. Legend has it David stumbled upon an auction for Elvis Presley’s 1963 Phantom V while walking around London. Tempted to “steal it back to Graceland,” he wisely wrote a song instead. Leonard Cohen had recorded the original spoken-word part, but tonight, Was took the mic. The lyrics — absurd, cinematic, and steeped in late-night R&B groove — took the room on a transatlantic joyride without leaving Orlando.

“Help > Slipknot! > Franklin’s Tower” unfolded like a slow-motion chain reaction — each note deliberate, each solo a punctuation mark, each horn line a minor miracle. “Crazy Fingers” hovered, elastic, psychedelic in small doses, and “I Can’t Wait Till I Get Home” grounded the set back in Detroit soul.

The set closed with “Shakedown Street” and “This Is My Country,” the former ending after Luis Resto’s dissolving keyboard solo, the latter carrying a quiet, pointed weight. By the end, the band and room were fully aligned — the music no longer being performed at the audience, but with them.

Don Was, bass and musical director, doesn’t fill space. He defines it. He guides without forcing, like a man who has produced half of modern music and knows the difference between volume and authority.

Saxophonist Dave McMurray moves between jazz phrasing and soul exhale effortlessly. His lines cut with precision, hover with warmth, and interact with the ensemble like conversation in mid-air.

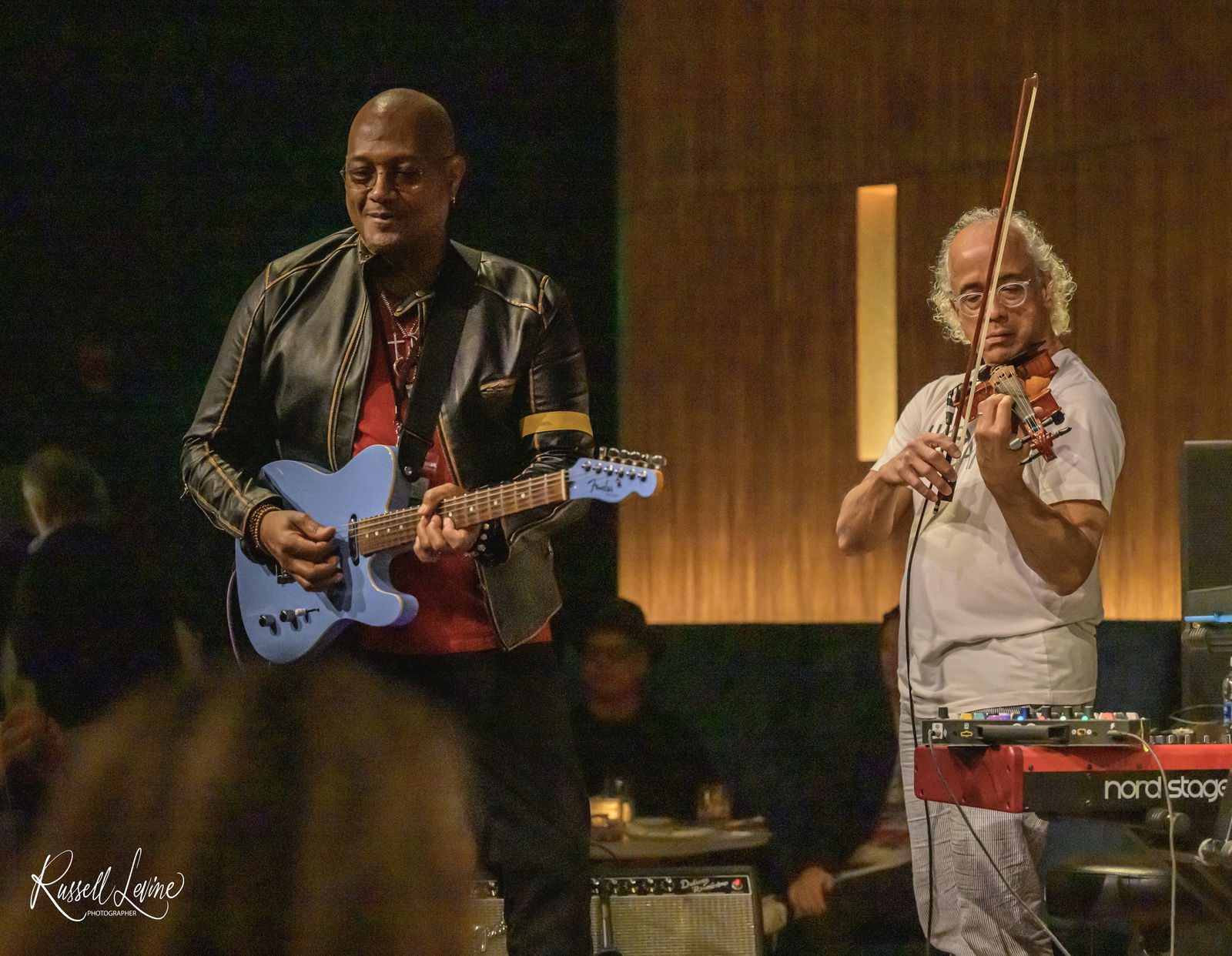

And then there’s Luis Resto — Academy Award– and GRAMMY Award–winning producer, known for his work with Eminem. During the “Blues for Allah” set, Resto stepped from the keys to a violin, referencing the album’s mystical cover. The violin didn’t decorate; it became elemental, bending Eastern modality into Detroit soul, hovering over the arrangement like a spirit.

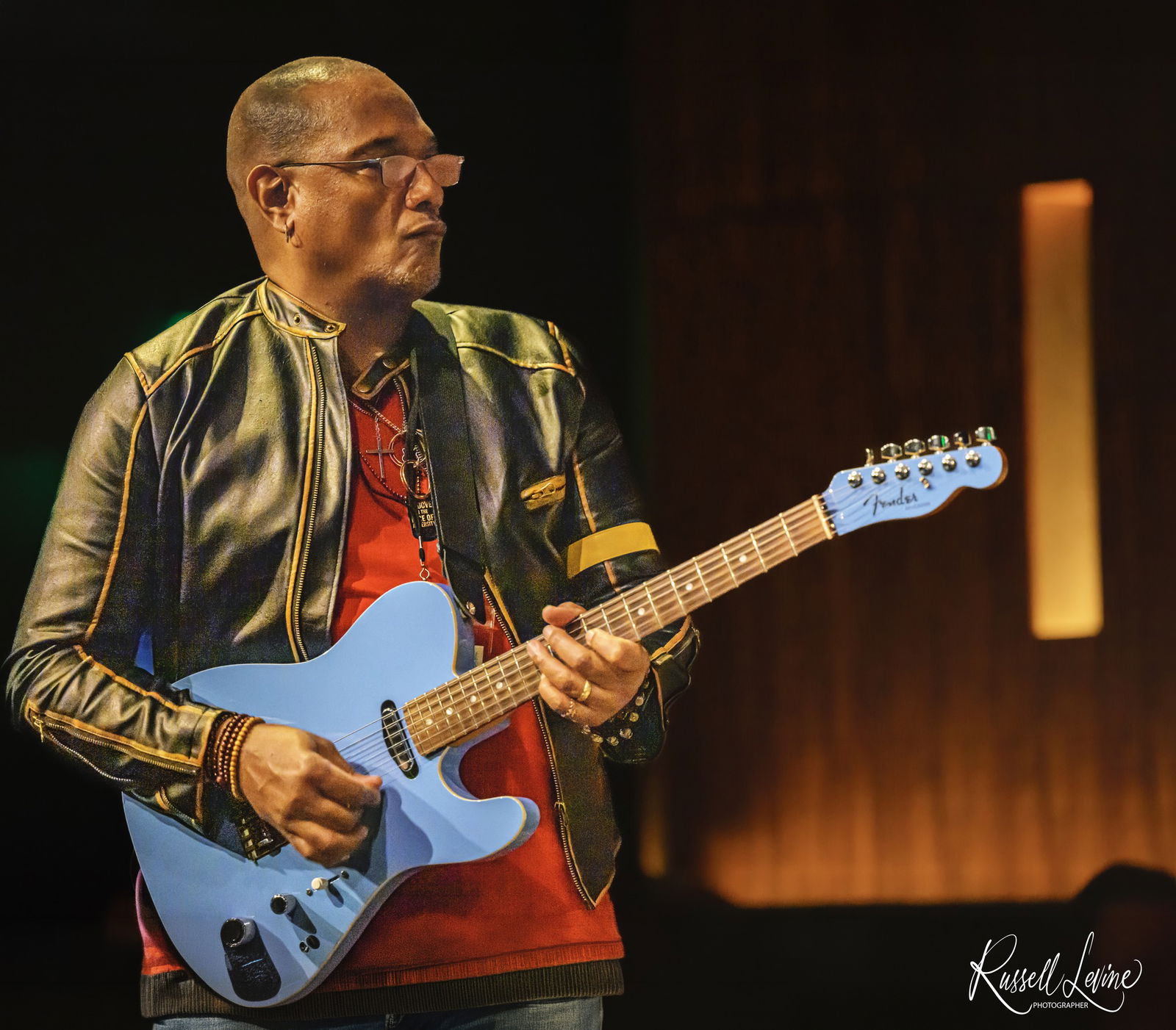

Trumpeter John Douglas and trombonist Vincent Chandler supply both fire and nuance. Drummer Jeff Canaday and percussionist Mahindi Masai form the rhythm spine, deep and elastic. Guitarist Wayne Gerard threads blues grit and funk syncopation throughout. And Steffanie Christi’an’s vocals anchor the ensemble — soulful, exacting, magnetic.

These are not just players. They are Detroit architects of texture, listening to each other, and to the room.

The second set dove headfirst into exploration.

“Hello Operator” kicked things off with a propulsive, horn-lined groove. “Nubian” and “Morocco” followed, bringing the ensemble’s jazz-funk chemistry into sharp relief. “Loser” — Jerry Garcia’s solo composition — was reframed, Detroit-ified, with horns accentuating its lilt and Christi’an’s vocals coloring its melancholy.

Returning to “The Music Never Stopped,” the band layered subtle improvisations over the familiar theme. “King Solomon’s Marbles” highlighted McMurray’s urgent sax lines, Chandler’s trombone soaring, and the keyboard weaving textures underneath.

Then came the centerpiece: Blues for Allah, performed in its entirety. From “Help on the Way” through the sprawling title track, the ensemble didn’t mimic. They interpreted — with groove, soul, and jazz intuition. Resto’s violin floated through the mystical passages, horn lines danced with subtle psychedelia, and the percussion provided global inflection that felt at once timeless and immediately Detroit.

“Marauders” and “Insane (Wheel Me Out)” extended the ensemble’s rhythmic conversations, teasing, expanding, and snapping back. “Shakedown Street” returned for a long, celebratory ending, and the show concluded with the pointed defiance of “This Is My Country.”

In an era when nostalgia can too easily become replication, Don Was & The Pan-Detroit Ensemble chose reverence without imitation. Inside the warm wooden embrace of Judson’s Live, these songs weren’t revived — they were reinterpreted through Detroit soul, jazz instinct, and lived experience. The music wasn’t nostalgic. It was alive, tactile, intentional.