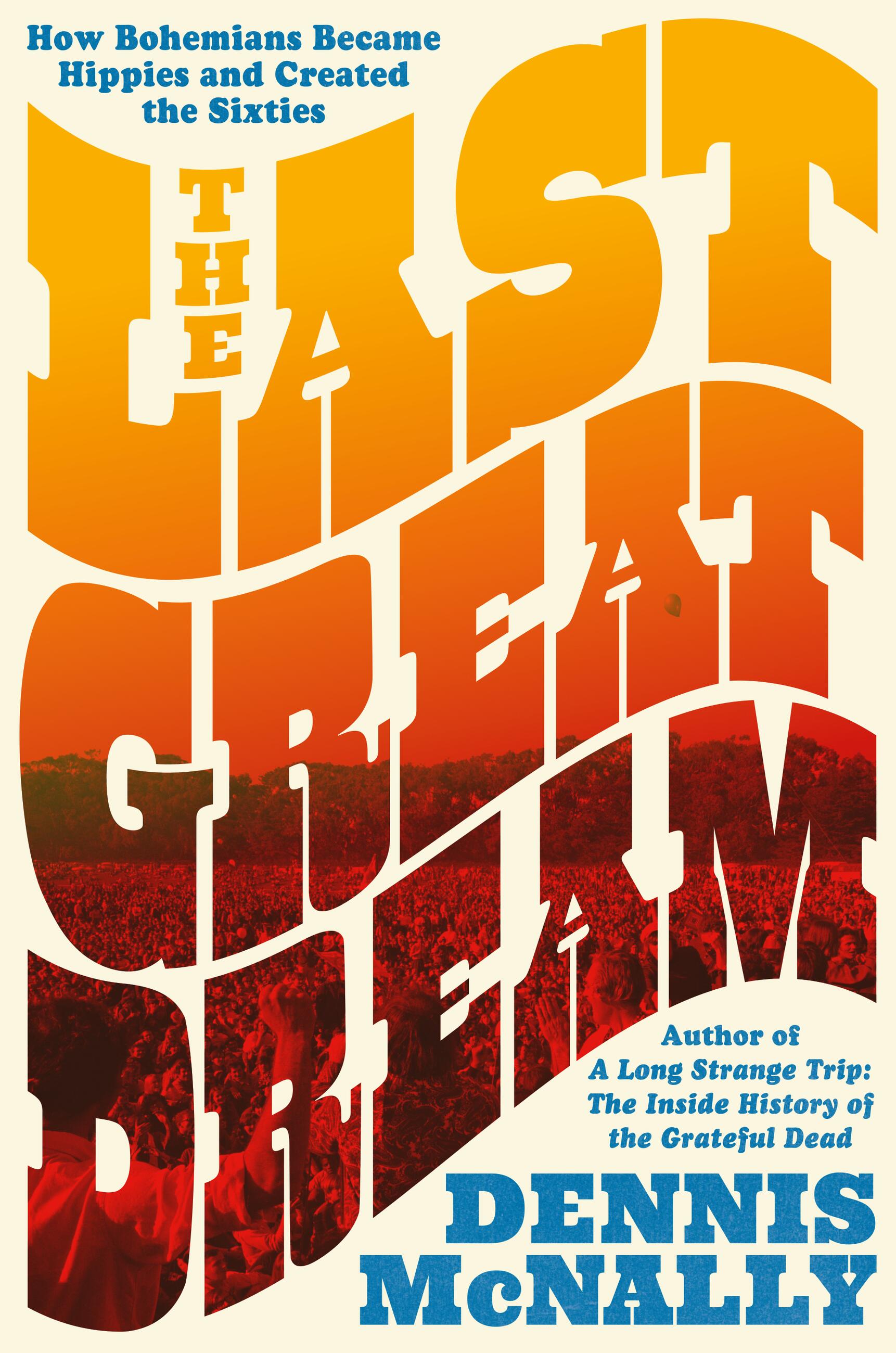

This is the second of two articles about Dennis McNally’s new book The Last Great Dream: How Bohemians Became Hippies and Created the Sixties. The first article, a review of the book, can be found at https://www.gratefulweb.com/articles/last-great-dream-dennis-mcnally-review.

The Last Great Dream (Grand Central Publishing, 2025) might be Dennis McNally’s last great book – if only because it might be the last one he writes. In one sense, it would be a fitting fare-thee-well for McNally’s career as an author. The Last Great Dream is a culmination of sorts, a final summation of a life spent dissecting and digesting the antecedents and outcomes of the 1960s countercultural explosion in America. (Or he might surprise everyone, including himself, and write another book. Watch this space!)

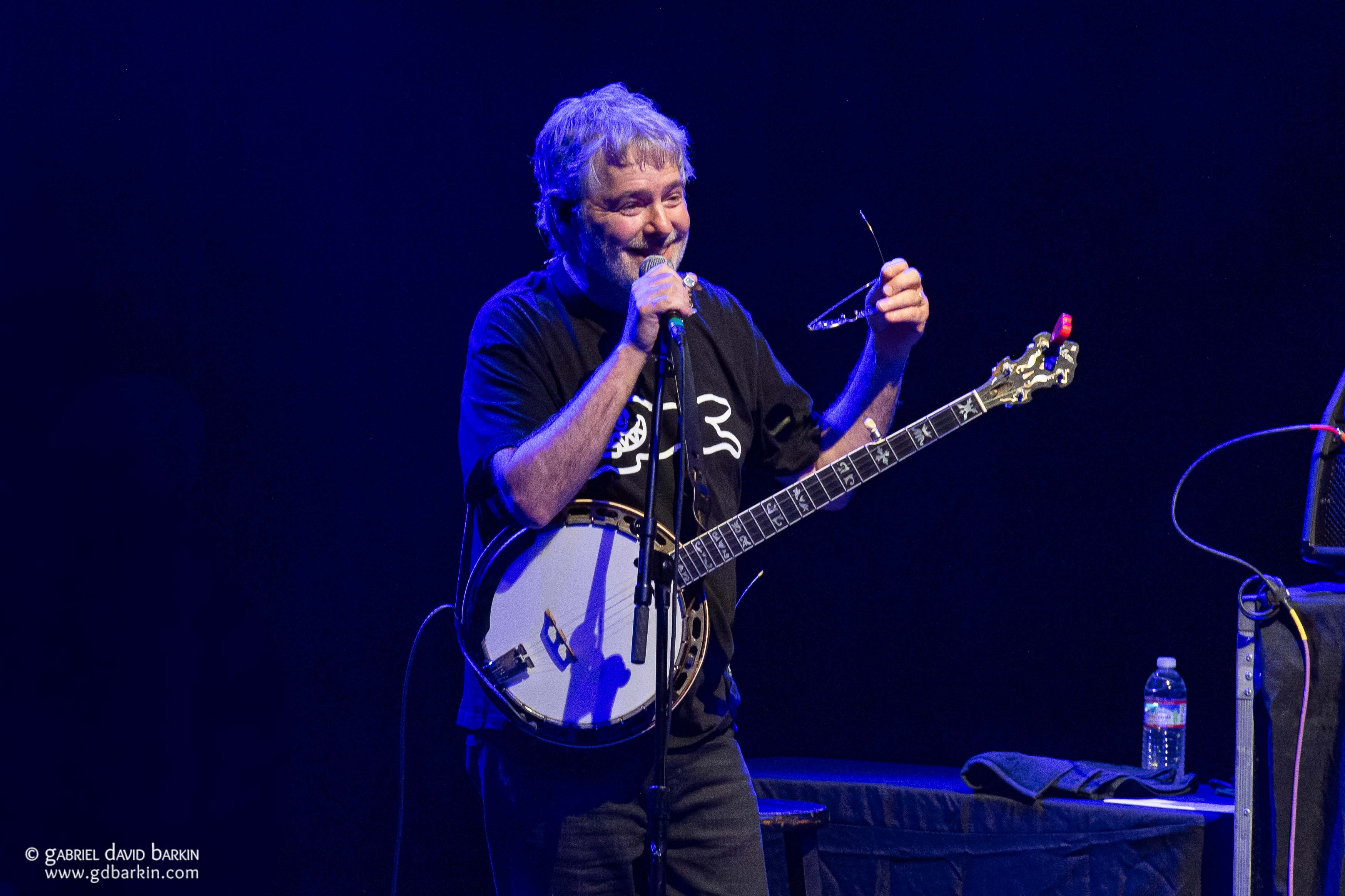

McNally may be best known to Grateful Web readers as the Grateful Dead publicist from the mid-1980s until several years after Jerry Garcia died. While he’s technically a member of the “Baby Boomer” generation that was at the core of the counterculture eruption, McNally himself was not a ’60s hippie. He did not “get on the bus” until a friend took him to his first Grateful Dead show in the early ’70s. So The Last Great Dream is not a firsthand account.

And perhaps that’s what makes this book work so well. McNally is a meticulous researcher. The Last Great Dream is a historical account of the evolution of post-WWII arcane Bohemian artistic and philosophic expression. As an author, McNally mostly tells the story by letting the perpetrators, participants, and witnesses speak. Hundreds of sources, quotes, and citations relate how an esoteric movement morphed – some might say rose, others might say fell – into mainstream pop culture. The result is a multitude of tidbits and tales woven into a narrative that is instructive as much as entertaining.

McNally and I met for a brief conversation a few weeks ago to discuss The Last Great Dream. Shortly after we met, I read a new book by Brian Eno and Bette Adriaanse that summed up my own takeaway about the countercultural roots and outcomes recounted in The Last Great Dream:

“Feelings, especially socially shared ones, guide us towards a sense of what we think is right, but they also guide us away from things. People pay a lot of attention to what other people are thinking, and they start to feel the friction of being not fully in agreement with others. This can arouse feelings of anxiety or triumph . . . but it doesn’t pass unnoticed.” – From What Art Does (Faber & Faber, 2025)

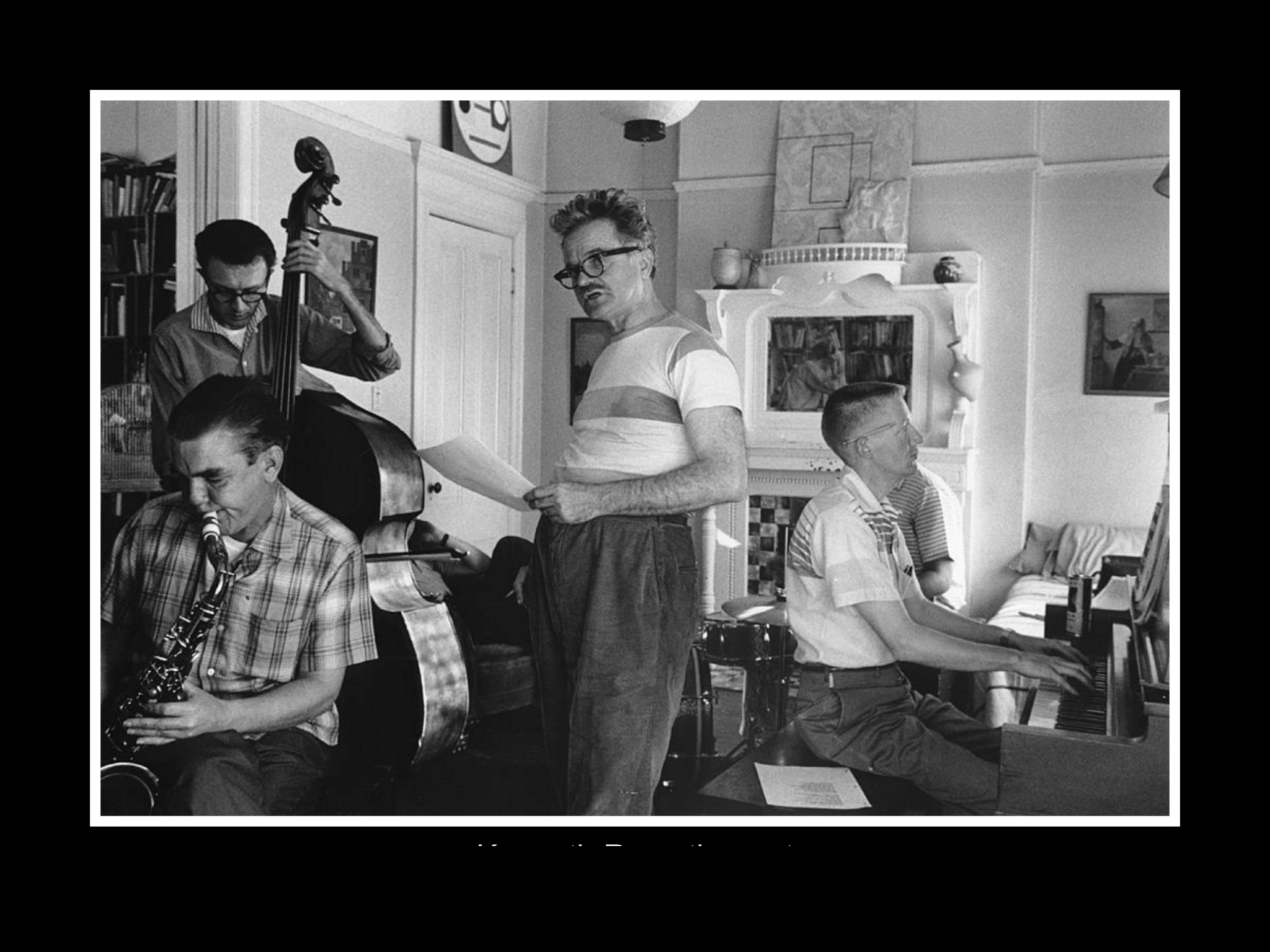

The following interview has been edited for clarity. Accompanying photos are all from The Last Great Dream, courtesy of Dennis McNally.

Gabriel David Barkin (GDB): I read the book, finished it yesterday, and really enjoyed reading it. Tell me why you wrote this book, your fourth book related to what we can broadly call “the counterculture” in America. Why this book, and why now?

Dennis McNally (DM): Why now is because I finished it. [Laughs] As with all of these things, I fell into it.

GDB: That’s sort of how you describe your entire career, isn’t it?

DM: In 1972, I was thinking about a dissertation topic, and I sort of mumbled about the Beats. My friend said, Why don't you do Kerouac? His papers are at Columbia, and you can stay with my friends in the Bronx.

Now, when you're a graduate student – I was at UMass Amherst – and you have no money, and somebody tells you, I got a free bed for you in New York City; that's a big deal. And coincidentally, my parents had, around that time, moved ten miles from where Kerouac was from. So the universe was whispering in my ear, Yeah, this is a project you can do.

My friend was also a Deadhead. I got the disease from him. And the obvious connections of Neal Cassady as Dean Moriarty in On the Road, and then of “Cowboy Neal at the wheel.” I went, Oh, that's my next book, Grateful Dead. I had no clue as to how to approach the band, but I assumed that if I knocked on their door (which I didn't know where it was) and said, You know, hi guys, I want to write a book about you, they would have said, Take a number.

So, long story short, I met Jerry and mentioned the Kerouac book and discovered that On the Road was, like, his Bible. And he liked my version of Kerouac's life. So, eventually, he said, Why don't you do us? To which I said, Good idea.

But then, eventually, I went to work for them. And you can't write an honest history and be the publicist on the same day. So I put it on the shelf. I kept a notebook for, you know, the good lines, the funny ones. And then, finally, in 2002, I put out A Long Strange Trip [Crown Books, 2003].

And then I did a book on the further background of what bumps young white kids out of conventional American culture and into some kind of alternative – which, generally speaking, ends up being what we call Bohemia. Which is to say, in America, we talk about freedom all the time as the great American value. But there's two obvious kinds of freedom. There's one that says you're free to make the most money you possibly can, which is the conventional idea of American freedom – you know, our current president, for instance.

And the other, in contrast, is the idea of complete freedom of thought. My favorite person on the planet is Thoreau. He's not a Bohemian in that, first, as far as anybody knows, he was a virgin to the day he died; and second, he never drank. However, nobody was better at thinking unconventionally.

You take it from there, and it flowers, most emphatically, in the ’60s.

I was interviewing Michael McClure, the poet, and I said, Why did On the Road have such an amazing impact? And he sort of looked at me – you know, big stop in the conversation – and he says, Dennis, did you live in the ’50s?! Well, technically yes, I was ten when it ended. But the point he was making was about the level of oppression, of repression, of self-suppression. That was an era in which [the television show] Father Knows Best was kind of accepted as reality, and the values were so limited. On the Road caused this explosion amongst youth because it was the first time anybody had offered them an alternative in ages.

GDB: That perspective is often missed by younger generations. My mother gave me a copy of On the Road when I was in college in the ’80s, and I loved it. But I didn't have that perspective that McClure was talking about – that when it was brand new, like when rock and roll was brand new, it was revolutionary. It was insurgent. There were also elements of that when punk rock was brand new, when rap was brand new. But maybe nothing like what was going on in the ’50s and ’60s, the eras you write about in your new book. And we’ll talk about why that was in a moment.

But first, before you wrote about Kerouac in grad school and then got into the Grateful Dead scene, did you actually experience any of this stuff that we're talking about – that stuff we broadly call counterculturalism or Bohemian? Was that part of your life in the ’60s?

DM: I graduated high school in ’67. That winter, I was sitting in the public library looking at Life magazine, and there was a picture of Jerry [Garcia] – the picture of Jerry in his Uncle Sam hat at the Human Be-In. And I sort of went, Oh, that's interesting. I mean, it was interesting enough to register on my mind, even though I hadn't heard the music yet. The album came out in March, and I didn't hear it till that fall in college.

So the answer – my theory for why I have devoted so much time in my adult life, half of my adult life, to writing these books – is that I missed it all.

I was just a college kid, and then a graduate student. It wasn't the same. I've been trying to catch up ever since.

GDB: Sure, I think a lot of us Deadheads have been doing the same thing. I saw my first Dead show in 1980, but so much of what captivated me didn't hit until about my fifth show in Ventura when I camped out on the beach with thousands of Deadheads. All of a sudden, I kind of got the gist of the culture, and it resonated with me in part because of my romanticized notions, as a late-to-the-party hippie, of the ’60s scene that I’d read so much about – the good stuff, anyway. A scene for which I was too young. But then I found that part of that “thing” was still alive on Dead tour.

So let’s talk about your exploration of the ’40s and ’50s in The Last Great Dream. Radio was booming nationwide, and then television came along. There was mass consumption and consumerism sold not just by advertising, but also because almost everybody in the country, for the first time in history, was experiencing a shared version of “reality.”

How does that feed into the narrative in your new book, from the post-war era through, let's say, the Monterey Pop Festival? Why was that period so ripe for laying the groundwork that led to a massive cultural revolution?

DM: There's a wonderful image – the cover of The Saturday Evening Post. A 1950s young couple, engaged to be married (white, of course), are sitting under a tree on a summer night daydreaming. And what are they daydreaming about? A freezer, a dishwasher – appliances that had not existed before the ’50s. There was an incredible boost in prosperity in the ’50s, so you were able to afford all these things. By the end of the decade, almost everyone had a television.

Television existed to sell advertising and encourage consumerism. It would reach the point of worshiping consumerism. This was the great privilege of being an American: you got all this stuff. And the only catch was, you kept your mouth shut. There was no divergence of opinion at that time.

People didn't really know much about communism at all – you know, “Kill commies!” And this connects to the present day like crazy. “Commies” were anti-Christian. You did not get into that stuff if you were smart; you avoided talking about that sort of thing.

We've now got outright Christian nationalists who think that the separation of church and state in the Constitution – oh, that's not what they really meant. Really? Can you read? How about “Congress shall not…”?

Back in that post-war period, there was this incredible upsurge after a horrendous depression and then a war that had consumed everyone's life for five, six years. You finally got this “happy time” and this peace, and there's prosperity. By contrast to what came before, it was extreme. And you had all these goodies, and you had credit cards that allowed you to get them and not have to save up for them. There's a definite shift in values from being thrifty to get what you want; you deserve it, even if you can't afford it.

GDB: So conformity was king, and consumption was the way to show allegiance. But not everybody played the game.

Reading in The Last Great Dream about the ’40s and ’50s in particular, a lot of the countercultural people you interviewed and wrote about were lesbian, gay, bisexual. Many of these people moved to San Francisco, New York, and Los Angeles; they weren't from there, they came there from somewhere else. Do you think they were driven to come to a place where they were going to be part of something new (the Bohemian counterculture) and wanted to express themselves artistically? Was that part of the plan, so to speak – to proactively upset the apple cart of conformity and consumerism and create something new? Or was it that they just needed to leave where they were?

In other words, did the people make the place, or did the place make the people? How do you see that dynamic?

DM: Well, the place welcomed the people. It's very hard to be diversionary, sexually or whatever, in rural America – everybody knows your business. It's difficult. But there's an inherent amount of sophistication in a city, particularly, say, in New York and San Francisco: everybody doesn't know your business, and there's a certain amount of freedom to explore who you are.

San Francisco was the model for this. Remember, San Francisco was not created as a business enterprise, which is what most cities are about ultimately. It was created by a bunch of whacked-out losers – people who were failures on the East Coast of the United States, or Chile, or Canton. They came to San Francisco to chase gold; they were gamblers. As a consequence of all this, the conventional values got left behind at the passport line.

The best story of all this is a guy named Emperor Norton. [In the late 1850s in San Francisco] Emperor Norton goes bonkers and declares himself “emperor.” He's a street crazy – every city has street crazies. What made San Francisco different was he started printing out his own money – “Emperor Norton banknotes” – and the people in the bars and the restaurants of San Francisco accepted them. Now, that's pretty crazy – crazier than him being crazy. And the reason they accepted it is because that was San Francisco.

And sexually, well, as late as the 1880s and ’90s, the city was still, like, 80 percent all male. It took a long time for the balance to be the conventional 50-50. Prostitution was effectively legal, both gay and straight.

[Much later in the city’s history] “hippie” introduced the idea that guys were wearing long hair and girls were wearing pants. The expectations of gender got scrambled. Just a few years after “hippie,” you've got Castro Street becoming the Valhalla of gay life in America.

GDB: In the book, you touch on all that. You also give a bit of history about the Compton’s Cafeteria riot in San Francisco, which preceded the world-famous Stonewall riot in New York – which is often (somewhat inaccurately) cited as the foundational moment in the LGBTQ rights movement. Three years earlier, a group of transgender women stood up to harassment by police in an all-night restaurant in the Tenderloin. That was an unprecedented moment of trans resistance to police violence, and it was a reflection of both the presence of sexual and gender-identity life in San Francisco as well as the will to fight for individual rights reflected in the political sphere.

That’s just one area where you touch on politics in The Last Great Dream. There’s also a good summary of the free-speech movement in Berkeley in particular, and some discussion of the anti-war movement. You included a lot of material about civil rights, which was one of the few political upheavals of the era that did not take root initially in San Francisco or New York City.

But the way I read your book, I felt your focus was primarily on the aspect of counterculturalism that encompasses the arts, intellectualism, and individualism versus conformity. You wrote mostly (though not exclusively) about the social aspect of this period of history rather than the political – even though, of course, the two are inseparably conjoined. Were you particularly focused on culture over politics? Was that purposeful when you approached the book?

DM: Well, it wasn't purposeful or thought out. All of those decisions were made, metaphorically, at the typewriter. I didn't know what I was doing; nothing was planned in advance. I finally located my beginning with Duncan and Rexroth in 1942. Eventually – very much later – I found my ending with Monterey [the music festival]. There was a way to write it so that all these forces came together, and psychedelic music is certainly more cultural than political.

The Republican Party changed E Pluribus Unum to In God We Trust in the 1950s. That's a very political event and real evidence of what was going on, so I talk about that, and then, of course, about the free-speech movement and the civil-rights movement. But to most people, that stuff is less important than the daily grind of getting and spending and feeding yourself and your family and so forth. I tried to get everything in – all kinds of impacts – so you have what people saw on television, what they were getting in their music, and then the impact of ’50s rock and roll, and then folk music, which was inherently political.

The end result is what you get, and that is primarily culture. The politics come in as the context for the culture. It obviously has an impact, but in the end, it's the social realities of daily life that, as a historian, I'm primarily concerned with.

GDB: I love that you ended with Monterey because it was the culmination of this entire countercultural explosion. By the time of Monterey, Haight Street was being overrun by runaways and money-making ventures, becoming something both more and less than what came before. The counterculture was, in a way, becoming the culture, at least for the young generation. Even so, Monterey was a reflection of the best elements of the counterculture that had produced it – great music and art, a peaceful gathering of people celebrating individualism and revolutionary creativity. And yet, it was also the prototype for music festivals that became, over the ensuing decades, a huge, highly commercialized industry. The irony is rich.

Take the Grateful Dead, for instance – or, more specifically, their legacy in terms of Dead & Company. My Facebook feed is full of people saying, “Oh, these 60th-anniversary shows should be free.” Other people are defending the price and the notion that all musicians deserve to earn a living, and the old idea of lambasting people for “selling out” is an archaic value. In a way, that conversation is a microcosm of the discussion about whether the counterculture became the culture.

I mean, when the Grateful Dead are celebrated with Kennedy Center Honors, and Al Gore, our former Vice President, had a poster of the Dead in one of his offices – can we say the Dead are still part of something we once called the “counterculture”?

Where is the counterculture today?

DM: If you have a home computer. If you take yoga. If you eat organic food. If you have concerns about the environment. If you want to defend trans people. Well, that's a good start. The cultural impact has seeped into our lives.

I teach this high-school class periodically – I do lectures – and these kids are studying the ’60s in high school because they're interested in it. I keep telling them that the reason they're studying this is because it's still part of their lives. These are issues that haven't gone away, won't go away. And, in particular, in a very negative way, these issues are more sharply in focus now. We have a president who wants to attack and dismiss the reality of literally a million people who are not conforming to his notion of male and female.

GDB; What's next for you?

DM; I don't have a clue. I have said this is my last book. I'm 75, and I take ten years to write a book. I don't know if I've got the energy, and I don't know of a topic. If I find a smaller topic that I could do quickly, I would. But right now, I don't have it.

I've had a wonderful response to this book. There’s a bit of a buzz about it. There's plenty of dumb stuff hippies did in there, or whatever. I like to think it’s good history and sympathetic – but not goo-goo-eyed.