Article Contributed by Scott Ward

Published on December 7, 2025

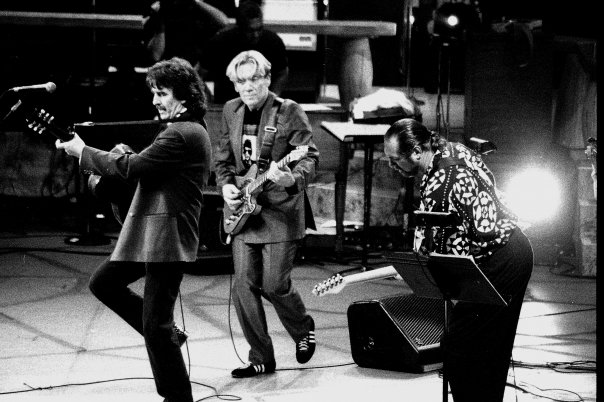

George Harrison, G.E. Smith, and Steve Cropper – Photo by Howard Horder

When I was 16, my hometown finally got HBO on our cable system. One of the first movies I saw was The Blues Brothers. In the infamous scene at Bob’s Country Bunker, Jake tells the club owner that they are the country and western band “The Good Old Boys,” even though they don’t really know any country songs. When the Blues Brothers Band launches into “Gimme’ Some Lovin’,” they are booed profusely, and the owner of the bar turns off the lights. Jake then comes up with the idea of doing the theme from Rawhide, to the delight of the rednecks in the crowd. During the song, Steve Cropper jumps to the front of the stage and plays a solo on his rosewood Fender Telecaster, producing a tone that I had never heard before.

The first records I bought were by Ricky Nelson, The Beach Boys, The Beatles, Jan and Dean, and Elvis. That movie turned me on to the blues and R&B—Sam and Dave, Wilson Pickett, Magic Sam, Aretha Franklin, Ray Charles, and others. That one singular scene from the movie inspired me to pick up the guitar, and I had the chance to tell that to Steve when we were recording together 35 years later. When I was in 9th grade, the Blues Brothers were popular on Saturday Night Live, and the album Briefcase Full of Blues was a hit record.

I learned to play guitar when I was 22, six years after The Blues Brothers had been released theatrically and later on HBO. My mother bought me a guitar and amp for Christmas in 1985—she paid $25.00 for both. I mostly learned songs from the ’60s: “The Letter,” “House of the Rising Sun,” “Good Lovin’,” and others. The first band I played with in my hometown would not let me turn up my amplifier.

In 1987, I enrolled at Gadsden State Community College in Gadsden, Alabama, and by chance I took a music class for elementary school teachers taught by legendary band director Billy “Rip” Reagan. One day he told us to bring an instrument to class if we played one, so I took my guitar. I had improved by that time, and after hearing me play he told me that if I would switch to bass guitar, he would give me a music scholarship. My family was rich by no means, so I was happy to have an opportunity like that materialize.

Playing guitar and playing bass are “two different animals,” as I found out quickly, but I worked as hard as I could and somehow was able to get that scholarship. When I was in the Showband, we played the “Blues Brothers Theme,” “Respect,” “Soul Man,” and many different blues and R&B songs. I started listening to bass players such as Donald “Duck” Dunn of the Blues Brothers/Booker T. & the M.G.’s, David Hood of the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, Rocco Prestia of Tower of Power, and Tommy Cogbill—even though I didn’t know who he was at the time. David, who invited me to come to Muscle Shoals about 25 years ago, told me about him. Tommy played bass on Aretha’s first records in Muscle Shoals, at American Studios in Memphis with Elvis on “Suspicious Minds,” with King Curtis on “Memphis Soul Stew,” and with Dusty Springfield on “Son of a Preacher Man.” He has never gotten the recognition he deserves.

In the following years I played in several bands in Gadsden and took care of my two daughters. In the late ’90s, I started going to Nashville trying to get something going musically, and on one particular day I met Steve and Garry Tallent of the E Street Band—on the same day. This would turn out to be one of the most important days of my life. One day I was in Gruhn Guitars playing Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” on an old Gibson acoustic. At one point I looked up and Joe Louis Walker was standing there listening to me play. Steve was producing Joe at that time.

A couple of years later, David Hood invited me to come to Muscle Shoals to hear his band The Decoys, where I would meet many of the best musicians and songwriters on the planet—Spooner Oldham, Donnie Fritts, Earl “Peanutt” Montgomery, Jimmy Johnson, and others. David was one of my biggest influences on bass and I was fortunate to watch him play live and in the studio for years. He also let me play a couple of his basses.

I recorded an album with Spooner Oldham in 2010 in Cullman, Alabama, which got me my first radio airplay, and it was during this time that Spooner and I became great friends. I did another album at Cypress Moon Studios in Sheffield, Alabama, which was the last location of Muscle Shoals Sound before Tonya Holly bought it from Malaco Records. This album featured Spooner, David, Kelvin Holly, “Funky” Donnie Fritts, and other Muscle Shoals legends. During the next couple of years, I had the chance to play bass with Kelvin and Will McFarlane, who was the guitarist for the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section since 1980 and who played guitar with Bonnie Raitt at the beginning of her career. We played some shows at the Harley-Davidson dealership in The Shoals, and to me, playing with these guys was like playing with the Allman Brothers. Will taught me a lot of blues songs—songs by Albert King, JJ Cale, Taj Mahal, Wilson Pickett. Having the chance to work with all these legends gave me the confidence to try and do what I wanted to do next.

In 2015, Chad Cromwell—the legendary drummer from Memphis who recorded and toured with Neil Young, Joe Walsh, Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and Mark Knopfler—was kind enough to allow me to book some studio time at his home studio outside Nashville in Primm Springs, Tennessee. I asked Steve Cropper to play guitar on the session and recruited my friend and frequent songwriting partner Mark Narmore to play keyboards. I had also asked David Hood to play bass on the session.

It’s really tricky trying to book a session in Nashville in February, especially if you are commuting. There was an ice storm that week and it also snowed later in the week, and I wound up having to reschedule the session three times to the following Saturday. There was snow in the forecast for Muscle Shoals that Saturday, but Mark and I left for Nashville with him driving my Honda CR-V. We hit some snow and ice when we reached Spring Hill, Tennessee, but somehow we made it to the studio. At one point Cropper called to check on us and told me that if he could get out of his driveway, he would be there. Over the next couple of hours, Steve lost cell service and got lost, but he finally made it to the studio.

We started getting set up for the session and I had to inform everybody that I would be playing bass since David Hood didn’t want to risk traveling to Nashville—which I understood completely, as the snow and ice were pretty bad. I had rented a Peavey Foundation from my friend James Counts at Counts Brothers Music in Muscle Shoals just in case something happened. I was really nervous because I had not picked up a bass in a few months. It’s kind of intimidating when you’re about to play bass with your biggest influence as a producer and guitar player. Steve was really down to earth, and I’ve always found him to be a humble, giving person, so he put me at ease. Chad Cromwell was really cool also—he had recorded and toured with my friend Spooner with Neil Young’s band. It also helped having my buddy Mark Narmore there—in many ways he is like his cousin Spooner and Barry Beckett: secret weapons that make any session go smoothly. I saw Steve’s custom-made Peavey Cropper Classic sitting on a stand and had the urge to ask him if I could play it, but I couldn’t get up the nerve. It would be at his home nine years later that I asked if I could play it, and I’m so glad I did. That is a memory I will cherish forever.

The first track we did was “You Left the Water Running,” co-written by my friend Dan Penn, FAME Studios founder Rick Hall, and Oscar Franks. That song has always been one of my favorites—Otis’ recording, and Dan and Spooner’s live recording from their album Moments From This Theater. I intended to use this track for the tribute album I was working on at the time, which would be released by Ace Records in 2016. Jimmy Hall added his vocal at Beaird Studios in Nashville a few months later. Chad’s drumming was really solid, and that track went pretty well and helped settle my nerves a bit.

The next track was an instrumental Mark and I had been working on in the key of E, which to me had a “Play That Funky Music” vibe to it, and Mark had added a chromatic rundown. I was sitting next to Steve looking at the chart, and at one point he asked me what chord to play—I think it was an Ab7. He said to me, “You’re a guitar player; what chord do I play there?” It is really something when you are as nervous as a cat in a room full of rockers and a Rock & Roll Hall of Famer—and one of the best producers in the history of the genre—asks you what chord to play. But that’s how Steve was—he was just an old country boy from Missouri who liked to hunt and fish and treated everybody the same. Spooner has that same quality.

I did get a rise out of Steve when I threw in some slaps and pops on the bass when we were tracking that one. He just stopped playing and said to me, “I hired a bass player for a session once and I told him, if I wanted that, I would have hired another guitar player…” I could have crawled under a rock if there had been one in the studio. I told him I would play it straight, and that’s what I did. I tried to channel David Hood, Duck Dunn, Tommy Cogbill—maybe a little John Entwistle—and it was a lot of fun. We had a good laugh about that over the years. The next day I emailed him and apologized for playing like that, but I told him that was what I was feeling. He told me to “always play what you feel.” He also told me he enjoyed the session. Chad’s old studio had the feel of an old farmhouse and he told me it was kind of like jamming in a garage—something he said he hadn’t had the chance to do in a long time. Most of what he had been doing were overdubs at his studio in Nashville.

After we finished those two tracks, Mark called an audible and decided he wanted to do a third track: Percy Sledge’s “Take Time to Know Her.” Steve loved Percy so much that he once said in the ’60s that he didn’t care if he got paid or not—he just wanted to work with him. Mark is a master at writing number charts fast, and he wrote it out in about five minutes. This one was really fun—I tried not to play too many notes on bass, but Duck Dunn was fabulous at playing really busy basslines even on ballads or slow songs—listen to his parts on the Blues Brothers’ “She Caught the Katy.”

After we finished the tracks, Steve just sat there in his chair, drew a heavy sigh, and said, “I wouldn’t have done this for Otis,” referring to his good friend Otis Redding and all the trouble he had getting out in the snow and ice on a Saturday on top of everything else. On one hand, I was kind of relieved that I had made it through the session with no major gaffes, but on the other hand, I didn’t want it to end because I realized that days like that are few and far between.

After that day, I would go see Steve when he did shows in Nashville, and I never got tired of hearing his stories—how Booker T. & the M.G.’s “Green Onions” came to be, how he and Otis had written “Dock of the Bay,” using a cigarette lighter as a slide on his guitar intro on Sam and Dave’s “Soul Man,” and many others. He said Otis had called him to come to his hotel room and when he arrived Otis said, “Get your guttar,” which is how he pronounced it. Steve said that Otis always tuned his guitar to open G. After Otis and most of his band died in the plane crash in 1967, Steve finished “Dock of the Bay” with a heavy heart and added the sounds of waves crashing and Otis’ whistling track. That song has been covered so many times over the years—most notably by Michael Bolton and Sting.

Steve also told me the story of how a then-unknown Jimi Hendrix drove his VW down from Nashville to Stax on a Saturday when Steve was the only one there. He was busy mixing some tracks. He said that he brought Jimi in and Jimi grabbed Steve’s guitar, flipped it over to play left-handed, and showed him what he had played on Don Covay’s “Mercy Mercy” at Atlantic Studios.

He also told us some great stories about how he became a member of the Blues Brothers Band, the filming of The Blues Brothers movie, and being in a hotel with Booker T. & the M.G.’s while Woodstock was happening—but never performing because Al Bell of Stax Records didn’t want to fly in a helicopter. All the bands and artists who performed at the festival were flown in by helicopter. Steve also told us who threw the beer bottles at the chicken wire during the aforementioned scene at Bob’s Country Bunker—Steve said it was Willie Nelson and Sissy Spacek, who were both on the lot while filming Honeysuckle Rose and Coal Miner’s Daughter, respectively, and were recruited by producer John Landis.

Steve said that when he got the call from John Belushi about playing guitar for his new blues band, he was in the studio producing Robben Ford—and he turned him down. After a few minutes, Robben told him that if he didn’t call John back, he was going to. Steve also said he had loaned Bobby Whitlock the money for a plane ticket to fly down to Miami to join Derek and the Dominos. The last time I saw Steve, he told me that Bobby was the only one he had helped over the years who had paid him back.

Steve also told me about playing on both John Lennon and Ringo Starr’s solo albums. I never knew which track he had played with Ringo, but one day I heard his cover of The Platters’ “Only You,” and I recognized Cropper’s guitar parts immediately. His playing on “Who’s Making Love” is also instantly recognizable.

In addition to being one of the best session guitarists ever, Steve was also one of the best producers in the world. He produced albums by Jeff Beck, John Cougar (Mellencamp), Tower of Power, and a great tribute album for the band that influenced him the most when he was growing up: The Five Royales. It was called Dedicated: A Tribute to the Five Royales and featured Steve Winwood, Delbert McClinton, Dan Penn, Bettye LaVette, and others.

Wilson Pickett is one of my biggest musical heroes, and I came up with the idea to do a tribute album for him in 2016. I had cut a few tracks, and then I had a bad car accident which could have killed me and sidelined me for about nine months. I did the bulk of the recording in Muscle Shoals in 2021, and I asked Steve to do a track. He wanted to do “99 ½ Won’t Do,” which he co-wrote with Wilson and Eddie Floyd and which appeared on the album The Exciting Wilson Pickett. I hired the best musicians I could think of—Jason Isbell’s rhythm section of Chad Gamble (drums) and Jimbo Hart (bass). Chad’s brother Al, keyboardist for St. Paul & The Broken Bones, played piano. Steve added his guitar parts at his studio in Nashville, and I hired Jimmy Hall to do the vocal at Wishbone Studios in Muscle Shoals. The tribute album for Wilson was released by Nola Blue Records in 2024, and that track is probably the one I’m most proud of. Even though Steve’s health was failing this year, that track was on the first ballot for the Grammys in the Best American Performance category. Even though it didn’t make the final ballot, I hope he was proud to see that. As usual, he didn’t charge me a dime for playing on that track.

I have a couple of unreleased tracks I did with Steve, and I have one that Mark Narmore and I co-wrote with him in 2024 that I hope to finish soon. I’ve never had the death of a musician affect me like this—it’s as if one of my family members has passed away. He had such a profound impact on me. I know I will miss him every day. I will listen to his great body of work, and I will listen to his isolated guitar tracks from the sessions he did for me. I will play my Peavey Cropper Classic, one like the one he played at his Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction. But most of all, I will remember what a great man he was, and I will always treat people the way he did—no matter what their place in life is.

No other posts from Scott Ward.