When one first hears Zero, whether it was back in the 80’s or last fall, the immediate thought is, “How have I never heard about these guys?” And then considering the next thing you’ll want to do is share it with a friend, you’ll once again wonder, “How have I never heard about these guys?” Regardless of whether you haven’t heard of them, or haven’t spread their music to your friends enough, with the release of Naught Again, there is no better time than now to dive into the ocean of phenomenal music that is Zero.

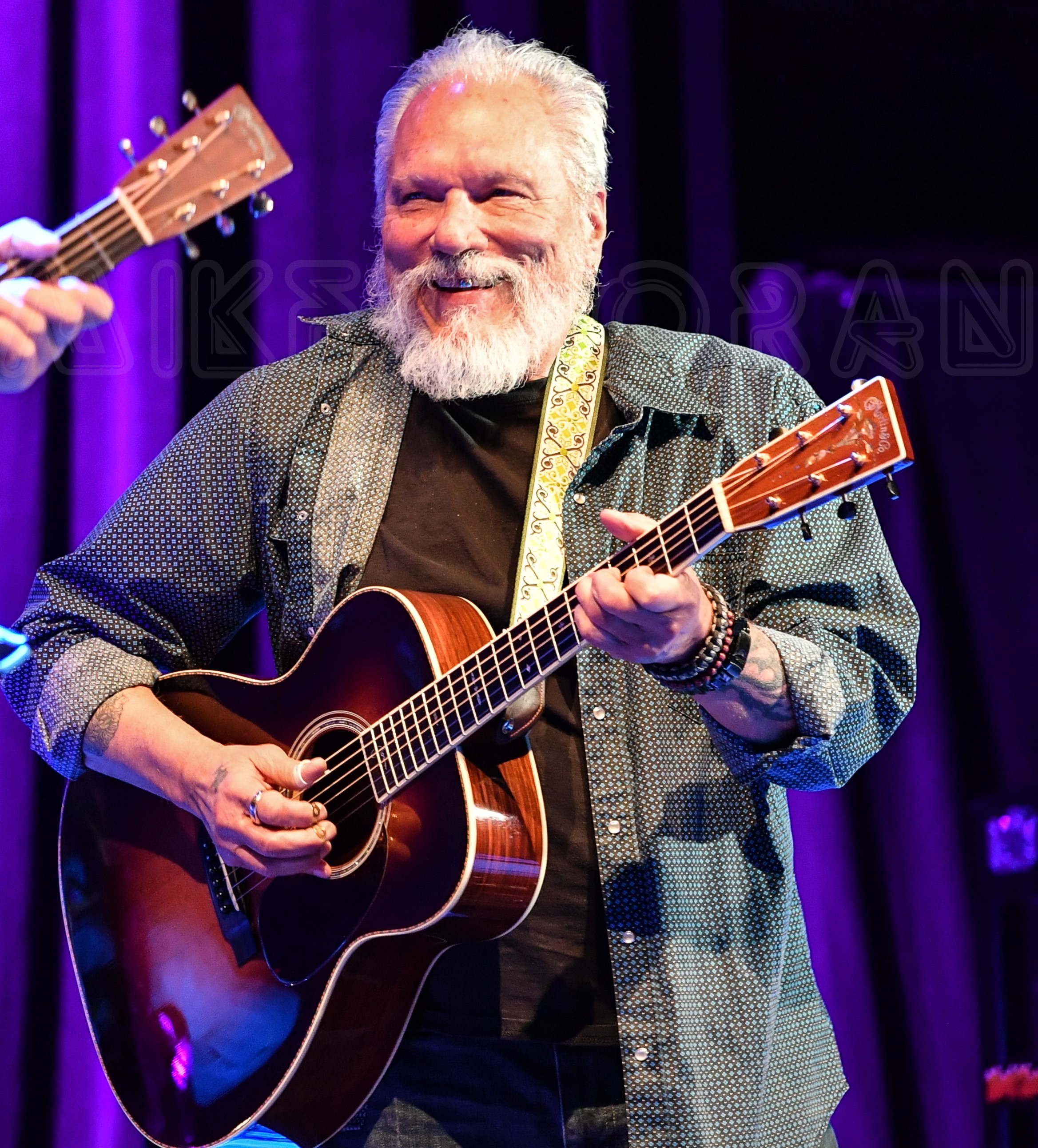

Considering the hotness of Zero’s selected song release from this 1992 Great American Music Hall three-night October run, Grateful Web couldn’t resist the opportunity to chat with the two founding nuclei of the highly innovative group, Steve Kimock (guitar) and Greg Anton (drums). Following their previous release from the same October shows, Chance in a Million, Naught Again reminds us that we’ll have Zero to lose if we don’t take a closer look. And even though Zero (as well as Kimock and Anton) have a long history, have accumulated countless accolades, and have introduced a new level of musical understanding to Humanity’s very being, one can still say to many, “Zero is the greatest band you never heard.” Robert Hunter, songwriter for Zero, who’s also featured on the album providing a “prologue” and “epilogue” during the show, once stated, "Zero can put the whammy on the crowd. I’ve seen a lot of crowds in my life, but they can do something that I've never seen before." What more need be said?

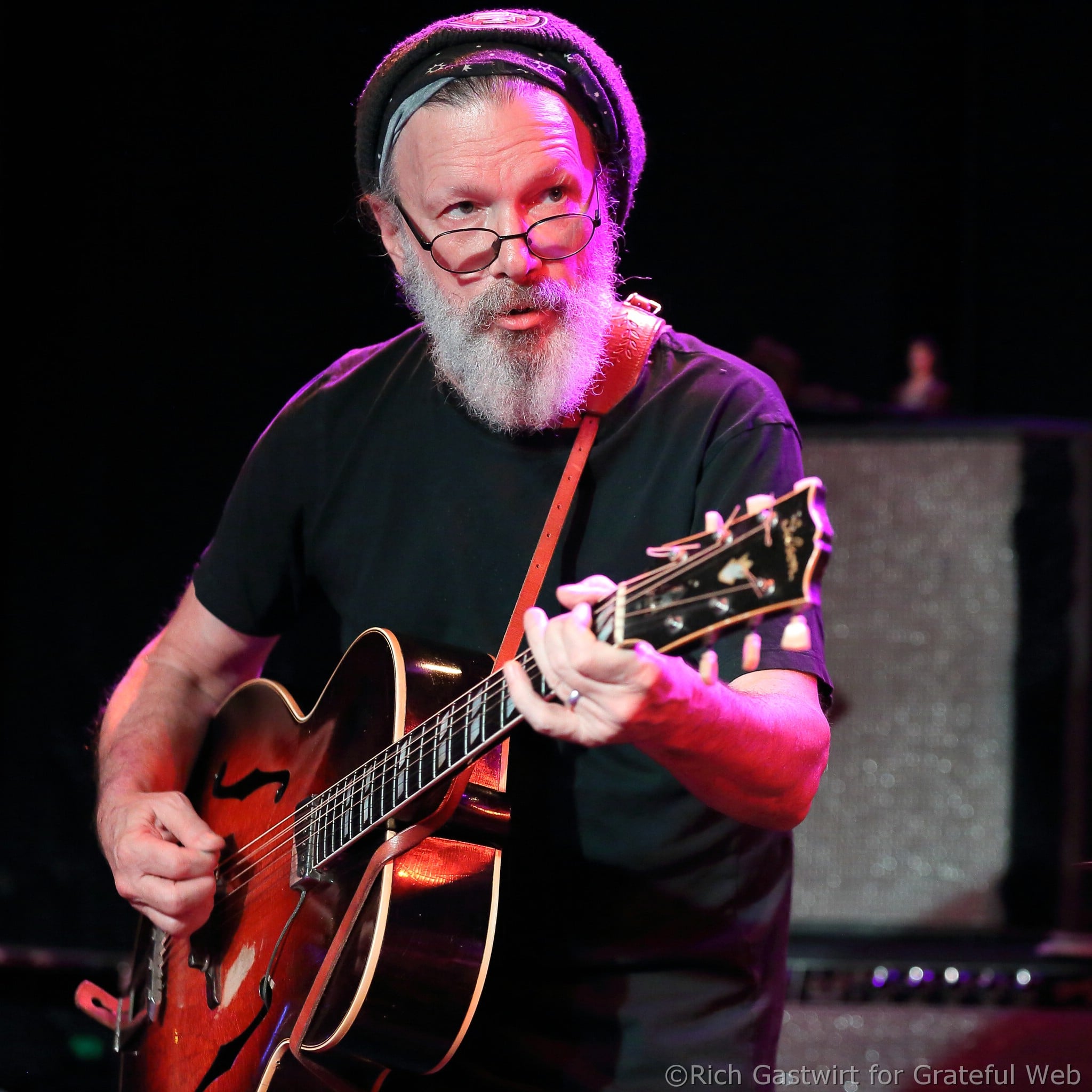

Apparently a lot, as you’ll read in the following interview. Amongst humorous stories and anecdotes, Steve and Greg talk of how the art of listening is paramount to a good musical connection and how the art of playing is found in losing one’s self to the sound. Chatting about how the moment is created by what we each bring to it, how we can each be an artist in what we bring to every encounter, to every chore, even to the formation of our own minds, one realizes the joy found in making music with the infinite moments of time that become our lives. Steve goes on to explain how he doesn’t “make” music, but rather finds his way within the musical forest, stating how one does not create the wilderness when they walk through it but rather discovers it. One’s sound doesn’t just come about by mere talent or gear, but rather from the understanding from which it arises. And once you realize where Steve Kimock and Greg Anton are coming from, the music only gets better. Speaking of the dangers of being a musician, one wonders the length many will go to “silence the noise” so they can feel a true connection with the timeless now of things. Speaking on his novel, Face the Music, Greg surmises that motion is a singular objective truth we can all agree on, the pure expression of which is music.

A slow revolving door of monstrous talent, many of which have now passed on, Naught Again features the likes of John Kahn, Pete Sears, Vince Welnick, Bobby Vega, Martin Fierro, Nicky Hopkins, Liam Hanrahan, and Judge Murphy, along with original song lyrics by Robert Hunter. Zero has also attracted many “guest” musicians from today’s most talented and awe inspiring players, including Merl Saunders, Melvin Seals, Holly Bowling, John Cipollia (now a regular) and too many others to list. Recorded by Grateful Dead’s very own, Dan Healy and Don Pearson, the quality of the show equals the quality of music.

With a mind-opening version of “Little Wing”, we not only see the reach and breadth of Jimi Hendrix, but also Zero, who can take such a classic piece and make it flourish with Zero impact. Along with other select covers, like the awe-inspiring version of Greg Anton's and the Dead's Donna Jean Godchaux's "Golden Road, or The Who’s "Baba O’Riley", Zero fills the mind with both original play and original tunes that rock the soul. Hell, let me just say this straight up. Naught Again is jam-packed full of just smoking, mind-bending, incredible music that quietly draws you in and leaves you feeling dreamy, lost to the world that once was. Owning this show immediately makes you 20% cooler. My Little Pony reference aside, (friendship is magic) you’ll find yourself shaking your head in awe at what these guys are doing. Steve Kimock has definitely come into his own over the years and is certainly one of the most creative, innovative and note-worthy guitarists of our time. And that’s saying a lot considering all the incredible guitarists there have been in our time. With the release of Naught Again, there is no better time than now to dive into the ocean of phenomenal music that is Zero. Tour dates to be announced soon.

GW: Hey guys! Great to talk to ya. We’re getting together today because you are releasing some songs from The Great American Music Hall ’92 shows, called Naught Again. It’s a great set of shows. Why have you guys decided to release this now?

[silence]

Steve: Don’t everybody talk all at once. [laughter]

GW: Should I direct questions to one in particular?

Steve: Direct your questions for factual answers to Greg. I’ll handle opinion and rumors and innuendo and stuff like that. [laughter] Greg’s a lawyer. He knows all the answers to actual evidence-based stuff. He’s ambidextrous.

GW: I thought that was a bad word.

Greg: What? Evidence.

[laughter]

Steve: Well, evidently. [more laughter]

GW: I knew I had the right lawyer when I noticed he was wearing a Jerry Garcia tie.

Greg: [laughs] Yeah.

GW: So, Greg. How did you guys decide to release this, and why now?

Greg: Here’s what happened.

Steve: This is my story and I’m sticking to it.

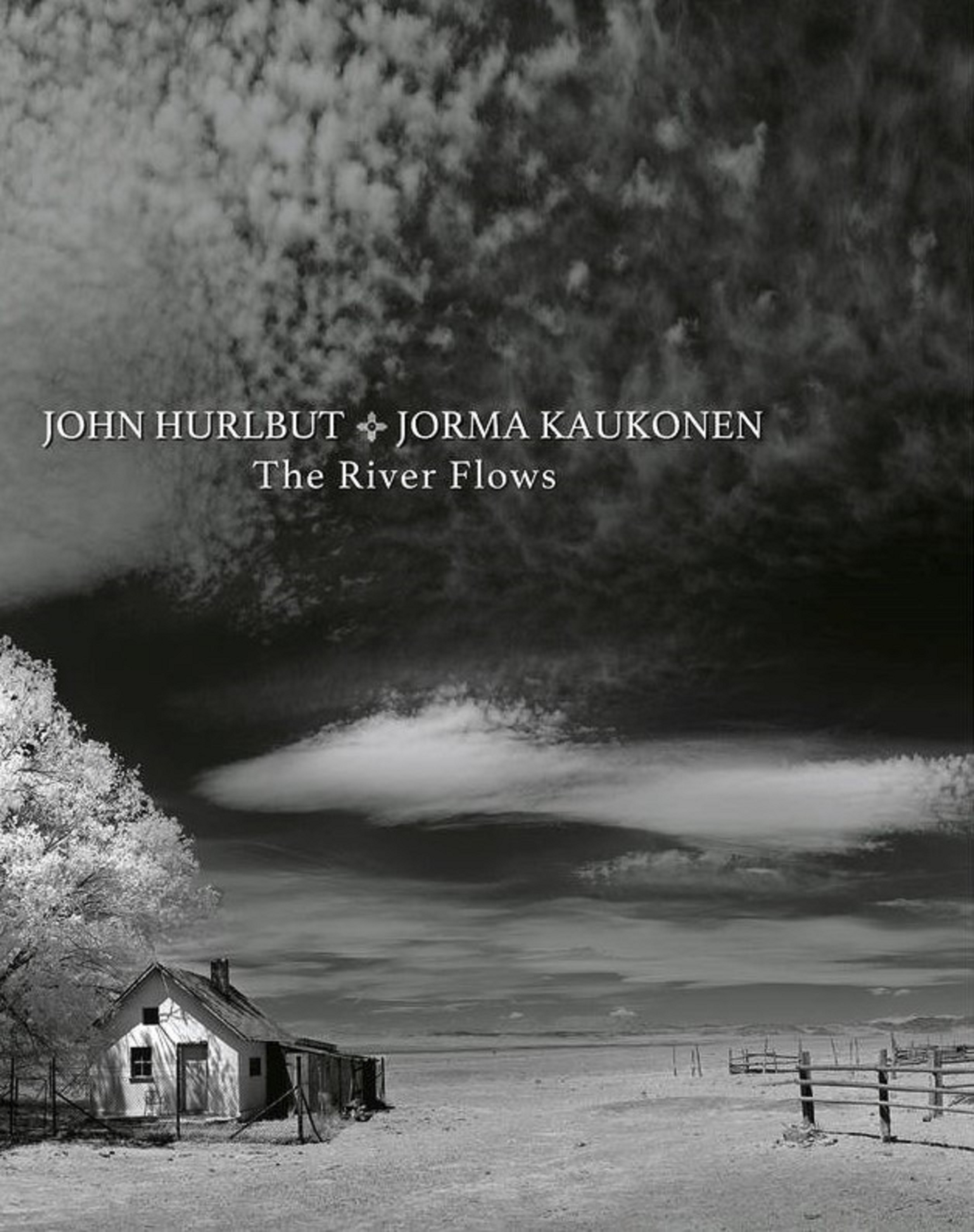

Greg: In 1992 we played three nights at the Great American Music Hall. We had been up to then mostly an instrumental band. Then we started working with Robert Hunter who was putting lyrics to our music. So we decided to get together and record three nights at the Great American Music Hall with a bunch of friends, and made a record called Chance In A Million. About a year ago, our audio engineer, Brian Risner called me up and said, “Let’s remaster Chance In A Million.” And I said, “Good idea.” He says, “See if you can find me a couple of bonus tracks.” And so I went back and listened to the original recordings and found a whole ‘nother record, another double record of music I thought was worthwhile putting out. And so here’s the record, Naught Again.

GW: I’ll just have to ‘fess up. I had a hard time coming up with questions for you guys because I kept getting lost in the music. Next thing I know, twenty minutes would go by and I’m just listening to music. Then I’m like, “Aw, man. I’m supposed to be coming up with something to ask these guys.”

[laughter]

Greg: Well, let me ask you a question. After listening to a Zero record, say you’re talking to a friend, and said, “Oh, I listened to a record last night.” And the friend said, “Oh yeah. What kind of music?” How would you describe it?

GW: I was talking to my wife about the music because it kept leaving me feeling funny. What would I say? Lost and dreaming. It was very appealing, the way it left me feeling, almost as if I had gone to another place, then it was like you’d wake back up and go, “Oh shit. I was dreaming.” It felt very ethereal the way it drew me in. And Steve, you have such a light touch. It’s really beautiful. And if it says anything, I did send the Mystic Theatre performance of “Tangled Hangers” to a friend of mine this morning. I was like, “You gotta listen to this. This is great.” And of course another twenty minutes went by and I’m like, “Oh shit. I’m supposed to be coming up with questions.”

[laughter]

Steve: Well, I was going to tell you too that I think it’s easier coming up with questions sometimes than it is answers. There’s that.

GW: [chuckles] I hear you. How about this? The way your music left me feeling, I wondered: When you guys are onstage do you get lost in the music too?

Steve: I think some of us probably do. I think you’re using a good word. Maybe you’re coming at it from a slightly different angle than I would because people do think—like the audience sometimes thinks—that people are making music or something like that. I don’t think you make music so much as find your way in it. So, it would be appropriate to be lost as you’re exploring new territory, not knowing what you were going to find. You know, like if you just went out into the woods and went for a walk, went for a big hike in the wilderness. Maybe you don’t know where you’re going, or what you’re going to see, but you’re not creating the territory as you’re walking. [laughter] You know what I mean? It’s just like you’re discovering it because it’s there. I think the music thing is like that. So it would be appropriate to be lost if you were trying to find your way. And it would also be appropriate to understand that the way you would find yourself is to just be entirely in the moment. Then there would be no you before, or you later, to be lost, you know?

GW: Yeah, I follow that.

Steve: You actually found your way when there’s no time. You know?

GW: Yeah. Absolutely.

Steve: No more sensation of passing time.

GW: So you’re realizing what you’re playing as you play it.

Steve: No. [laughs] What makes you think that?

[laughter]

Greg: I do my best to listen to the music rather than be thinking about everything else. Or be thinking at all. I’m listening to the music as its happening. I’m not always successful in doing that but that’s my goal, to listen to the music that’s being played while it’s happening.

GW: While it’s happening, which keeps you very in the moment.

Steve: Yeah. I mean, it’s just there. There’s a million things that can distract you. There’s issues with everything. There’s issues with every single person on the fucking stage. There’s issues with every single person in the audience. There’s issues with sound. There’s issues with security. There’s issues with what you ate before. There’s issues with the lights. Issues with the fucking monitors. Every single thing can be a potential issue. So we’ve discovered over time that the answer is . . . drugs.

[laughter]

Steve: And if you can get fucked up enough and not notice any of that shit, and maybe, just maybe, you can find your way. That’s not true. That’s not true. I shouldn’t say that. In all seriousness you wonder why people—I mean, just like historically, it doesn’t matter who it is, whether it’s Garcia, or Charlie Parker, or John Coltrane, or fucking Keith Richards, or any of these people—why they got as high as they did is because it’s really hard to tune out the noise. Depending on what kind of person you are, what kind of personality you are. Some people are just more uptight, some people are more open, or whatever the deal is. The whole idea that you’re going to go out and play some music and get good at it somehow, it’s kind of dangerous work. I’m not going to name any names now, but there’s a bunch of people on that stage, that night, that it’s dangerous work for.

Greg: Yeah.

Steve: They did great with it but it caught up with them.

Greg: I try to tune out the noise and listen to the sound—It’s communication at the speed of sound between the people on the stage talking to each other, and I’m trying to listen. My wife is a psychologist and she says there’s seven kinds of listening. I’m not exactly sure what that means, but I know for myself there’s different kinds of listening and I do my best to reach the highest quality of listening.

Steve: We’ve talked about this before. In the cognitive side of the music, there are these things they call “presumed listening modes”. There are presumed listening modes that are specific to trained listeners where you’re listening for cues, or you’re listening for similarities in some other pieces of music, stuff like that, or listening for timbres, or influences in the music that might evoke some other artist. Something like that might be shared with an untrained listener. But then there’s stuff that everybody in presumed listening mode can share. A sing-a-long, where everybody is moving together. You can be upbeat, trained or untrained, to experience that nostalgia, remembering motions from past concerts where your songs get all different kinds of presumed listening modes.

So I don’t know if there are seven, although seven is a good number for upper limited information channels that people can deal with. My own impression is that you don’t really listen in more than one mode at a time. So if you’re up there and you’re listening for a cue— like the guy tells ya, “Oh, you’ll hear it.” Then you’re up there going, “What am I even listening for?” [laughter] At that point, you’re not in the fucking moment. You’re not doing anything that’s got anything to do with getting to the good part. You’re like, “I’m going to screw this up.” You’re like, “Where’s my cue?” Right? [more laughter] That’s an entirely different kind of listening.

And to continue to elaborate on Greg’s well-taken points about what’s going on onstage—as if it were communication between people, as if music were a language—it’s fair. People look at it that way, and I understand why they do. There’s another way to look at it that I am personally more likely to find myself in, which is, I play with the music not the person. I don’t play with people. I mean, they’re up there. I’m dealing with them on some level, but it’s not the person I’m trying to play with. It’s the result that I’m trying to—I don’t play with it as much as find my way in it. And when I do find my way in it, I’m only responsible—I feel I’m only responsible—to provide some kind of balance based on my own aesthetic. So I’m not really trying to play with Greg. I’m trying to interpret whatever noise he’s making as too much or two little, and I go, “I should put some more stuff in here because it needs something here.” Or, “Ooh, that’s enough. I better not put any more.” You know what I mean? Just like in terms of density, matching dynamic intensity, stuff like that.

A whole bunch of what happens onstage in the music are really big, dumb ideas, like matching dynamic intensity. [chuckles] It’s like, “Oh, he’s playing harder, I’ll play harder. Oh, he’s backing off, I’ll back off.” Or, “It feels kind of empty, I’ll do some more.” Or, “Ooh, that’s way too much I think I better like stroll.” That kind of stuff. But you don’t really do that with a person. You do that with the music. You don’t really do it by trying to, “make music”, or to say something—you’re just balancing some aspect of it, or some part of the overall effect, and it’s not really micromanaged. When you try to micromanage something you can’t do anything. You can’t do something about every beat on a high-hat, or how much the low woofer is eating your low string, or something like that. Just forget it. You just got to deal with it.

GW: As a fan, I have two ways of listening. The one is just surface, where you’re tapping a toe and singing along like you mention. Then there’s the note-for-note ride where you dive down into the ocean of it all, where you catch the conversation, the one responding to another, or one setting up a sound and the other finishing it type of listening that the note-for-note ride gives you.

Steve: I do think that I can listen to some stuff like that, but personally, I think a lot of my listening is just some overall affect of the thing, of just some aggregate, emotional type of thing I listen to. It’s hard for me to get super specific with anything unless I sit down and force myself to go, “I’m going to figure this part out.” [laughs] That kind of thing. Which I’m not crazy about. That’s not my favorite part about doing this, figuring out what somebody else did on some other fucking chord or something.

Greg: Hey David, I want to say that I’m reminded on this conversation, I find it fascinating. I’ve been playing with Steve for about forty years. He’s been standing on the stage about ten-feet away for forty years. I’m trying to figure what’s going on and I’m reminded of the interview I read with Lindsey Buckingham from the band Fleetwood Mac. People are familiar with the complex relationships they had, and in this interview in Rolling Stone magazine with Lindsey Buckingham, the guy got to the end of the interview and he says, “Well, what’s going on with Fleetwood Mac? You guys been talking about getting together and doing some playing?” And Lindsey said, “You don’t get it about our communication in this band. Our communication is: I do an interview with Rolling Stone magazine. Somebody else in the band reads it. And that’s how we communicate.”

[laughter]

Steve: That’s the way it is.

GW: Well, at least somebody else read it.

Steve: Not to introduce any disparaging energy to the interview but I don’t ever read any of this stuff, or listen to it, like the press part of it.

GW: Well, good. Now I don’t have to worry about it being good then.

Steve: No. You do have to worry about it being good. That’s the only thing I was going to say, but that doesn’t have anything to do with me, that has to do with you as a writer.

GW: It does.

Steve: I want your commitment to this thing to be my commitment to this thing. You know what I mean? Like I said at the beginning to Greg, I said, “Hey. Just these are the facts, your honor. Just like stick to the facts of the thing.” I don’t have anything. I got no facts. There’s no facts in this for me. There’s no truth in this for me. There’s no objectivity. It’s all just how I feel in the moment, and all I want to do is make art. And that’s all you should want to do. Cut the bullshit and make art out of it that you enjoy doing and that you think your readers are going to resonate with. It doesn’t matter what you do with my words. It doesn’t matter what you do with my talking about my art. It’s bullshit. It matters what you do with your art. So I don’t care what you do with it. I just care that you feel good about making art in this process.

GW: Thank you. That makes perfect sense to me. In regards to earlier when you were talking about “issues” of this person, that person, the gear, what you had for breakfast—I call those the conditions of things. The conditions form the moment. Conditions will come together in one way and certain nights are really hot, and other nights are not so good depending on how the conditions come together to form that moment.

Steve: Exactly.

GW: And it’s the infinite conditions that exist and form each moment that I try to bring into my writing so as to illuminate how moments come about, how thoughts arise, how music is played.

Steve: And we’re not in control of those. We’re at the affect of that stuff. Just like me and Greg onstage are under the affect of all those conditions, and you with your writing, with everything else that’s going on, with the deadline, the weather, every single thing. Yeah, I get it. I’m just encouraging you because I don’t need to go back and review what you wrote. “Oh, did he get this right? Did he say what I said? Do I think that he understood?” [laughter] It’s like, “No.” That’s not fair to you, or your readers. Your readers want to read something cool. When they see the band, they want to hear something cool. Just give them something cool. It doesn’t matter what it is as long as it’s cool. As long as you think you know well enough. You know what I’m saying?

GW: Yes. My words come from the inspiration. If I’m not inspired, I have no words. I won’t do articles on stuff that doesn’t inspire me because I can’t make up words and give somebody something cool. I’m a terrible writer if I have to make it up, but if I’m sitting here and listening to your music, I actually get my words from your music, they’re an illumination of a reaction in me.

Steve: You should tell that to the people reading this stuff. You should tell them in your own words that you talked to these guys, and the point Kimock wanted to make is that the whole idea is making some art, creating something, finding your way in it—being able to express and to get enjoyment from consuming that art or that product or being around it. That’s it. And to encourage the people that are reading it to do stuff and be artistic with it. Like if you have to wash the dishes, bring something. Everything, too. Bring something to it.

GW: I’m totally on page with you.

Steve & Greg: Yes. Yes. [laughter]

GW: Even with dishes. I often wonder why I like washing plates but not forks. It’s just a different motion. So why is there a want and a not want there?

Greg: I’m there with you.

GW: Speaking of all that people can bring to it, you guys have drawn so many different players wanting to play along. Obviously you guys have a bunch of musician friends, but apparently a lot of people want to sit in on the Zero style of music.

Steve: I think we just have a hard time saying no to people when they ask us to sit in. [laughter]

GW: Great answer. [laughs]

Greg: My experience of people sitting in with Zero that happens so much is somebody will sit in, say for example, a guitar player or keyboard player, or somebody, and they sit in and they go, “Oh my god. It’s a good thing I’m here tonight because there’s this big space, there’s this big hole in the middle of Zero [chuckling] and it’s a good thing I’m here to fill it in. I don’t know what they would have done if I didn’t show up.” [laughter] I think we have a lot of space in our music that we intentionally leave there.

Steve: There’s a lot of space that’s filled too, but to the extent that we are leaving space in the music, it’s because obviously we leave space together. That’s also part of the playing thing, the matching dynamic intensity and just being in the sound together long enough to appreciate there’s some kind of density of sound, an amount of activity there that can take place, that makes sense, that you’re comfortable in, that serves as both a resting place and a launching pad. There’s a way to go about it that leaves the next move open, and that’s tricky for people. Most people don’t appreciate it, at least as fully as I do, that sometimes it’s better when you’re not there. I don’t have a problem with that. Sometimes it’s better when I’m not there.

GW: And you’re man enough to admit that.

Steve: [laughter] Oh no. I totally get it, man. I listen to so many fucking great records that I’m not on, so many that are way better that I’m not there. That’s just the reality.

GW: [laughter] How did you guys meet? Was your musical connection pretty immediate? For forty years you’ve been hanging out, so there was obviously something that happened originally with you guys.

Greg: Well, there was a big space before we met. [laughter]

Steve: We both like cars. That’s all it is really.

GW: Oh. Not what I was expecting.

Steve: It’s not what I was expecting either. What the hell? It’s true. We’re riding in the car, and Greg’s going really fast. Then he goes, “You like going fast?” And I go, “Yeah, I really like going fast.” [laughter] Then we just drive around going really fast everywhere. I saw a guy Greg, saw a guy drive by up here. It was like a silver blue, ’64 or ’65 convertible Corvette, and the sound of it as the guy drove by, and I was like, “Fuck. That was a cool car.” Greg used to have this very cool Corvette, blue Corvette he’d drive around.

Greg: Yeah. I had a ’64 Corvette for about 25 years. Just for example, for this record, for these recording sessions, I’d pick Steve up and we’d drive to a musician’s house and teach him some songs. We were driving all over the Bay Area.

Steve: I had one of the coolest experiences I ever had—just going back and forth to the ranch from where I lived. I lived in Sonoma County, and where we had our rehearsal was in Western Ranch. Along the way, a lot of my really great experiences with the band, and with the people, involved automobiles. I’ll relate two of them. I was driving when we first started. I got the car from Greg because it was sitting around at the Ranch, a ’67 Mustang. It was blue and it had a gold trunk. It was a six-cylinder, three-speed, ’67 Mustang. It was just barely big enough to get me and all the bass player’s stuff into. Two fifteen cabinets in the backseat, and two Boogies in the trunk, and a bunch of guitars and cables and bags and all this stuff. And the Ranch was way, way, way out like in the sticks, out by the coast by Samuel P. Taylor State Park in Northern California. And the last stop before you were in the woods was a 7-Eleven in Petaluma.

We stopped at the 7-Eleven, Steve Wolf is the bass player. He gets the 7-Eleven coffee, just a giant 7-Eleven coffee. It’s like a 90 ounce coffee. It’s a huge fucking thing—black—filled to the top of this flimsy paper cup with the little plastic lid, and we go tearing off down the road. Zoom, zoom, zoom. It’s like so twisty you have no idea. There was this one place where there was this little hill, and then this little off-camber kind of fall where the road turned one way and tilted the other way. There was always this cattle crossing sign at the top of it. There’s never any cows. So I come over the top of this hill at like seventy miles an hour on this little road, and sure enough, I get to the top of this hill and there’s nothing but cows across the road. Literally, a bunch of cow-hands who are going, “Oh, no, no.” I’m in full suspension droop with a car full of shit, right. I’m trying to put on the brakes, and there’s no brakes. The wheels are off the ground and the car is sideways. I’m hurtling through this herd of cows down this hill looking through the side window going fully sideways, and Steve Wolf takes the lid off his coffee, takes a sip, and puts the lid back on. [laughter] Right? And I was like, “Holy shit! Was that cool.” Then, BANG! We’re up against these cows, up against this fence, and this cow is like trapped against the fence, and we’re trying to push it out, and it’s all wiggling around and stuff like that, then it pushed us out of this ditch. The cows were all okay, I guess, and we continued to rehearsal.

[laughter]

Steve: But that is not my final suspension droop story, because really the very best experience in my entire life—you’re wondering why I’m telling you this, this is why. Greg doesn’t even know this. I won’t tell this to Greg. He doesn’t deserve a fucking story like this. [laughter] We were way up in the Sierras. I don’t even know why. I have no idea what we were doing up there. We were so far from anywhere. It was really late at night. We were going somewhere, and we were going really fast. When we would go someplace, when we would get off the exit, there would be this screeching tire smoke, and when we would finally come to a rest halfway out into the intersection where the stop sign was, you’d be followed by a cloud of dust and smoke and pebbles, you know, like people wailing. So anyway, we weren’t going Mustang fast, we were going Corvette fast. It was the middle of the night and we were going up this hill, and the sound of that motor, a 327, in that Corvette, accelerating up hill, Vrooom! [makes car sound] and we got to just the top of the hill and the car just kind of lifted off the ground just that little bit. The clutch goes in and the gear shift is in neutral for just a second, and all the sound from the road and the car stopped and all the sounds from the night just flooded in, the air, the crickets, and just hung there for just a second, a frozen moment, and then “Roar” I gun it hard on the other side. It was the greatest thing ever.

[laughter]

Steve: So anyways, it’s shit like that.

GW: That makes it all worth living.

Steve: It’s got nothing to do with the fucking microphones, like all the rest of the stuff makes everything worth doing. The actual doing the music thing is a fucking pain in the ass.

[laughter]

GW: That’s great.

Greg: That’s a hell of a story, man. That was great.

Steve: You know, the other stuff is fun. It’s the occasional cartwheels in the dressing room that make it worthwhile.

Greg: I’ll tell you—he was talking about Steve Wolf, which was one of our very early bass players.

Steve: He was our first bass player, I think. Wasn’t he?

Greg: I don’t know if he was our first.

Steve: I can’t remember.

Greg: Anyway, Zero’s doing a gig with the Neville Brothers, and the Neville Brothers play with a bass player on the right side of the drum set, and we play with what’s traditional, with the bass player on the left side of drum set where the high-hat is. So I go up to Steve, and I said, “Hey. Those guys keep their bass player on the right side and Steve likes to play by the high-hat.” He says, “But then we’d have to move all the equipment around and they want to leave it like it is.” And I say, “What do you think we should do? What do you think Steve Wolf is going to want to do?” And Kimock says to me, “If you took Steve Wolf—if you took a high-hat stand and put it out in the middle of the desert, Steve Wolf would go stand next to it.” [laughter] He says, “The bass goes on the left. That’s it.” I always remember that line.

Steve: It’s true. You could put the high-hat out in the middle of the street and he’d be right there. [laughter] He’s high-hat trained. He’s so old school.

GW: Mouse to the cheese.

Steve: We had a long spell of what I like to think of as traditional bass players. I think that’s partly Greg, partly the music, it’s partly me, but we really gravitate to four string Fender bass players. Like back in the day, if you played bass, you played fretless, acoustic bass. And then later on there was like—“Ooh, Fender bass”—and there was a precision bass that had frets, that actually played precision notes. It wasn’t fretless. So the idea that there was “Fender bass”—that was a thing. And that’s still the thing that’s a comfort zone for us.

GW: That’s what Pete’s (Sears) playing.

Steve: Yep. We like Fender basses and Hammond organs. We just like the traditional stuff as much as there’s all this non-traditional things that you’re trying to incorporate. For the most part we’re kind of a traditional rock and roll band.

GW: That definitely comes across. If you listen to the Melvin Seals’ performances, then you listen to Holly Bowling playing with you guys, a different kind of sound comes in and out that.

Steve: Yeah. Well my thing is—and I would do it in every band as much as possible—I’ll try to get a guitar sound. I thought I could get a guitar sound, which is like the stupidest thing. You don’t get a guitar sound, electric guitar is already a sound. You don’t have to do anything to it. It’s already a sound. [laughter] But I keep trying to figure out how to get a sound. I’ll make the amp like this, or make the guitar like this, or what about this string? I’ll get a pick up, or I’ll get a different pick—it’s just like endless stupidity. When I first started figuring out how to not suck completely, I realized all you have to do really was get a Hammond organ, and a Leslie, and set your guitar up next to the Leslie, and get somebody who could play it, and your guitar sounded great. And I said, “Wow. This is amazing.” I finally noticed that it’s not the guitar sound.

GW: [laughter] Sounds like a lot of self discovery going on here.

Steve: Nobody told me.

Greg: I want to tell a story that I think your readers will enjoy, that really kind of blew my mind. We were out in the barn playing with Zero, with John Cipollina and Steve Kimock the guitar players, and if anybody is familiar with those two guitar players, they’re radically different guitar sounds. We must have been recording or something because Steve and John both had their full setups. John’s setup is Fender amps and Gibson guitars, and Steve plays a lot of Fender guitars, and whatever he used back then, Boogies . . .

Steve: And Cipollina used the really light strings, like the Duane Allman, like 10’s to 38. His bottom string was like a 38. And he played with a whammy bar all the time. I had stupidly heavy strings, like heavier than if I was playing a dobro 14, 18, 28 to 64, like impossibly large strings. My D-string was as big as Cipollina’s E-string. We switched guitars, and we completely switched rigs and . . .

Greg: It was incredible. They just handed each other their guitars and agreed not to touch one control knob of any kind, and just played, and Steve sounded just like Steve [laughter] and John sounded just like John playing through each other’s gear. I guess the sound’s in their hands.

[laughter]

Steve: I guess it’s not like a decision-making kind of thing. It’s more to do with content than the hardware. Yeah, that was pretty frightening. Also—again I think this is trivial—I own all the same equipment, all the same production that’s on that record. I still own the same guitars, same amp, same cable in some cases, from those musical sessions, and I can’t make the sounds that I made on those records.

GW: Back to those conditions playing the moment.

Steve: I can’t even sound like myself, like even the next day.

GW: I guess you’re a different person than you were yesterday.

Steve: Yeah. It’s like some extreme version of “you never step in the same river twice,” or something like that. You really don’t. So there’s no way to—it’s like you can’t go back. That was then, and the decision making, or the touch, you know, as you mentioned, it just changes.

GW: I think a lot of people think we’re solid when we’re really more liquid, we’re ever changing all the time. We’re never the same thing twice. So it’s easy to see as the conditions change, your whole mood, outlook, perception changes, I mean everything is constantly in flux.

Steve: Exactly.

GW: And occasionally you catch these moments of greatness. I really enjoy listening to you guys play. I like music that takes me somewhere, which reminds me, in your early days you guys didn’t even have lyrics. What made you think people were ready back in the eighties for whole albums of just instrumental music?

Steve: It didn’t have to do with that really. I mean, at the level we were working, at that time, the entire idea of having a singer meant we needed a guy with a van and a PA, or something like that . . . We didn’t know a guy with a van and a PA. So . . .

GW: [laughs] So that’s it.

Steve: [laughter] I’m serious.

GW: I believe you. [more laughter]

Steve: People would be saying, “Hey, you need to get a singer.” And we’re like, “No. We don’t have a PA.”

GW: So without a singer, how did Robert Hunter end up joining you guys?

Steve: I don’t think joining is the right word. I don’t know, that’s one for Greg. Also, just a head’s up. I have another interview in sixty seconds. Just thought I’d give you a heads up.

GW: Appreciate that. I guess I’d ask a quick question then about whether you guys were Deadheads back in the day?

Steve: Oh. It was different in that for me because I’ve always adored—from the time I was first introduced to Jerry Garcia’s sound—I always just love his sound. Just adored his playing and his sound and the microtonality of it. The bending and the freedom I heard in it was all very attractive to me. But I also realized, at the time we were doing that stuff, the Dead and Garcia were doing their thing. And as long as they were out there working, we weren’t working. This place, at the Chi Chi Club, there’d be one person there, and next door there would be like ten-thousand people trying to get in to see Garcia. So, it was really rough. I kind of like wanted to distance myself from that trip as a player just so I could have something left of my own, because kind of coincidentally, Jerry and I were into a lot of the same players and a lot of the same influences, had a lot of the same ideas about what a good guitar sound might be. So going forwards, as much as I liked it, I couldn’t go live there without . . . I just couldn’t go live there and be myself. So not really an anti-Deadhead musician, just out of self defense, you know what I’m saying?

GW: Yes, absolutely. You can certainly hear the similarities even though.

Steve: Yeah. But see, the thing is, if you go back, I think those influences show more clearly in the Garcia Band material, the Legion of Mary early on where if you were a guitarist as well and you were familiar with certain musicians, whether it was Roy Buchanan, or like Bloomfield, you hear those people, or B.B. King, or whatever, you would hear those people in his playing, and you’d hear those sounds and you’d go, “Oh, yeah.” You know what I mean? And I think Garcia and I had a lot of the same influences, and when you hear stuff in his playing as well as my playing, part of it was the same influence. And occasionally, I’m sure there’s my stuff in his playing. He had the luxury of being Jerry Garcia, so if he heard something he liked that I did, he could just throw it in there and it didn’t matter. If I put it in there, they’re going to be, “Hey. You’re trying to sound like Jerry Garcia.” Nobody’s going to think Jerry Garcia sounds like Steve Kimock, you know? [laughter] Not that that was stopping me, if there was something I liked, it was fucking borrowed.

GW: [laughs] Well, I’m a big Legion of Mary fan, so . . .

Steve: Oh, me too. Oh my god, I love that band so much. And with Martin Fierro . . .

GW: Well, I don’t want to keep you from talking to other people. I really appreciate getting a chance to chat with you. I’ve been a fan from all the way back.

Steve: Oh shit. I gotta go.

Greg: See ya Steve.

GW: Have a good one. So Greg, do want to finish telling me the story about Robert Hunter coming onboard?

Greg: I met Robert Hunter by playing drums with him. Then I ran into him at a party, and we were hanging out, and he said to me, “I’m a big Zero fan. Actually, most of your fans are musicians.” [laughter] And he says, “You could break out a little more if you had some songs with lyrics.” And I said, “You got any?” And then he says, “Yeah. Got any music?” And I said, “Yeah. We have a bunch of music.” And that was it. We started writing together. We gave him some of our instrumental stuff, and then I started writing with him. We started our little song process where I’d come up with some chord changes and I would play them for him—either make a tape or go to his house and play his piano. I’m a very basic piano player, but he liked my chord changes. So he would write words to them. He would either play guitar and sing himself or he’d work with a pencil and paper and I’d play piano. I’d come up with a basic structure of a song, and then I’d bring it to Steve, and he would add a chorus or a bridge or whatever he added, sometimes melody lines, different stuff. So we had our little three-way song writing team work like that, in that way. Once in awhile Hunter would come out to “The Barn” where we were rehearsing and he would just hang out by the pool table, which we had at “The Barn” and write lyrics while we played.

GW: That’s great, because those are inspirational lyrics there, just kind of feeling the music and having the words pop up.

Greg: Yeah. I was so honored to work with him. The guy is an absolute magician that could just pull words out of thin air. Some of his most well-known lines, “Sometimes the light shines on me. Sometimes I can barely see.” He would come up with lines of that quality in a moment. I would say to him, “You know, this song needs a couple of more lines for the chorus,” and he’d just, “Oh. How about this? Oh, how about that?” And, Bang!

I’ll tell you a quick Robert Hunter story. There’s a Zero song called, “Home on the Range,” with Hunter lyrics and Zero music. We had been playing the song for a few years, and we were in the studio making a studio record, and I said to the band, “Why don’t we play the song upbeat?” Because it was more ballady, “And play it like a rock song.” And the band goes, “Okay. Let’s try that.” So we laid down kind of a rock and roll version of “Home on the Range.” Because it was going a lot quicker, at a faster pace, we ran out of lyrics in the chorus. [laughter] So I called up Hunter at home, and told him what was happening, and I said, “We need a couple more lines for the song.” And he goes, “Okay. I’ll come down and check it out.” We were working at the Record Planet making a record. That’s in Marin County. He says, “Let me hear the track.” So we play him the track. It’s an instrumental track. And he says, “You got a piece of paper?” We give him a piece of paper. He says, “Roll the track again.” And then he writes a four-minute song in four minutes. He says, “Give me an extra track,” and he goes into the vocal booth and he sings a song called “Ermaline”. It’s about a woman named Ermaline. He just does a rough, scratch vocal, and he says, “Fuck that old song. Here’s a new one.” [laughter]

He wrote a four-minute song in four minutes. It’s really good lyrics. “Ermaline, she’s so mean, she gets her cologne from a magazine. She’s so cheap, and that’s a fact, she rubs it on her body and puts it back on the rack.” [laughter] Just a great Hunter lyric. The whole song is good. The lyrics are really good—they're online—anyway, a bunch of good lyrics, and he wrote it that quickly. He just pulled lyrics out of thin air.

GW: When he passed away, I wrote an obituary article for him. It was a hard article to write because there was just so much embodied in that person. There was so much you could say that you could almost go on endlessly. But what it brought around to me personally was that he literally gave me eyes in which to see the world. The metaphorical writing, and the cosmic sense that I got from Jerry’s playing and Hunter’s lyrics, would just open the entire universe to me and gave me a way of looking at the world that I otherwise never would have had. The affect that had on my life, and my life choices, are immeasurable, but I am infinitely grateful.

Greg: You know, his lyrics are closer to music than any other lyricist that I’m aware of. His words are musical. I’m a writer, and he taught me how to write. Are you familiar with my book Face the Music?

GW: I knew that you did one but I haven’t read it.

Greg: It’s a novel about a guitar player. I’m just finishing up the sequel. He (Robert) read for me, and line edited a very early version of the book, and basically taught me how to write. And now I’m at a place in my life where I enjoy writing about going to a gig as much, if not more, than going to a gig. [laughter] You know, just sitting home, working by myself. I really enjoy the solitude of writing. I imagine you do a lot of writing yourself.

GW: I’ve never published, but I’ve written three novels.

Greg: Oh yeah?

GW: I just like the writing. I don’t like the, “Look at me,” sales part, so I just never go that route. I’m not a “look at me” kind of guy.

Greg: If you get a chance, you can get my book anywhere.

GW: I’ll do that for sure.

Greg: It’s a quick read. It’s all about stuff you’re familiar with, gigs and bands and music, and musicians. I’ll tell you what the book’s about. I read an article in the New York Times about prodigy musicians who start playing at a very young age. It was mostly about classical musicians, but it was about all musicians. It said, for example, to get a gig as first violin in a major symphony orchestra you have to be so good that virtually no one gets those gigs that didn’t start playing when they were four-years-old or six-years-old, and they’re practicing, practicing, practicing tens of thousands of hours. While all those kids are home practicing, all the other kids are in the sandbox learning social skills. So when they grow up, a musician that’s that good never had a chance to learn social skills, like how to talk to their girlfriend or their landlord or anything like that, but they can communicate through their instrument. And that’s how they communicate. So that’s kind of what the book’s about.

GW: Interesting.

Greg: About a guitar player.

GW: An awkward guitar player.

Greg: [laughs] Yeah.

GW: I have to ask because you were talking about how good it is. I was talking to a friend of mine who’s always talking about how he could never be as good as that guy, or some other guy even though he’s a really good guitar player. Yet so many people like his sound that he’s really popular. So I was contending the question of talent over what your personal sound is. You don’t always have to be the most structurally best guitar player in the world if people love the sound you put out.

Greg: Yeah. That’s a good point. To me, Kimock’s got one of the best guitar sounds in the country. He spends a lot of time working to get that sound. And if you ever say to Steve, “Oh, you’re a natural talent, a natural talented musician.” That’ll piss him off. [laughter] He says, “No, man. It’s work. Hard work.” And he has put in the work to do what he does. One of the main reasons I play in Zero is just to listen to the guitar playing because it’s so good.

GW: He’s beautiful, and his light touch is just amazing to me. It’s really phenomenal. I have a question since you’re talking about music in this way. What is it about music that can drive somebody so much for Kimock to put in that many hours? What is it about music that grabs people to drive them to practice that much?

Greg: Yeah. That’s a really good question. I play the drums for hours and hours and hours. I like playing the drums. It’s really fun to play the drums. Ask any young kid, sit him on a drum set, it’s just so much fun to bang on all that stuff. I think it’s the most purely expressive art, music is. It’s an expression of pure motion. I think motion is like maybe the one thing that everybody agrees on. Music is just a pure expression of motion.

There’s a little scene in my book where the guy’s talking about if you took two chairs and you put one chair on the most idyllic beach in Hawaii at sunset, and you put another chair next to a dumpster that smells like piss with a bunch of broken glass around, and put everybody in the world in both chairs, and then say, “Which place do you like better?” Well of course most people would say that nice beach. But there’d be some people that had a kid drowned on a beach or somebody that found a hundred-dollar bill beside a dumpster that saved their ass. You could think of stories, or circumstances, as to why one person would like one chair over the other. It just shows that there’s no real objective truth except, I think—I just kind of came up with this theory—except motion. You know, motion of breathing, of your heartbeat, of planets orbiting, plants growing and everything moving, your blood flowing, rivers flowing, and everything’s flowing. I think that everybody would agree that that’s a positive thing, that motion is. So what’s the most pure expression of motion? Music. I don’t know if that answers your question. [laughter}

GW: It certainly intrigues me. Objective truth is hard to see with a subjective mind. It would take an objective mind, or at least one entrenched in the moment of things, to see further into what you’re saying. I see the world as fluid, not solid, so I definitely understand where you’re coming from. I like the picture you described though it will require more thought on my part to go deeper. I can see where connecting with motion in that way, be it musically or not, would be captivating to many.

Greg: Uh huh.

GW: So, you guys are going to be doing a few shows at the end of July. Now that you’ve got this album out are you going to be doing any other follow up stuff with Zero live shows?

Greg: Yeah. We have a whole bunch of shows in the Northeast in October that have not been announced. They’re confirmed. They’ll be announced soon. And we’re looking at a bunch of other stuff. I think there’s some stuff in December. So yeah. We’re looking to do some more playing. We got a new keyboard player/singer named Spencer Burrows, who’s just a fabulous musician. It’s a lot of fun playing with him.

GW: Great to hear. Looking forward to it. I’m curious, are you still a practicing lawyer at this point?

Greg: Not very much, but some. I do pot stuff.

GW: All the legal stuff issues, or the illegal stuff issues?

Greg: [laughter] Yeah. I’m a pot advocate. I think it’s a positive thing. I think if pot were allowed to proliferate the way it naturally does, which grows in practically any climate, just grows wild, it would be a better world. I think it would be in food, building materials, nutritional materials and stuff. I think everybody would at least get trace amounts of THC by just handling it and that would make for a better world. I think it would be a more peaceful world if the whole species ingested at least trace amounts of psychedelic drugs. I don’t think anybody is going to take a psychedelic drug and sit on a beach in Santa Barbara and go, “That’s a good place for an oil well.” [laughter] It gives you a different kind of perspective. It’s a positive thing.

GW: Yeah. [chuckles]

Greg: I’ve done what I can to make it legal. I had kind of a landmark case I did in federal court in 2015. I represent the first licensed marijuana dispensary in California that opened in 1997. It’s still illegal under federal law today. I got a court order in 2015 in front of a federal judge that said my client can distribute medical marijuana in California free of federal interference. And because of that case, things busted open in California to legalize it in 2016. So I worked really hard on that for several years. That turned out good, but it’s still illegal under federal law, and that’s still a hassle for people. The banking part is a giant hassle. They’ll still bust people, and there’s still a lot of people in prison. It’s just ridiculous in my opinion.

GW: It would probably do us better than alcohol, coffee and meth. [laughter] We do need to calm down a little bit.

Greg: Yeah.

GW: I sure appreciate you giving us your time, and your music. I’m glad you guys are keeping it going, that’s for sure. Thanks for joining us today.

Greg: I really enjoyed talking with you. This has been great. Your support of the music is just wonderful. Thank you so much. All right, brother. Be well.

“We will not speak, but stand inside the rain, and listen to the thunder shout, I am.”