Article Contributed by Gratefulweb

Published on November 15, 2025

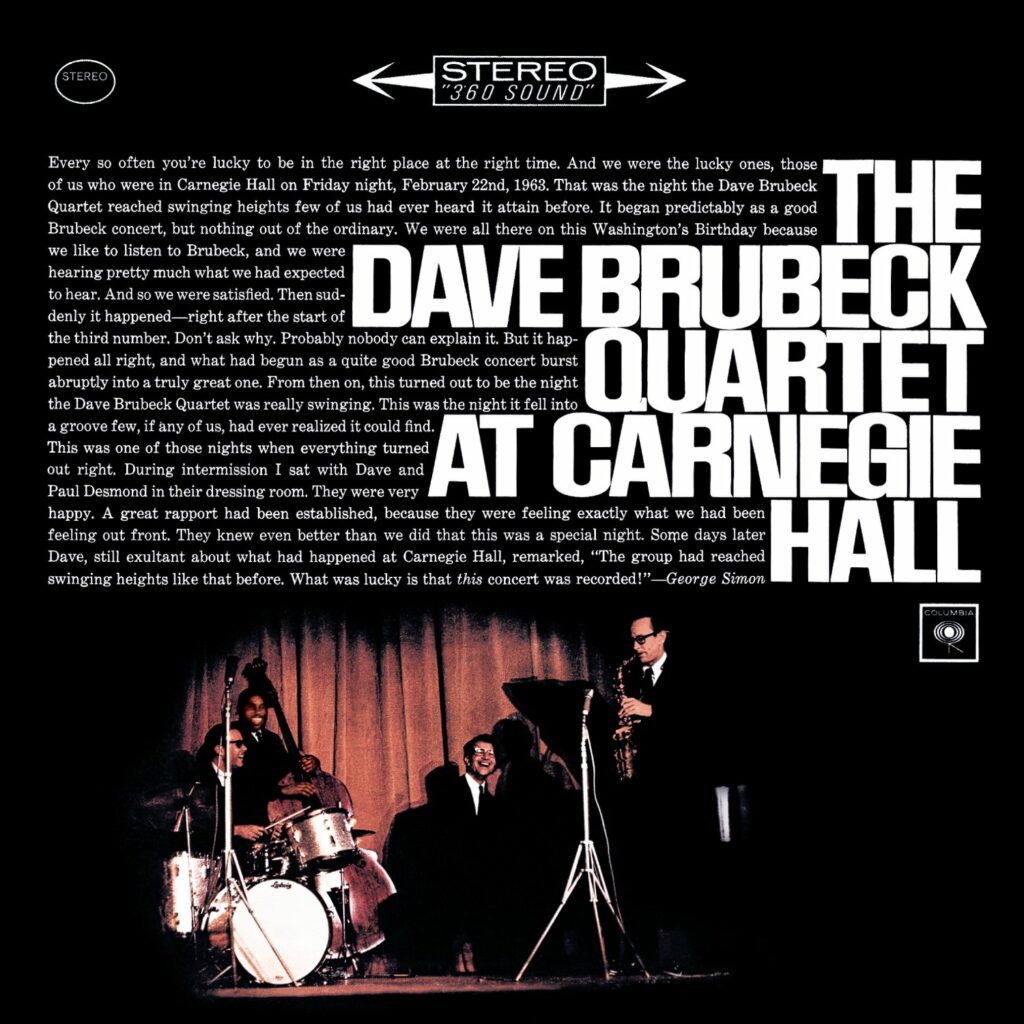

Dave Brubeck Live At Carnegie Hall

Some albums age. Some mellow. A rare few ignite — immediately, relentlessly, and forever.

Dave Brubeck’s At Carnegie Hall, recorded February 21, 1963 and released the same year, remains one of those impossible recordings that refuses to quiet down with time. Sixty-plus years on, it still hits with the same shock of recognition: this is what live music can be when a band is tuned not just to each other, but to something larger moving through the room.

The brilliance of this album isn’t nostalgia, or era, or myth. It’s the electric presence of four musicians at the absolute apex of their powers, meeting the acoustics of a legendary hall and pushing themselves past even their own expectations.

From the opening blasts of “St. Louis Blues,” the quartet sounds startlingly alive — not warmed up, not easing in, but already mid-stride, mid-flight. There’s an urgency to the playing, a kind of high-wire confidence that only comes from years of trust and intuition.

Desmond doesn’t just solo; he levitates. His tone is the definition of cool clarity — warm in the center, glass-smooth at the edges, with melodic lines that seem to pour effortlessly out of him. On “For All We Know,” he shapes phrases with such grace that the silence between them becomes part of the music itself, each breath a small act of intention. It’s a masterclass in restraint and lyricism — Desmond letting the melody unfold like light through a half-opened window.

“Castilian Drums” is the moment many listeners return to again and again, partially because it’s impossible to believe one human can conjure that amount of rhythm, color, and architecture from a drum kit. Morello manipulates time like a sculptor — stretching, compressing, teasing, exploding — while never losing the internal pulse. His solo is not a spectacle; it’s a narrative.

Wright’s bass doesn’t shout — it anchors. His tone on this night is so rich and grounded that it creates the center of gravity for the entire performance. Every rhythmic risk the group takes is possible because Wright makes the floor feel solid.

Brubeck’s playing at Carnegie Hall is bold, architectural, and full of kinetic energy. His left-hand power — those striking, percussive chords — gives the band its forward momentum. His right hand dances and declares in equal measure. You can hear him listening as deeply as he is playing, steering the quartet through every swell and shift.

There’s a reason this recording feels almost three-dimensional.

Carnegie Hall amplifies nuance. It expands space. It adds a physical glow around every note.

On this album:

It’s as if the room itself is performing.

Most records become familiar.

This one becomes deeper.

The more you listen, the more layers reveal themselves — hidden rhythmic pivots, sly phrasing choices, harmonic curveballs that didn’t register the first dozen times. It rewards obsessive listening the way great improvisational music does: every pass reveals a new corridor, a new spark, a new detail you swear wasn’t there before.

For anyone who knows what it feels like to be carried by a band when everything locks into place — when time stretches, when breath synchronizes, when your whole body feels the music rising — Carnegie Hall scratches that same cosmic itch. Quietly. Gracefully. Without needing to announce it.

At Carnegie Hall is more than a concert recording.

It’s an energy field — a moment where skill, intuition, and inspiration collided in front of microphones that happened to be rolling.

It’s the rare kind of album that:

Because this isn’t just a great jazz record.

It’s a reminder of what can happen when musicians trust each other completely, when the room leans in, when the music starts playing them instead of the other way around.

A live album that still feels alive.

Still feels dangerous.

Still feels like fire meeting air.

Still feels like the moment everything changes — every single time you press play.