Article Contributed by Sam A. Marshall

Published on 2023-08-15

When I was back there in ‘seminary school’ in the late ‘60s – actually a third-rate parochial school in Cincinnati but definitely the same kind of spineless swine and cemented minds running the joint, I began seeking my mental oasis in the psychedelic and progressive rock of ‘underground’ FM radio. (My lifelong fascination, as readers of my regular features here know by now.) But for starters, when I was still an ‘uninitiated’ 8th grader in 1968, AM radio was all I knew at first. We all had to start somewhere.

Amid the steady stream of the early ‘psychedelic’ bands of Top 40 radio in the 1967-68 period – think Jimi, Cream, Doors and Steppenwolf – The Moody Blues had an enticingly different sound. My gateway Moody’s song was the single “Tuesday Afternoon” – from the band’s groundbreaking 1967 concept album, Days of Future Passed. And for me, this magical single – all 2:16 minutes of it! – had a different kind of psychedelic hook: It was acoustic-based, with quasi-trippy lyrics, plaintive lead vocals and harmonies, and orchestral textures, courtesy of that mysterious tape-playback instrument, the Mellotron! To say the least, I didn’t know it at that time – or even what a ‘concept album’ was, but I was already ripe for a band like The Moody Blues. For me, they arrived right on time!

From the vantage point of nearly 60 years on – a lifetime, in fact – Days of Future Passed stands as a turning point in rock music history. Combining an orchestra with a rock group throughout the album, having Mellotron as a full band instrument, flute, cello, and key moments of poetic recitations – the finished piece may very well have been the ‘starting gun’ for what soon turned into the prog rock race of the late ’60s and early ‘70s. Unless, of course, you started your race with The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Or if you didn’t fall into prog and concept albums yourself until a bit later with Procol Harum, The Nice, Pink Floyd or Yes.

Now, in 2023, the Moodies’ bassist/vocalist/songwriter John Lodge – proudly wearing his prog credentials on his sleeve – has returned to his band’s early masterpiece with an emotionally stunning, updated version for the new century, titled Days of Future Passed – My Sojourn.

In a recent phone conversation with Grateful Web, Lodge explained that the musical concept behind the original Days album – blending classical-style music with pop-rock songs – did not originate with the band’s members. The group, which formed in 1964, had had a change of line-up between its five-man debut album in 1965 and their next album in 1967. Newcomers Lodge and guitarist/vocalist Justin Hayward had joined in 1966, but the band needed time to sort things out for themselves. Still going through a commercial and financial trough at the time, the five-member band were eager to do anything that might help them break through into the pop mainstream. Little did they know, a big opportunity was just around the next corner.

“I don’t know why they chose us!” Lodge said, laughing about the unlikeliness of the Moodies getting this obviously prestigious assignment. “Actually, we thought perhaps it was because we were the cheapest band under contract with the label!”

As he told it, Decca Records – also once the home of The Rolling Stones – was launching a new specialty label in 1967 titled Deram Records. As the story goes, the company wanted to have a special release with that unique classical-pop hybrid, he explained, as a way to demonstrate their new stereo imaging technology. The company even gave its recording innovation a special name – Deramatics, which, if you think about it, almost sounds like a band name in itself. But the Moodies held on to their name, in any case, and – over their 50-plus-year career – went on to sell more than 70 million albums worldwide.

At first, the company’s brainstorm was to have the Moodies do a pop adaptation of an Antonín Dvořák symphony, but the band held out for having their own songs recorded with orchestral atmospheres and intervals. And the narrative concept was theirs, too – a day in the life of the average person, set to music.

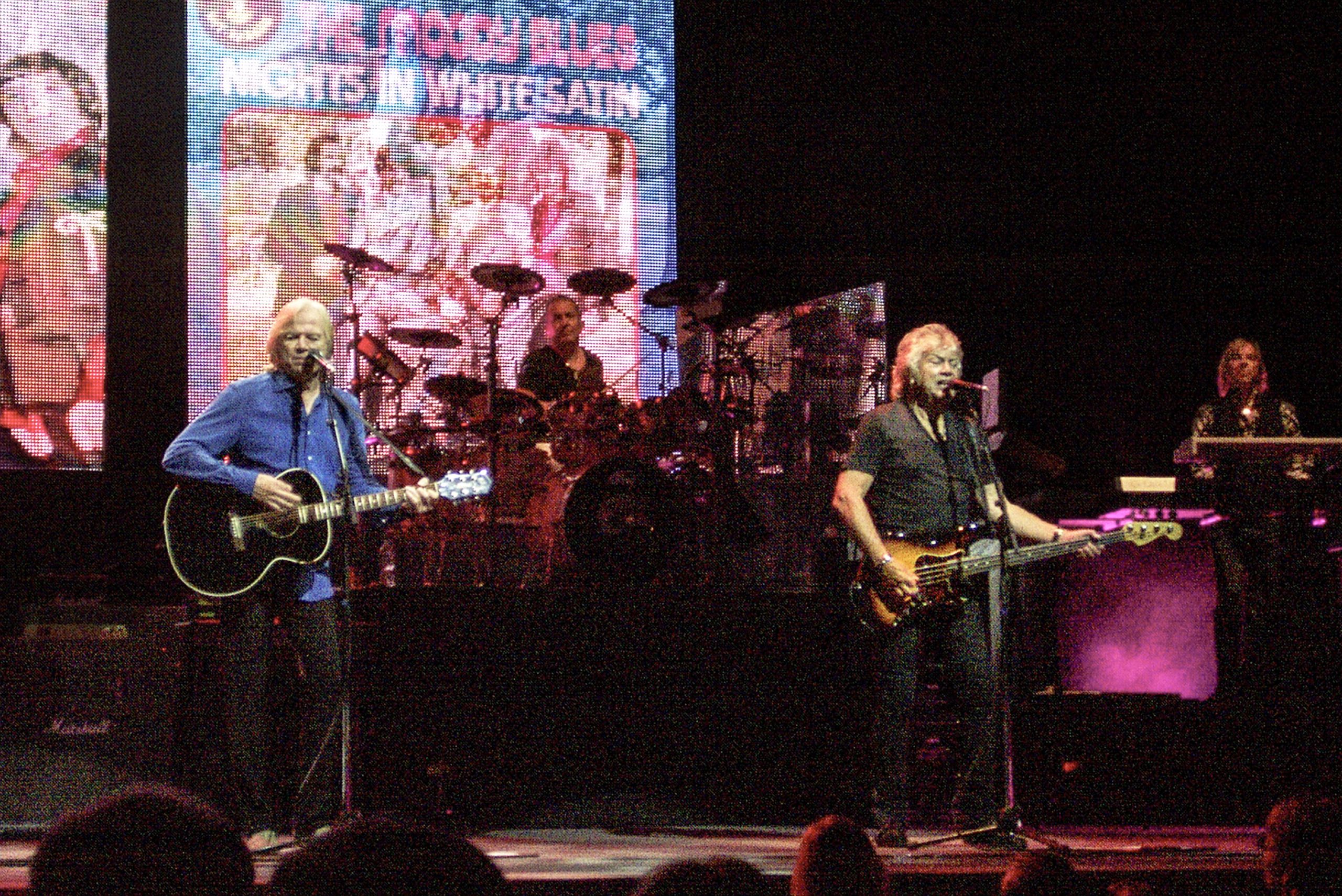

In the long view of musical history, DoFP is not merely notable alone for that hit song, “Tuesday Afternoon” or for making the concept record more of a must-have household object. It actually became more renowned for its timeless song of love and loss, “Nights in White Satin”, which was actually the first single from Days, in late 1967. With its sweeping, orchestral passages, and its spoken-word companion piece titled “Late Lament” – penned by drummer Graeme Edge and then recited by keyboardist Mike Pinder – it became more of an in-demand FM radio song.

As more people learned of the atypical rock track, it began to drive increased sales of the album. Then “Nights” was re-released as a single in 1972 and scored a much wider audience the second time around. It has featured prominently as a finale or encore in most of the Moodies’ live performances, especially those in tandem with live orchestras in the band’s latter years. Their special 1992 recorded performance with the Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Live at Red Rocks, turned that song, most of all, into a must-hear production for the ages.

Which brings us back to the present day, a time in which the Moody Blues exist as a band mostly in memory and recordings, though some surviving members are still musically creative. (The members last performed as a band in 2018, at their long-petitioned induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Also, former vocalist/flautist Ray Thomas passed away in January 2018, at age 76. And drummer Graeme Edge left us more recently, in late 2021, at age 80. Lodge himself is now 78.)

The time, indeed, seems right for this music to be revisited and reinterpreted for the present day. Lodge brings a well-traveled voice and some notable variations to his own pieces on the album, and special guest vocalist Jon Davison of Yes stands in sweetly on the Justin Hayward vocal moments. So, if you’re like this writer and know the original well, you will hear much that is deeply familiar, yet with newer emotional resonances. And if you lean more into progressive and concept rock than the average music fan but still haven’t discovered this early Moodies’ masterpiece, then Lodge’s lovingly performed new version is an excellent starting point for a new musical adventure.

In the following condensed interview with Grateful Web, long-distance voyager Lodge shared his thoughts on the legacies of the Moody Blues and of the Days of Future Passed, his journey to now and how the idea for My Sojourn came to life.

GW: Great to talk with you, Mr. Lodge. I feel very honored. And may I call you John?

Lodge: Yes, certainly.

GW: Thank you. So I’ve been listening to and enjoying your new version of DoFP. I’ve got a batch of interrelated questions for you about it. Hoping to cover as many as we can in a short time.

Lodge: Of course.

GW: Briefly, some personal history: I was 14 in 1968 when I heard “Tuesday Afternoon” the first time, and soon after that, the full album, Days of Future Passed. And also, the Moodies were the very first arena act I saw, in 1970. It’s so interesting to hear the new version now, from this latter-day point of view. It has that sepia-toned perspective of a life lived, versus anticipation of the future. And Graeme’s [MBs drummer Graeme Edge] voice [on the poetic sections] seems more like ‘Father Time’ than [keyboardist/vocalist] Mike Pinder on the original. That, too, seems more emotional, more perfect to me. How much of this perspective change were you conscious of when you chose to update the album and how much of it is just serendipity?

Lodge: I think the [original album] captured that feeling of the late 1960s, in the world, but it’s also relevant today. That’s why I wanted to go on the road first of all and perform it live [in recent years, with his own band]. And the reaction was so good, I [decided] that I really wanted to make [a new version of] the album. I realized there was this huge leap-frog [of time] from the late ‘60s to now, and – heh – I asked myself, “What’s taken me so long?”

It’s why I called it Days of Future Passed – My Sojourn. I’m the same person, I’m the same me. And it’s the same Graeme [on the new recitations]. But we’ve all been living our lives. I wanted to really state that, y’know? So [the new version] does take a look back. Not reminiscing, but saying, “OK, that’s what we did in 1967.” And I recorded it now because the themes [the passage of time] are more timely now, and the lyrics seem to be pertaining to my life. It’s my sojourn. It’s a reflection, I think, of me and the Moody Blues, and of our fans [over time].

GW: No doubt that there’s a lot of shared history between the band and your fans. But also, are you finding that you’ve been attracting a lot of new listeners?

Lodge: Definitely. We’ve been seeing lots of younger people at our shows, which is fantastic. The thing is, it [sounds much different] now, too. When we first recorded DoFP in 1967, we were using only two four-track tape machines, and it was the first [true] stereo album to be released. I realized that with today’s technology, I could – hopefully – create that same kind of vibe [as the original] but with a much greater, more dynamic audio spectrum. All of us – the band, the engineers, and myself – definitely think that we have.

GW: I’ve been listening to the two recordings side by side, to ‘refresh’ my synapses a bit. My perception is that because you now have so much experience as a stage performer, the dynamics [on such songs as “Peak Hour”] have a much greater sense of drama, more of a live rock sound and energy. More bottom end and power chords. So – less pastoral, more arena!

Lodge: I think you’re right. When [the MBs] made the [1981] album Long Distance Voyager, and also the earlier [1972] album Seventh Sojourn, we made those after being on the road for such a long time. I think we brought in a lot of extra energy into the recording. I was hoping to do the same thing with this [new recording of DoFP]. The original Days album was written, rehearsed and recorded in a studio. [After performing it completely live], my intent [with the new recording] was to capture DoFP in a different light.

GW: I’d like to go back in time, just for a moment. You’ve pointed out in other interviews that everyone in the Moodies – including yourself – was inspired and heavily influenced by the rock ’n’ roll pioneers and pop music of the time. Since the record company (Decca/Deram) first came to you with the idea of the orchestral hybrid album, what do you think they saw and heard in the Moodies’ sound that inspired them to offer you that project?

Lodge: Now – heh – you’ve lost me. . . No one has ever asked me that question! I don’t know why they chose us!

GW: Really?

Lodge: I really have no idea what inspired the record company to invite us to work on this. Because, we actually had gone into the studio and made four or five demo recordings, and sent them to the record company. Maybe someone listened to them and thought, “Ahhh, this could work.” But then, they approached us with this idea [to combine classical and pop music], and we said “Yes.” Actually, we thought perhaps it was because we were the cheapest band under contract with the label! Or, perhaps it was something about our sound – four guys singing harmonies, the flute, the Mellotron. We had all the ingredients of being something different, and we were writing all of our own songs at time. It could have all contributed to the company deciding, “Let’s give it to the Moody Blues.”

GW: That’s great! I’ve read that you and the band worked round the clock for a week when recording DoFP. Could you please tell us a bit of what it was like working on the project with that intensity? The give and take with the conductor and the orchestra when you got to that stage, the interactions among yourselves and your producer?

Lodge: Y’know, at the time, studios [followed a format] of three recording sessions a day. Like 10:00 to 1:00, 2:00 to 5:00 and 6:00 ’til 10:00. You used to book your sessions, and when they were over you had to leave the studio or wait for the engineers to come back. We knew that if we wanted to make something different, we wanted 24-hour “lockout” [exclusive usage]. We went to the chairman of the company and said we’d like a “lockout”. And I don’t think they had ever had a request for that before, but, fortunately, they agreed. And it was wonderful, because we were recording a tune a day, and as the evening came we’d relax for a while. Midnight would come and then we’d start again. As the early hours came – 2:00, 3:00, 4:00 in the morning, we realized that was a great time to be constructive and creative. It was great to be able to do that.

GW: Very interesting! So, comparing your new recording to the original project, would you say it took you less time [to record again] because you knew and had lived with the material for so long? Or did you and your band [10,000 Light Years Band] and team have to go back and re-study it and come up to speed on it?

Lodge: We really started from scratch again, really. Obviously, we listened [a lot] to the original album. And we recorded it a lot differently. We recorded some parts and took them to different places, back to home studios, [other cities] and so on. My stage manager has a studio of his own where I recorded all of my vocals, for example. That worked really well. My keyboardist Alan Hewitt is my musical director. He had put all of the basic idea together [from his keyboard parts], and then he’d come to me and I’d put my bass parts on it. And then we brought in my drummer [Billy Ashbaugh] and we put the drum parts on. Then we’d listen to it, and I’d say, “Ohhh, that’s not right.”, or, “This is great!” Or. . .“Make adjustments.” So that’s how we built the tracks up from the bottom, going backward and forwards. We’d send the files to my cellist [Jason Charboneau] up in Detroit, and he’d work out the orchestrations. Then, we’d send the files to my guitarist [Duffy King], also in Detroit. And then it would all come back to me. I’d listen to it all and say “Yes,” or “No.” It took about a year with us changing things to get it all right. Then, I absolutely loved it, to be honest. In fact, if I didn’t absolutely love it, I wouldn’t have released it. I think it stands up completely on its own.

GW: Because you worked so quickly back in 1967, it seems that you maybe already had all of your pieces written. Was that the case or did you do any composition or completion of structures in the studio, because you had all that time?

Lodge: We did do a bit of writing in the studio, but a large part was already written and rehearsed. The first time we recorded “Nights in White Satin” was for BBC Radio in England. But we rehearsed all of the [lyrical] songs before we recorded them. And, when we were recording, we’d make adjustments. It was a great time [with all the teamwork]. We’d listen to something the day after we recorded it and just by [letting it sit overnight], we’d hear it again and think, “Umm, we should change that. I’ve got a better idea for that.”

At that time, because we were only in the studio for a week, we were always fine-tuning. But, of course, there were also limitations. We were only using four-track machines, and you had to commit yourself to the part. Once committed, it was there forever. You’d take [one group of two-track mixes and combine on the second machine, and so on]. And we’d keep combining them. It was quite a complicated process!

GW: There are other bands who had worked with orchestras early in their careers and had mixed results, because orchestras then weren’t used to rock musicians and the bands didn’t necessarily have technical skills of working with conductors orchestras. But the Moodies’ end product seemed fairly seamless, even with some synching problems that are now eliminated [in remixed versions]. Major musical themes [melodies from the lyrical songs] are alluded to in the early musical motifs and woven through the piece. Did any of the MB band members have classical training esp. in musical notation, or did the band have an arranger helping to translate their songs to the orchestra?

Lodge: We were very fortunate. We met a guy named Peter Knight. He came to see us at a pub in London and heard what we were doing. We talked and he said he knew what we should be doing. When we were recording, we’d [give him] our rough mixes that night, and then he’d adapt the orchestrations or re-arrange something to what we had recorded the day before. He was a fantastic guy. He worked well with us and our producer, Tony Clarke. [Knight] was so good that Justin and I used him again on our Blue Jays album. (A 1975 Hayward-Lodge duo album during the MB’s early ‘70s hiatus.)

GW: Could you talk about when and how you first conceived of doing this new version, and did you talk about it with Graeme right away? Or was that only after you worked with it and got it pretty solid?

Lodge: Just after the Covid period, I had recorded and released a couple of singles [with the 10,000 Light Years Band], and I started thinking about what I wanted to do on the road, y’know. I thought it would be good to actually do DoFP, and I started thinking about [how to do it].

I got in touch with my keyboard guy Alan [Hewitt] and asked him about it. He said we could do the music easily. “No problem,” he said. But he also said we’d need a “defining moment,” something that [would be a focal point] to build the [stage] show around. So [in later 2021] I went to see Graeme [to explore the idea]. Y’know, he and I first met when he was 16 and he was playing with another band. I used to see him every Saturday afternoon. It was strange that four years later we started working together. And we lived our lives together. All that time.

So I visited him and said, “Graeme, I’m thinking about doing DoFP on stage. What do you think? I really would like you to record your poetry, so you’ll always have a place on stage with me.” And he said, “John, I’d love to. Keep the Moody Blues’ music alive!” And I said, “OK!” So, once I got Graeme to say “Yes,” I knew I was on the right track, because Graeme had never recorded his poetry before [previous recitations of his poetic pieces on record were done by MB keyboardist Mike Pinder]. And it’s such a piece of rock ’n’ roll history, though. But I told him, “Graeme – Not only am I going to record you, I’m going to film you, so you’ll always be on stage with me!”

Unfortunately, I was only with him just a few days before he passed away [November 2021], so he never saw himself on stage. But his family did, and I’m really pleased about that. And then, we had Jon Davison [current lead vocalist of Yes] join us once for an encore of “Ride My Seesaw” and asked him afterward if he’d like to be part of [making] this album. And he said he’d love to. So all the parts were in place, and I knew we could really do it. And so we started recording.

GW: Well, I’ve got just a couple more questions, John. I know you perform in different sizes of venues, both theaters and clubs. So what is your band configuration for this tour and how often do you get to play with an orchestra?

Lodge: It’s kinda complicated, especially with the parts where we have to [synch] in Graeme’s parts. We’ve actually done only one show with an orchestra, and that was in Palm Springs. But I’d like to do more shows with an orchestra. My keyboardist Alan [Hewitt] is a master of keyboard technology. I don’t know how he does it. He’s brilliant! And he seems to cover everything that the orchestra would do.

My cellist Jason – his cello is my main instrument in my band – has got a load of foot pedals that [give him many tonal and dynamic options]. So he covers a huge area of the bass frequencies in the orchestra [sounds]. And my guitarist Duffy also uses pedals that emulate many [textures]. I know it sounds strange, but we kind of “tempt the audience” into hearing certain sounds, and they can actually hear the whole sound. They’re not hearing an orchestra, but we [suggest the full effect].

GW: So you’re supplying some of the sounds with MIDI’ed parts but also leaving space in the music for the listener’s imagination to take over and fill in the rest?

Lodge: Yes, and we do it differently on stage, too. On the original DoFP, it was all one go. Everything flowed together. But it’s really important to have gaps between the songs on stage. Alan needs to [switch around] between songs, and the gaps give him a chance to [make those transitions].

GW: What kind of influence do you personally see that the Moody Blues and DoFP had on what became known as progressive rock and the artists who did concept albums?

Lodge: I wouldn’t say that we had that much influence, really. The way I see it, it seems it was more like that was something that was just “in the air” at the time. I really don’t think about it. I enjoyed all these other bands – like Genesis, Yes and King Crimson and hearing what they were doing. I remember [certain ones] had come to us at Threshold [the MBs own label from 1969 to early 2000s], looking into joining our label.

And we used a lot of different technology. We had one of the first Moogs [synthesizer] that took up a whole wall, 6 x 10 feet, and we first used it on “Melancholy Man” [a 1970 song from Question of Balance, before Emerson, Lake and Palmer]. And after the Mellotron, we also used a Chamberlin [another pre-recorded tape playback instrument] and DX7s [later Yamaha electronic keyboards]. We tried everything and if we could use it in our sound, then we’d add it. But we didn’t just use it because it was there.

GW: Your recent 2023 summer North American [solo] tour was very compact, just a couple of weeks. Could you talk about your plans about any more legs in North America or Europe?

Lodge: Yeah. I do want to come back to America, to [the coasts] and the Midwest, too. Everywhere, y’know? I’m so proud of DoFP, I want to share it with everyone. And my band loves playing it. That’s the main thing. I think next spring we’ll be back on the road. Next year in Miami, we’re going to be doing the Flower Power Cruise [March 21-28, 2024, managed by Royal Caribbean Group]. I think the promoters are looking closely at [next steps] with my agent.

GW: I imagine a lot of it would have to do with the availability of your band members who might have other commitments, right?

Lodge: Well, it’s really great, because they’re very committed to what we’re doing. I like to give everyone the long plan. I want to be touring [at least] through March of next year. So they’re going to hold that position open for me.

GW: So, naturally, because I live in Cincinnati, I’m curious whether your plans would include coming here.

Lodge: I’d love to!

GW: That would be great! Really looking forward to hearing DoFP live sometime. Thanks again, John, for squeezing us into your busy schedule and for taking on this project. The dynamics in the new recording are great. It’s a great headphones album!

Lodge: Thank you very much, indeed. I appreciate that.

For more information about John Lodge, the “Days of Future Passed” album and future tour dates, please visit the artist’s website at: https://johnlodge.com.