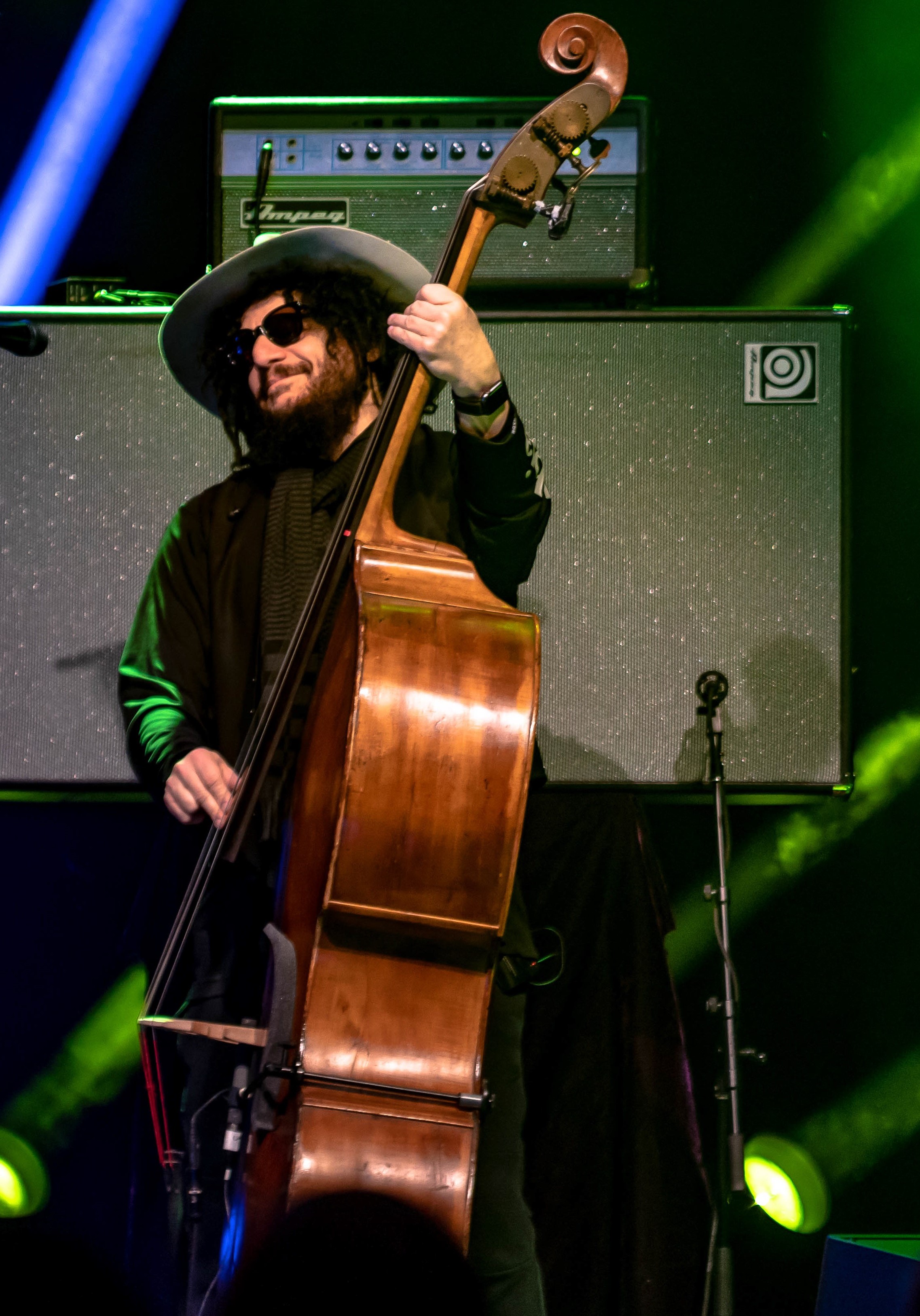

Don Was – the veteran, multi-Grammy-winning musician/producer and current president of Blue Note Records – is one of those virtual Renaissance men who always seems to have many pots a stirring. Over time, he has been a bassist, record producer, music director, film composer, documentary film maker and radio host. And 2024 promises to be no less busy for him.

At the helm of that pioneering American jazz music record label since 2012 and coming off extended touring with Bob Weir & Wolf Bros, as well as recent Sirius XM and National Public Radio shows, this man of perpetual motion has new touring and business ventures on the horizon. And, just now – in early April 2024 – he carved out a small notch of time to talk with us here at Grateful Web about what’s next on his schedule.

Tops on Was’ list is the launching of the new photo exhibition of jazz music history, “The All Seeing Eye: Blue Note Records Through the Lens of Francis Wolff,” opening at Boston’s Boch Center on May 1, 2024. (He will also help to kick off the exhibition with a special, by-invitation-only pre-opening there on April 19.)

The Boch Center is the home of the exhibition’s main sponsor, The Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame (FARHOF), which opened in 2019 within the Center’s Wang Theatre. And, even with a six-year hiatus from 1979 to 1985, Blue Note Records stands as America’s longest-running jazz music label, in no small part due to Was’ tireless, latter-day contributions. As you’ll see, Was tells us more about how he merged forces between those two organizations for this special exhibition.

In 1940, Francis Wolff – whose photographic images of Blue Note recording artists lent their distinctive graphic impact to hundreds of the label’s album covers through the late 1960s – became co-partner in the jazz music company, which his friend Alfred Lion had just founded in 1939. Both men had been recently-arrived U.S. immigrants who had fled the Nazi regime in Germany to seek safe haven here in the late 1930s. And both were avid fans of jazz who had landed right in the thick of that scene in New York City.

It seemed like the right time and place for their record label. Fascinated as they had been by the explosive creative energy of the American jazz/blues musicians at the time, Lion and Wolff dedicated themselves to creating a home for all of these artists to record and to perfect their craft. At the same time, the record company helped to make the work of these musical pioneers available to a wider base in the growing jazz music market.

Blue Note immediately began with recording and releasing the work of such boogie woogie piano artists as Albert Ammons and Meade Lux Lewis, and in time they would expand into more proper modern and avant-garde jazz, with such artists as Art Blakey, Joe Henderson, Horace Silver, Ornate Coleman, Miles Davis, Dexter Gordon, Herbie Hancock, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy and Thelonious Monk, among many others.

And for Wolff, who had also been a commercial photographer in Berlin, Germany prior to his arrival in the U.S., the album cover format also gave him a natural canvas on which to craft his personal photographic vision. Reid Miles – the Blue Note album designer who joined on in the mid-1950s – often used Wolff’s images in stark, dramatic ways that expressed the combustible chemistry of the music in the vinyl grooves within. So this exhibition – built around Wolff’s intimate and revealing images of so many legendary jazz musicians in both the studio and in performance – makes a strong case for both the historic and artistic importance of his body of work.

Having had his own jazz “Road to Damascus” moment in 1966 when he heard saxophonist Joe Henderson for the first time on a car radio while waiting for his mother, Was got jazz-tuned right then – at age 14 – and has remained a serious, lifelong fan. Truly, Blue Note was in Was’ DNA from that moment forward. Signing on new artists at first during a brief stint as the same music labels’s CEO and creative director in 2011, Was then took on the reins as Blue Note president in 2012 and began taking a more active role in steering the then-73-year-old company in the new century.

Was’ mission at Blue Note has been not only to help in preserving the label’s legacy for future generations but also to continue its pursuit of excellence with new jazz artists and recordings, and to help keep jazz relevant among newer generations of listeners. For example, Was has not only been a champion for such contemporary artists as Robert Glasper and Norah Jones but also was instrumental in the latter-day re-signing of saxophone legend and former Blue Note artist, Wayne Shorter. (Shorter — the late, great Miles David and Weather Report collaborator and band leader who passed away in 2023 — released his final, three-disc album, Emanon, on Blue Note in 2018.)

In this following interview with Was – the acclaimed producer of and collaborator with such music artists as Bonnie Raitt, Bob Dylan, Ringo Starr, John Mayer, Willie Nelson, Brian Wilson, Roy Orbison, the Rolling Stones and Bob Weir – you’ll learn essential history about Francis Wolff and Blue Note, and how the exhibition came together. In addition, he shares more about his personal passion for jazz and his own history with Blue Note.

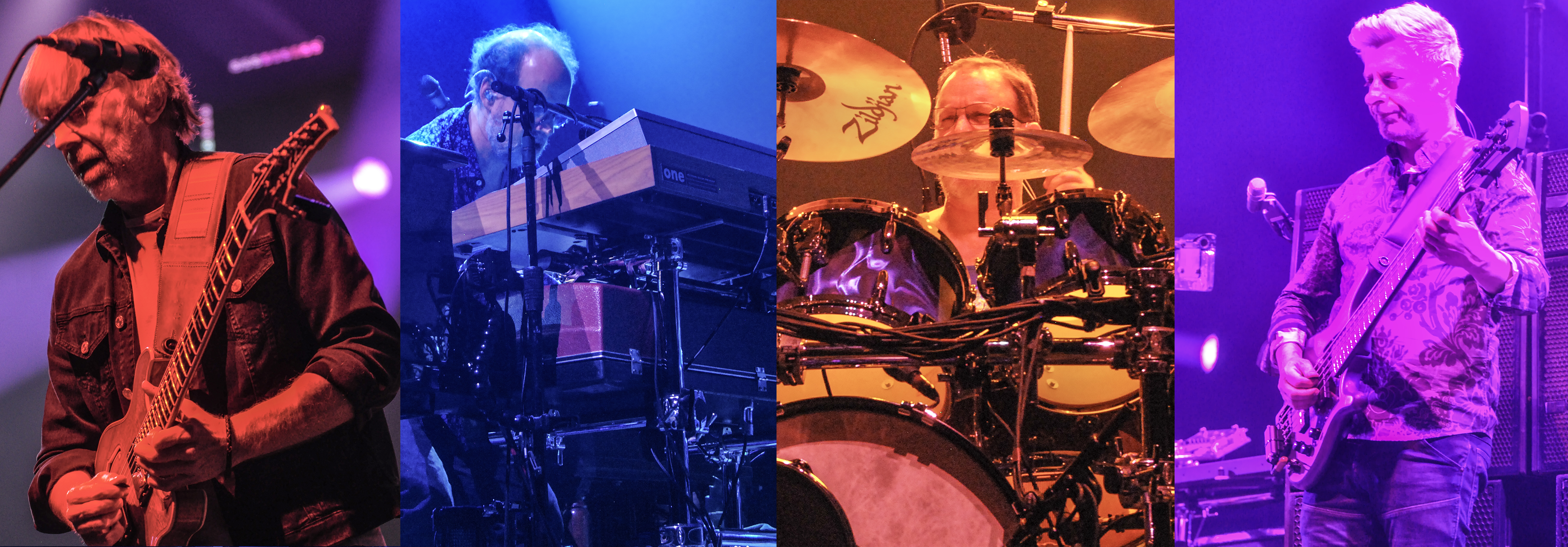

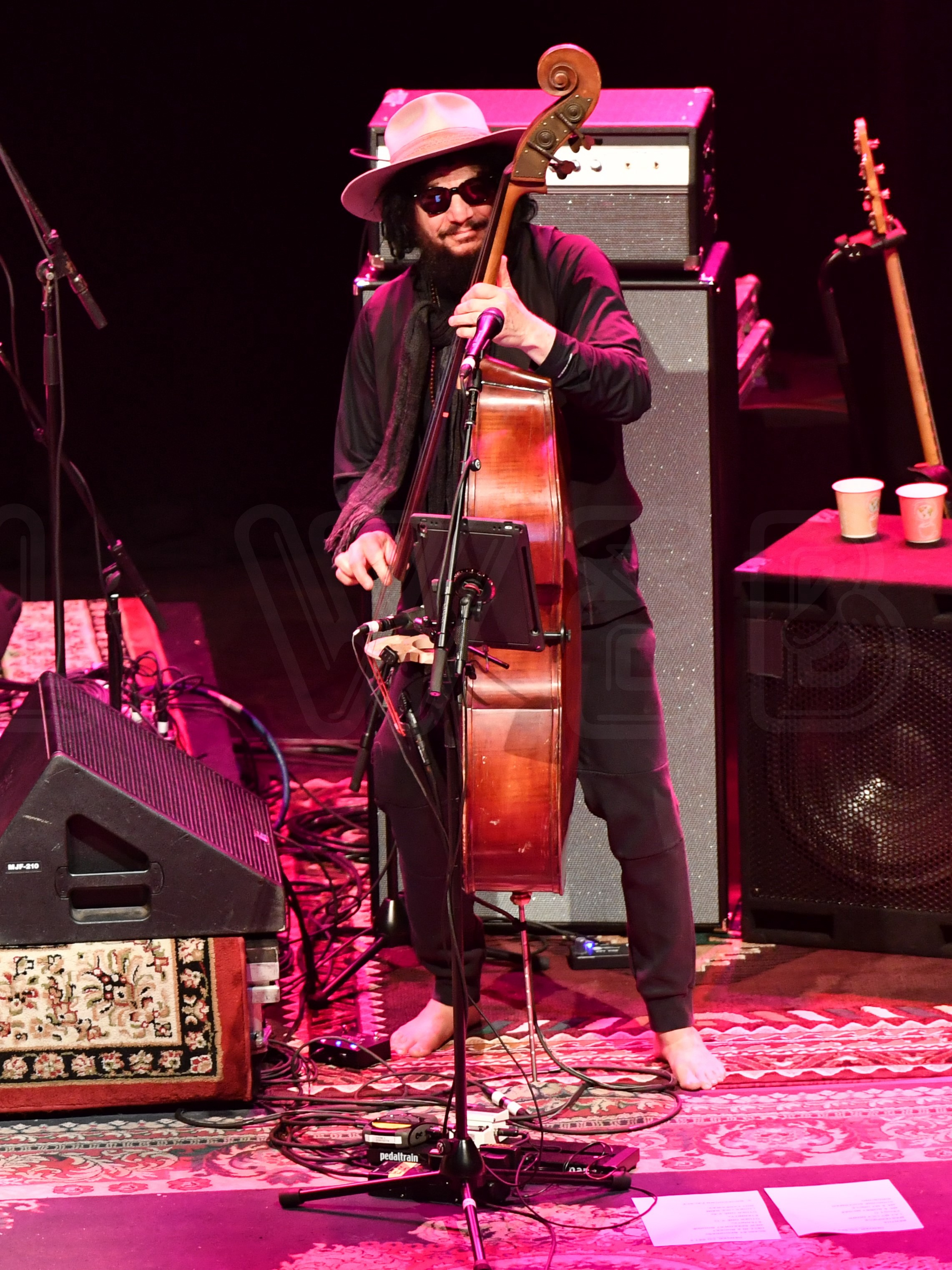

And, of course, if you stick around for the whole interview, you’ll see near the end that the jazz/rock/pop bassist also briefly tips the ever-expanding headband of his Spaghetti-Western trail hat to give us all a taste of what his new, nine-member touring band, The Pan-Detroit Ensemble, has in store on their upcoming spring tour. (Please see listing of tour dates, with a May 21 start date, at the end of this article.) Members - whom Was says all share his Detroit roots – include with saxophonist Dave McMurray, keyboardist Louis Resto, trombonist Vincent Chandler, trumpeter John Douglas, drummer Jeff Canaday, percussionist Mahindi Masai, guitarist Wayne Gerard and vocalist Steffanie Christi’an. And, of course, Was provides all of those thick bass grooves.

GW: I know this is a busy period for you, Don, so we appreciate you being able to squeeze us in. As a music photographer myself, I think this photo exhibition is very exciting, especially because of all the legendary jazz artists represented. So I’d like to focus on your relationship with Blue Note and then have you talk about the creation of this show.

Don Was: Sure – Glad to do that.

GW: First, could you talk about Francis Wolff’s legacy as a co-founder of Blue Note and also as the label’s photographer?

Don Was: Well, he was a commercial photographer in Berlin. He and Alfred [Lion, founder of Blue Note] were old friends and they shared a love of black American music. So he had left Berlin – literally – on the last ship out of Germany that he could get on. And I think that with both of them being persecuted Jews, they heard something in that music they heard coming from persecuted black Americans that they could relate to. Something that was built into this music, certainly from its roots in Africa and how [the musicians used that] as a kind of ‘secret language’ to hang on to, to create a kind of forbidden culture. I think that’s what gives the music a kind of universal appeal, because people all over this world are oppressed in different ways. You can find something in those rhythms and those choices of notes that speaks to you about a yearning for freedom. All from music.

So Alfred came over and started this company and Francis joined him soon after that. And Francis took his camera everywhere. He went to every session over three decades, and to many live gigs. Shot constantly. And it’s this incredible historical archive of what occurred in this milieu over this period of time. But there was something more that he captured – I don’t know whether it was intentional or not – but it was the atmosphere.

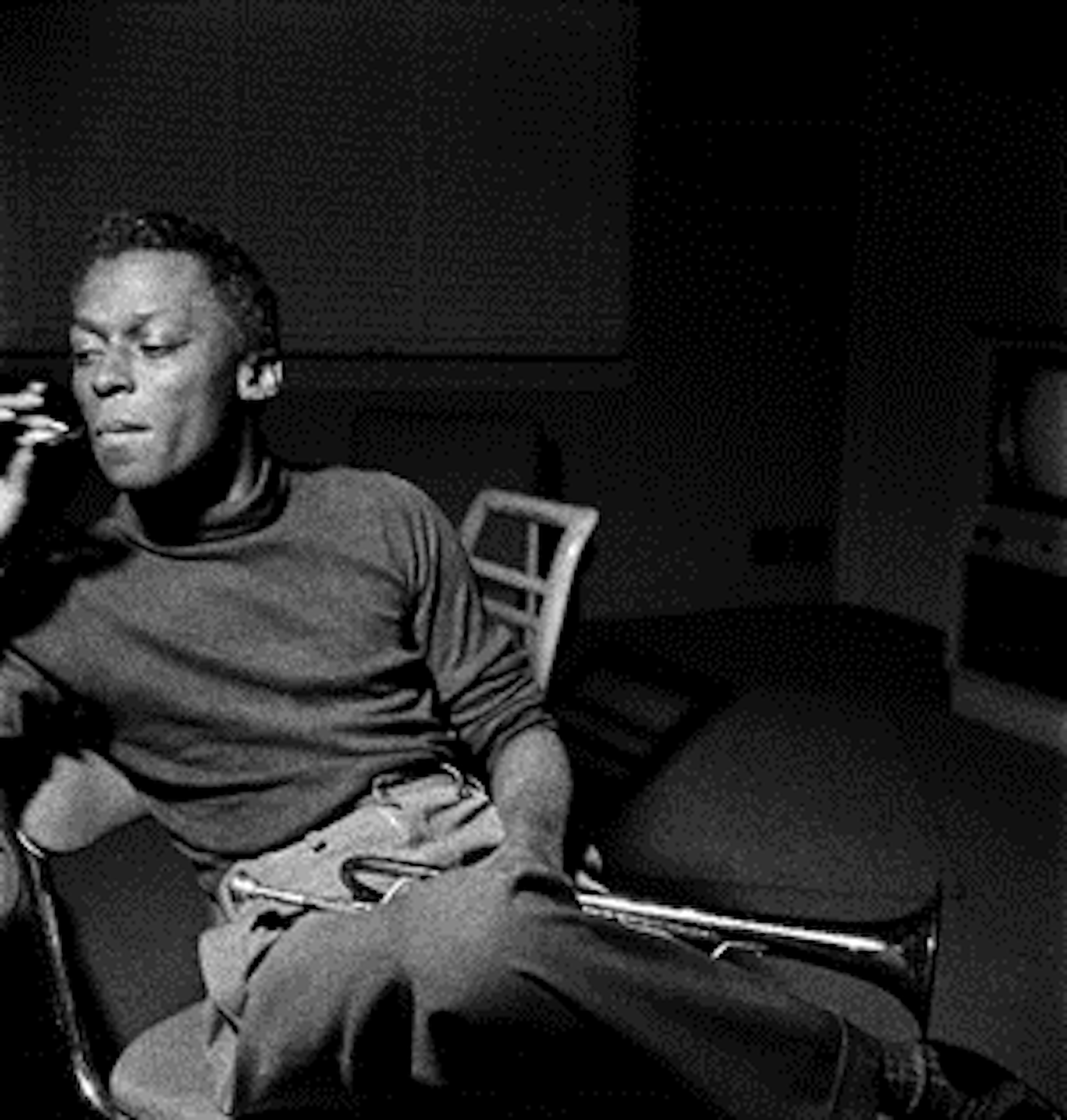

I discovered jazz and Blue Note records in 1966. The graphics and the photos expressed something about this dark, mysterious world to me. I’d flip the album covers over [in record stores] and see these incredible black-and-white photos. You couldn’t tell what kind of rooms these guys were in. The walls were black. There was cigarette smoke. And these guys were holding saxophones and wearing the coolest clothes.

I was only 14, but all I knew was that those photos made all that look like the coolest place in the world. And I wanted to part of it! So Francis provided the visual counterpart to the music that Blue Note was recording and releasing. It’s got some special magic to it!

GW: That’s amazing. I’m curious, with so many images to review – I read that it was something like 20,000 – what was the planning time like for this exhibition and how many people worked on it?

Don Was: We [Blue Note] didn’t own the archive. Francis got sick in the early ‘70s. [He passed away in 1971.] He took all of his photos, put them in a trunk and sent them to Alfred, who was living in San Diego after he retired from the music business. Francis did that because he didn’t want people abusing the archive. And Alfred kept them until he passed away in the ‘80s.

And then a guy named Michael Cuscuna is the person who had really resuscitated all of our tapes. (Cuscuna was the discographer who oversaw the re-release of Blue Note’s classic albums from 1985 to 2007.) They were just sitting in boxes, unlabeled. We didn’t really know everything that we had. (Some sessions or full collections had never been released, such as The Complete Blue Note Recordings of Thelonious Monk , which Cuscuna curated and released in 1994.)

So Michael went through and listened to everything, catalogued all of it. Figured out who all of the musicians were on the sessions, and really saved them for posterity. And he did the same thing for the photos. He became the caretaker of those and maintained the negatives for a long time. So we recently purchased them back and did a couple of years of digital rescanning of all those negatives.

This exhibition is the first one of this kind that we’ve put on. And it’s also the first time that the prints are coming from these scans, so they have a much higher resolution than the prints we had previously. No one’s seen these photos the way they look now – I’ve seen some of them, and they’re awesome. They really capture the feeling of that musical energy.

GW: Are there any side-by-side ‘before and after’ photos in the show that make that comparison?

Don Was: No – heh-heh – that’s a really good idea, but we didn’t think of that.

GW: That’s so interesting. I definitely wanted to know more about the preservation and restoration of images, so you’ve answered that for me. I’m curious whether Francis was the sole photographer or if he had other people covering performances when he couldn’t attend a particular show.

Don Was: That’s a good question. Not really sure, not to any great extent, I think. By the end of the ‘60s, he wasn’t shooting so much anymore, and the images on the albums began to change. They used more models and a lot more professional, commercial photography was used then. It was still cool but I think it lacked the soul of Francis’ photos.

GW: So I assume that the exhibition doesn’t include any other images from those later album covers, just Francis’ images, right?

Don Was: Yes, exactly. And it’s nice because, outside of a couple of books that have been published over the years, this is the first time that his photos are getting this kind of treatment. The images are independent of the album covers on which they appeared.

GW: The photos as fine art. . .

Don Was: Right. The photos finally get recognition and are presented as art in themselves.

GW: How much of the curation was done by the FARHOF team and what was your role in it?

Don Was: We did it totally ourselves. We did most of it around the time of the 85th anniversary of Blue Note [this year, on Jan 6, 2024]. Heh – I was in the ‘Blue Note Spirit’. We knew we had some choices to make, things were looming over us. We jumped into it and pretty much had all the photos for the show chosen within a couple of days. It was a lot of work, and, now, I can’t tell you that we studied every one of the 20,000 images, but we looked at a lot of them and made decisions [on the fly]. Some have never been seen before, and others are iconic and very well known.

GW: Could you tell us more about the presentation in the show – the sizes of printed photos, framing and so on?

Don Was: Well, honestly, I’m not the exhibition curator and don’t know how they will be presented, although I pretty much chose the photos that are on the wall. But the folks at FARHOF have been handling all of [the mounting of the show]. I’m really just as eager to see it as you are!

GW: Fair enough. . .

Don Was: We discussed a lot of the plans but didn’t work through all of that with them. But, to be sure, it was a labor of love for me. It wasn’t like, “Awww, maaan. . .how many more of these photos do we have to look at?” No. . .it was fun! Y’know, it’s part of the reason that I took the job. I spent most of my life avoiding having a job. That was my goal! I never thought of playing music or making records as ‘being a job’. And I made it to age 58 and this gig [at Blue Note] was offered to me – which proved irresistible. But the lure of it was, “Man, now I’m going to get to listen to all of these tapes and see all of these photos, in their original boxes. . .”

GW: So when you became Blue Note president in 2012, you had started a bit before doing A&R (artist & repertoire) work for the label. Did you have any exhibitions like this in mind at that stage, or did that come only after you were on board for a while?

Don Was: Well, we didn’t own any of the photos at the time. Michael owned them, and it wasn’t ours to do. We could encourage him to do things, and we worked with him on different ideas. It took us a couple of years to talk him into parting with the negatives. I think that I actually didn’t know what I was getting into! Yeah, that’s a fair statement! I thought [the job] was going to be all listening to music and looking at pictures.

GW: How much do you know about Francis’ working methods? For example, I know he used a handheld Rolleiflex [medium-format] camera. Seems that was very flexible and gave him a lot of freedom.

Don Was: Yes, he used a Rolleiflex – and he had a flash. During rehearsals and warm-ups, he’d get his images. Not during an actual take, so he wasn’t running around in the studio as actual recording began. No flash or clicking sounds that would get on to the recordings. He’d capture a lot of great moments of discussions before the session, y’know, the exchanges between the musicians. It really puts you in the room more, and you get these insight about these iconic legends at work on their recordings.

GW: So did Francis do all of his work for Blue Note or did he seek or welcome assignments from publications or from non-Blue Note artists?

Don Was: He was one of the founders of the company, and I think he understood that his photo work for the label gave Blue Note a competitive edge and he was focused on just doing that work. Y’know, if a magazine like Downbeat was planning a story on a Blue Note artist, such as Herbie Hancock, they might have made a call to see what photos Francis might be able to provide. But, no, I don’t think he did photos for them specifically.

GW: In terms of FARHOF, what is your connection with that organization?

Don Was: I’m a member of their artist advisory board. As a musician, I’ve also played there a number of times with [Bob] Weir, in both of the [Boch Center] theaters – the Shubert and Wang Hall. Those are special rooms – always love going in there [to perform]. And I became friends with Joe Spaulding (former CEO and president of the Boch Center), and he showed me what he was doing with the Hall of Fame. I think that’s essential to have a separate museum and hall of fame for that kind of music that’s so important and, really, so under-appreciated.

GW: Have you worked on any other exhibitions with them, or was Blue Note the only place where you overlapped with them?

Don Was: Well, the museum’s still in its early stages. I was in Boston at a board meeting and we (Blue Note) had just purchased Francis’ photo archive. So FARHOF had done a couple of things, like an Arlo Guthrie retrospective, and they were just thinking about what they could do next. And I said, “Well, we could do something like this.” And they said, “That’s something [a retrospective of those jazz artists] that’s never been done.” And it just all worked out. It was, y-know, Kismet!

GW: So many of the featured artists are no longer with us, and that makes an exhibition like this all the more poignant and insightful. When you have the exhibition opening, would any of the living legacy artists be able to attend?

Don Was: No, not any of those folks specifically. The museum itself will be having an induction event at the same time, their first one in fact, and it will be timed with the opening. A whole lot of other artists who are being honored by FARHOF will be there. There aren’t many [of that original generation of jazz] artists left. For example, there’s still [jazz bassist] Ron Carter, who maybe will make it in at some point.

GW: On your own musical front – if you’d have time to talk about it – is there anything you’d want readers to know about the upcoming Pan-Detroit Ensemble tour?

Don Was: Ohh, them? Oh, yeah – heh-heh – I’d be happy talk about that. Y’know, one of the things I discovered from playing with Bobby [Weir] is that all the conversations among the musicians are so important. And then, y’know, when we perform, the audience becomes a part of those conversations. Getting that interplay between the band and the audience is the thing that is so addictive about playing with Bobby. That makes it such an incredible experience for the audience, because, the Grateful Dead audience is the best audience I’ve ever been exposed to from the stage. It’s really special what goes on with them.

So, y’know, I thought: “How can I apply this to a conversation that reflects my roots, where I come from?” So that’s Detroit, and there’s this thing that happens there – it’s really interesting that goes all the way back to the post-War [WWII] period. All these people [from different regions] just flocked to Detroit for jobs, and they brought all their personal experiences, and their disparate cultures with them. And all of these different cultures are reflected in the music.

So people of my age, we all grew up in the thick of this really rich jambalaya of musical flavors. And the [merging] of all that brings all those influences together in a really unique way. So I just thought: “Hey, just go back to Detroit and play with other musicians who grew up listening to the same stuff as you did. And just take that unique sound – it’s jazzy, it’s R&B, blues and it’s rock ’n’ roll.” But, y’know, you look at Blue Note history and you’ll find there are more musicians on the label who are from Detroit than nearly any other city, by far. There’s always been lots of great stuff going on here and I got to grow up in the middle of it. I got to see great folks like Yusef Lateef, Donald Byrd and Joe Henderson playing live gigs here.

So, yeah, I’ve been wanting to put all those things together, and, y’know, when I was in Was (Not Was), we hinted at some of that, years ago. . .

GW: I can hear that!

GW: So, yeah: “How can we take that further?” In Was (Not Was), we never really got to stretch out. We were more focused on making pop albums, only slightly drew on those influences. But I asked myself, “What would happen if we’d stretch out, more like the Dead do?” I’ve been working on it for a couple of years, hearing the sound I want in my head, but we finally got it last October. I had a group of musicians in the room together and we hit that conversation that blows the roof off the place. So I knew right then: “OK, you’ve finally got what you’ve been looking for. Don’t walk away from it!”

GW: So this is going to just be a short debut tour in a few weeks?

GW: Yes, this is going to be our first tour, doing [a handful of dates], from the end of May and into early June. It’s always fun doing those first couple of shows, because – heh – nobody knows exactly what is going to happen. And yet, everyone’s paying attention and we’re shaping something together that there’s no pattern or mold for yet. So this is going to be a special tour, because we’re playing a wide range of venues, from jazz rooms to the [three-day festival] DelFest, and a couple of benefits like the Rex Foundation benefit in Ardmore PA. (Unlimited Devotion: A Rex Foundation Benefit & Grateful Dead Celebration). And then, we’ve got symphony venues, like the Detroit Orchestra’s hall, where our show is going to be part of a music series, right there in our home town.

GW: That’s great, Don. So I really just have one more question and that’s about what kinds of material the audience might expect. Originals, covers, jazz or rock improv, or even all of that, all mixed up? And the same songs each show maybe done differently, or more open-ended from night to night?

GW: I do have an initial set planned and we’ll just see where it goes from there. I don’t know that it would change that much, but I do know that we have more than a 90 minute show. Obviously, some jazz covers – something by Yusef Lateef, and Olu Dara, for example. Very likely a couple of Dead songs, maybe something from one of my bands I had for a while called Orquestra Was that had [trumpeter/pianist]Terence Blanchard and [pianist] Herbie Hancock playing with me. I’d like to do something from that album. Maybe a movie score thing I did with Terence and Dave McMurray, and even a couple of Was (Not Was) songs. Probably not “Walk the Dinosaur”, y’know, but a couple of fun songs I know audiences would like.

GW: That’s great. Guess it’s too much of a long shot for “I Feel Better than James Brown”?

Don Was: Wow! Hah-hah! That’s one of them, man. That, plus “I Blew Up the United States: and “Wheel Me Out”. So, yeah – there’s three Was (Not Was) songs, right there!

GW: I’m glad the Ensemble’s coming to Cincinnati, Don. Will be looking forward to it!

Don Was: It’s definitely going to be all kinds of different things, and I’m really excited to see how audiences like us.

Don Was & The Pan-Detroit Ensemble Tour Dates:

May 21 – Dakota – Minneapolis, MN

May 22 – SPACE – Evanston, IL.

May 24 – Orchestra Hall – Detroit, MI

May 25 – Memorial Hall – Cincinnati, OH

May 26 – DelFest – Cumberland, MD (Annual three-day music festival, hosted by American bluegrass legend, Del McCoury.)

May 28 – The Vogel at Count Basie Center – Red Bank, NJ

May 30 – The Hamilton Live – Washington, D.C.

May 31 – City Winery – New York City

June 2 – Unlimited Devotion: A Rex Foundation Benefit & Grateful Dead Celebration – Ardmore Music Hall – Ardmore, PA