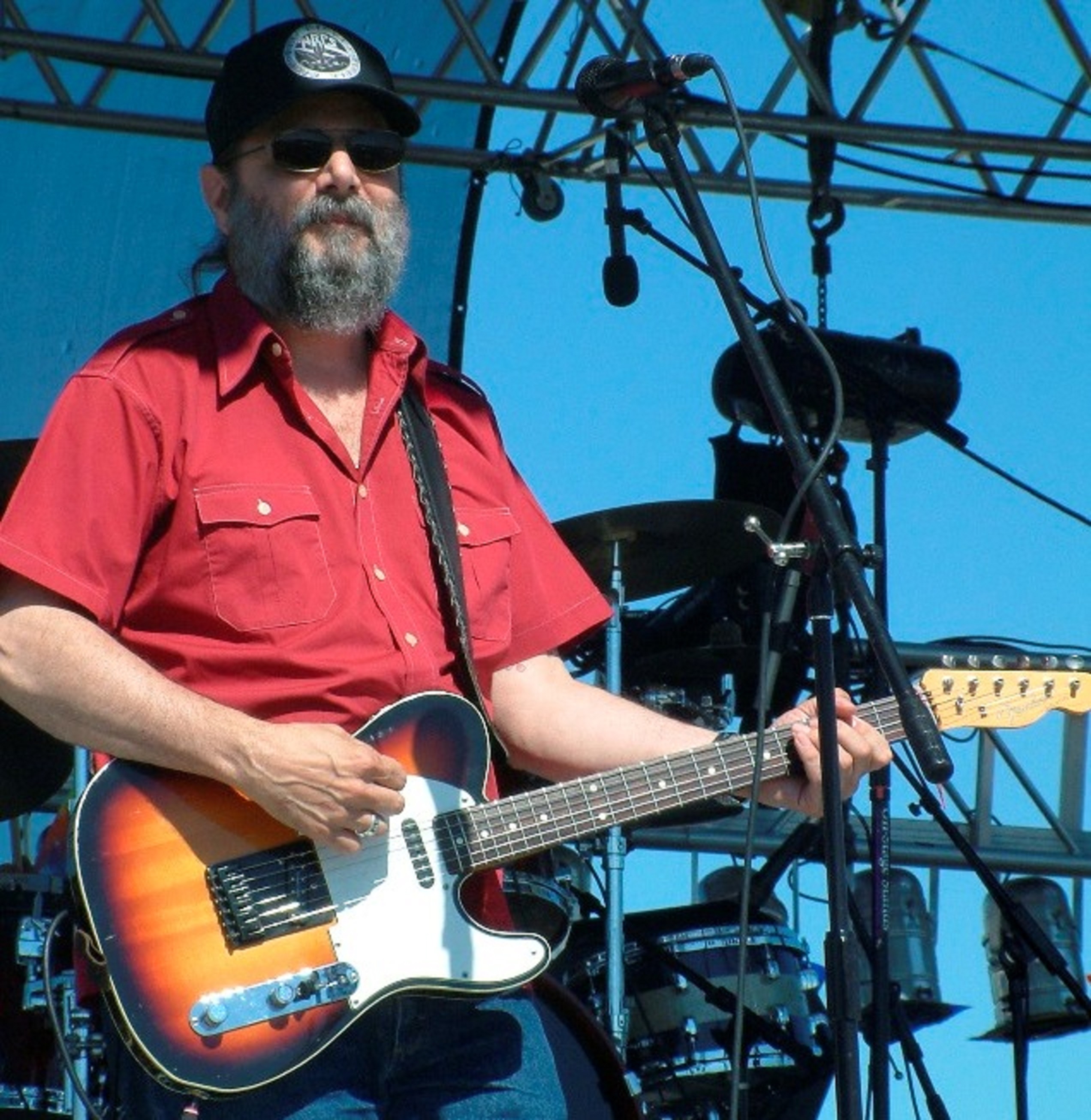

GW: This is Dylan Muhlberg of Grateful Web here with Tim O'Brien who is widely acknowledged as a master songwriter and virtuoso multi-instrumentalist. His groundbreaking style fuses various elements of Country, Blues, Bluegrass, and Folk, while remaining progressive in character. Mr. O’Brien co-founded the Colorado Bluegrass institution Hot Rize back in the late 1970s, and additionally has built an exciting solo career including endless collaborations with other legends of the Country and Bluegrass world. Thanks so much for joining us this morning Tim.

TO’B: Great to be with you. Thanks.

GW: Likewise. Your music continues to reveal important root qualities of country and folk music. At the same time your compositions and songwriting reflect a playful progressive nature. Is it a challenge achieving this balance?

TO’B: I maybe have achieved the balance in spite of myself. I try to make things understandable. And I’m also so rooted in tradition that stuff will sound reminiscent even if it’s a modern subject. It’s an interesting process trying to be a traditional musician and stay creative. You can sometimes get bogged down on not trying to copy people. You just gotta’ be yourself.

GW: Speaking of which, (Lester) Flatt, (Earl) Scruggs and (Bill) Monroe were considered genre-benders when they pioneered the bluegrass sound. Do you feel that there’s a line to be drawn with contemporary bands that further fuse outside elements or is there a place for some evolution in instrumentation?

TO’B: We’ll you know its gonna happen regardless of what anyone protests about. Music keeps evolving. It evolves because our culture evolves and because technology evolves. Different things are possible; suddenly people start thinking in new ways. What’s interesting the big themes just keep coming back. I feel that the music is always safe there’s no reason to be worried about it because the basic elements still come back and they become valuable at the end when they’re ignored for too long. That’s why you have people like Del McCoury who are setting the woods on fire here in the traditional bluegrass world. Fans, young and old are latching on to that incredible power of the traditional sounds. And it has to evolve and that’s why we’ve got acts like the Punch Brothers. Where it’s just classical and jazz becoming all related; it always has been interrelated. They’re just showing new paths to that. Bill Monroe was certainly a radical in his day. He was combining jazzy elements to the tradition that he grew up with in Kentucky. The old ballads and fiddle tunes that his mom played and sang, and the blues that he learned from Arnold Shultz. He went to Chicago and heard Dixieland Jazz and he thought “Wow. Maybe I can add some of this together and play it on a mandolin and it would be my music.” Now we have everybody doing the same thing [trying to make their own music]. It keeps evolving and it’s a natural thing. Everything is safe. Everything is always changing.

GW: Sure. You grew up in West Virgina, became a legend in Colorado, and completed the journey by moving to Nashville in the 90s. How have all these changing surroundings influenced your style?

TO’B: Well Colorado was good. I moved to a college town and there were a lot of kids striving to learn music. The clubs were happening. It was an age where I had the energy to go out and hear music whenever I could. It was a lot of activity; people of a certain age group were collaborating. And of course the mountain culture there. Colorado is a place where people go for a better life. They love the weather. They want to go skiing and rock climbing, river rafting, hiking. Maybe they just like the sunny weather and clear air. So it breeds an open-minded person whose coming there for a different kind of life. I got to hear so much strong music in Colorado. It was a nurturing environment. And then of course, moving to Nashville you get a sense that makes you feel like your going around the track really fast. Things are faster and people are making more deals. Folks are more finely tuned as musicians because you have to be to compete. That competition there helps you hold your ground. You’ve got to keep up with people. Commercialism and the trends can also bog you down. But by following the trends you’re automatically behind. That can be a trap there. Everyone is trying to get the next country radio hit. If you imitate what the hit was last week you’re probably not going to make that happen.

GW: I always think that the [Robert] Altman film still rings true today.

TO’B: [Laughs] it does.

GW: So your music is often described as being “Americana” or “Roots.” I’ve seen you collaborate brilliantly with non-American artists such as Irish Fiddler Kevin Burke. Do you feel limited by the labeling of “Americana”?

TO’B: No, I don’t feel limited by it at all. That label is just a grab bag of many things that had to do with America. And guess what, plenty of Irish Immigrants over the years have made up part of Americana. We had a huge slave population and race war. So many elements play into it. It includes music from Europe and Asia. Bluegrass can be limiting. That label can mean that you can’t have electric guitar or drums; you can’t have electric bass even. You shouldn’t even plug it in. If you want to you can look at it that way. That can be limiting. But Americana man that’s all over the map. It’s a giant genre.

GW: You have a new album out with old friend and collaborator Darrell Scott. “Memories and Moments” is a gorgeous bare-bones musical revival with mostly originals, and a few covers. Many of the tracks sound decades old, as if they were old-time tunes taken from the folk cannon. How did the two of you manage to create these fresh tracks with such sincere nostalgia?

TO’B: I just think that Darrell Scott is got deep roots. He’s touched in and it reaches down to almost the center of the Earth or something. He’s got a mysterious and uncanny sense of music and lyrics, wordplay, and metaphor. Again it’s just that most of us are trying to get at the real thing musically and lyrically. Hank Williams and Bill Monroe as well as George Jones songs made it on there. We do a song along with John Prine. Those are three steps on the tradition. Starting with Hank, then George Jones, then John. Our songs are our own songs but they’re definitely tempered by those influences. Also I think that when you take away a lot of instruments and just have two instruments and two voices you get a much more up-close perception of the music as opposed to a big production. You don’t have a polished sheen to things. You’re just dealing with more basic elements. I’ve found from doing duets with my sister Mollie that when there’s a two-part, not a three-part song that people feel welcome to sing along in their car or their houses or wherever they’re singing the music. Without a whole band there they feel comfortable with it. I think that’s a key way we use to get closer to people.

GW: Listening to “Memories and Moments” all of the track evoke those feelings. Scott and yourself will continue your musical brotherhood in support of this release starting this September in Nashville. It’s been a while since the two of you toured together exclusively. Do you expect that there will be a learning curve, reacquainting to each other’s current musical self?

TO’B: Yeah. They’ll be a little bit. But it’s always been real comfortable whenever we play. We played at the end of last May at a Festival. That was a first time in a while other than a little recording. We were there and Darrell was actually kind of nervous before the show asking what songs we knew. And we started making this list that got to be a little long. We played a few of those. Then we got onstage and ended up playing quite a few that weren’t on it. It’s not like rocket science for us. He’ll play a song. And if I don’t know the song I’ll listen until I can do something that compliments it. And he’s the same way. He listens and responds so quickly that it’s almost like you never had to learn it. There’s that complimenting from the get-go. Part of the thing that we aim for is to get that something new and play it differently when we played it before. In a way we want there to be some sort of sand in there makes the Oyster. He’ll consciously mess it up to make it seem a different way. He’ll change his voice in the middle of a sing, from a whisper to a roar. It’s really inspiring to be on stage or in the studio next to him.

GW: Wonderful. I know fans are absolutely thrilled for the revival of the collaboration including myself. Let’s talk about Hot Rize for a minute. Over a decade ago after the untimely passing of Hot Rize co-founder Charles Sawtelle, the legendary outfit continued to perform and has continued more and more frequently with Nashville flat-picker Bryan Sutton. Why was it important to you, Nick [Forster], and Pete [Wernick] to continue performing as and revive Hot Rize?

TO’B: Hot Rize was for twelve years our full-time career. It started in 78’ and went until the spring of 1990. So we had twelve years of collaboration and we’re kind of growing up as musicians during that time. Pete Wernick and Charles Sawtelle certainly had more experience that Nick and I, both performing and recording. We all kind of were learning together. So a dozen years later we continued playing. I felt the need to eventually do my own thing and branch out into a solo career. But it was too hard to let it go. It was too much a part of who each of us are. It wasn’t like we had a big argument and quit. It my mind it had gone as far as it could go at the time. I needed a change. The change was starting to happen but I didn’t want to say goodbye to those guys. And as the years went on it became like a great family reunion. We’d do a couple of shows. Now we’re in the process of making a new recording. That has also been a long-time coming. It’s necessary for the same reason. As musicians we’ve grown separately and now we can come together and do some other things. What we started with was promising and I think it’s going to be a good recording. It brings back that sound of the four of us. Bryan has been with us for ten years now. He’s not the new guy so much anymore. It’s time to own up since we have the band and do new shows. After Darrell Scott and I have done our traveling for a year we won’t go on full time but will do quite a few more shows with Hot Rize.

GW: One more question for you Tim. Does humor belong in bluegrass music?

TO’B: [Laughs]. We’ll humor has always been there. I was reading some stuff about Bill Monroe in the early days. I guess he had worked up comedy routines and actually dressed in drag in those early shows, before the Opry [Laughs]. These were in the days of Vaudeville and Minstrel Shows. And Black face. They may have done some of that stuff. He would sing songs like children’s songs such as “Shady Grove,” just clever little ditties to add a little humor. He was a serious man but I think he believed in poking fun at himself. With humor in bluegrass gets a little bit too serious sometimes and I think it helps. Stanley Brothers used to do the old Arkansas Traveler Routine where one guy is lost and asks directions from the other guy. He’s lost in the country trying to find his way to Little Rock and he asks the other guy “How deep is this mud puddle?” And the guys says “We’ll I reckon it goes all the way to the bottom…” Then he asks, “Does this road go to Little Rock?” And the guy answers, “No it stays right here.” So it was like a City Slicker is trying to make fun of the Country Guy is an enduring theme in Bluegrass Music. There’s that dichotomy. And Hot Rize always tried to make good, strong music but we always tried to poke fun at ourselves. So when the music started we’d be play seriously. Even when Red Knuckles comes out we’d still try to play it well. It helps to reveal that you’re not perfect. Poke fun at yourself. Humor gets everybody in the audience on the same page. You’re all sharing the same thing. You’ll all laugh. Laughing at ourselves. Everyone realizes that we’re all equals. I think humor is very valuable.

GW: Tim I really wanted to thank you for your time. I’ve been seeing Hot Rize in Colorado as long as I’ve been able to. I really want to encourage our listeners and readers to check you out at the RockyGrass Festival with the Lomax Project and your own Tim O’Brien Band. Also listen to the new release with Darrell Scott and try to catch them on the road starting this September.

TO’B: There are a couple more things I’m doing at RockyGrass. I’m playing with Andy Statman whose an incredibly innovative player from New York. I was privileged to play on his recording that is coming out soon. He adds some formalities from progressive jazz and bluegrass music to his sound. R&B. That’s exciting. And then there’s this thing on Saturday night that Jerry Douglas invited me to do called “The Earls of Leicester,” which is a play on Flatt and Scruggs. Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and their Foggy Mountain Boys. We’re doing the repertoire of the Foggy Mountain Boys as our performance. We have instrumentalists and singers that can really cut this stuff. Jerry has brought together and organized all of this. Charlie Fishman is a great Earl Scruggs purveyor. Shawn Camp is playing the part of Lester Flatt. I’m playing the part of tenor singer and mando player Curly Seckler. We have a fiddler Johnny Warren who’s Dad was Flatt and Scruggs fiddle player for twelve years. Johnny plays exactly like his father. It’s very exciting to play the traditional stuff and to get with Jerry and then get pretty progressive with Andy all in the same weekend. It’s really all over the spectrum. All the way from the Alan Lomax field recordings to that classic Bluegrass sound. It’s quite a weekend.

GW: I can’t wait. Thanks so much for revealing details about Saturday Night RockyGrass’ headliner slot. Thrilled to hear to you’re a part of it.

TO’B: Thank you Dylan, take care.